LSD

| Summary sheet: LSD |

| LSD | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Nomenclature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common names | LSD, LSD-25, Lucy, L, Acid, Cid, Tabs, Blotter | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Substitutive name | d-Lysergic acid diethylamide | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systematic name | (6aR,9R)-N,N-Diethyl-7-methyl-4,6,6a,7,8,9-hexahydroindolo-[4,3-fg]quinoline-9-carboxamide | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Class Membership | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Psychoactive class | Psychedelic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chemical class | Lysergamide | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Routes of Administration | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interactions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cannabis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stimulants | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tramadol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deliriants | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tricyclic antidepressants | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ritonavir | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lithium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lysergic acid diethylamide (also known as Lysergide, LSD-25, LSD, L, Lucy, and Acid) is a classical psychedelic substance of the lysergamide class.[2] It is perhaps the most researched and culturally influential psychedelic substance, as well as the prototypal lysergamide. The mechanism of action is not fully known, although serotonin binding activity is thought to be involved.

The psychoactive effects of LSD were first discovered in 1943 by Albert Hofmann at Sandoz Laboratories (Switzerland).[3] In the 1950s, it was widely distributed by Sandoz as an experimental drug for psychotherapy and scientific research;[4] during this era, it provoked considerable interest from the intellectual establishment and was even the subject of a clandestine investigation by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for potential applications in "mind control".[5]

Recreational LSD use became a central, highly-visible aspect of the 1960s youth counterculture movement, eventually paving the way for international prohibition in 1971.[6][7] Today, illicit recreational use remains widespread and it is associated in popular culture with the counterculture and rave scenes. The lifetime prevalence of LSD use among American adults is 6-8%.[8]

Following decades of institutional suppression, scientific research involving LSD has recently undergone a massive revival.[4] As a part of the so-called "psychedelic renaissance",[9] it is currently being investigated in the treatment of a number of conditions including alcoholism,[10] substance addiction,[11] cluster headache,[12] autism,[13] and anxiety associated with terminal illness.[14]

Subjective effects include visual geometry / hallucinatory states, time distortion, enhanced introspection, conceptual thinking, increased music appreciation, euphoria, and ego loss. LSD use is reportedly associated with mystical-type experiences that are sometimes claimed to facilitate self-reflection and personal growth.[15] It has been called the first modern entheogen, a group which is otherwise limited to traditional plant preparations or extracts.[16]

Unlike most highly prohibited substances, LSD has not been proven to be physiologically toxic or addictive.[2][17] However, adverse psychological reactions such as severe anxiety, paranoia, delusions, and psychosis are always possible, particularly for those predisposed to mental disorders (see this section).[18]

It is highly advised to use harm reduction practices if using this substance.

History and culture

The original synthesis of LSD was recorded on November 16, 1938, by the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann while employed at the Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland.[19] The compound was synthesized as part of a large research program searching for medically useful derivatives of ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and other grains.

However, it was not discovered to be psychoactive until five years later, when Hofmann claimed to have accidentally ingested an unknown quantity of the chemical before proceeding to ride his bike home.[19]

The first intentional ingestion was recorded on April 19, 1943.[20] Hofmann ingested 250 micrograms (µg) of LSD, believing it would be a threshold dose based on the doses of other ergot alkaloids. He found the effects to be much stronger than he anticipated and was impressed by its profound mind-altering effects. April 19th is now celebrated annually as "Bicycle Day".

In 1947, Sandoz introduced LSD to the medical community under the name Delysid, marketing it as an experimental tool to induce temporary psychotic-like states in normals (“model-psychosis”) and later to enhance psychotherapeutic treatments (“psycholytic” or “psychedelic” therapy).[20] The substance had a major impact upon its release — within 15 years, research on LSD and other hallucinogens generated over 1,000 scientific papers and was prescribed to over 40,000 patients.[21]

In the 1950s, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) created a research program code-named MK-ULTRA that would conduct clandestine research investigating LSD for applications in 'mind control' and chemical warfare. Experiments included administering the substance to CIA employees, military personnel, doctors, prostitutes, mentally ill patients, and members of the general public without their knowledge or consent, which resulted in at least one death.[5]

In 1963, the Sandoz patents for LSD expired. Several prominent intellectuals, including Aldous Huxley, Timothy Leary, Al Hubbard, and Alan Watts began to advocate for the mass consumption of LSD; according to L. R. Veysey, they profoundly influenced the thinking of the new generation of youth.[22] LSD became a central, highly-visible feature of the youth-driven counterculture of the 1960s, provoking widespread controversy and backlash in American civil society.

On October 24, 1968, LSD possession was made illegal in the United States.[23] The last FDA approved study in patients ended in 1980, while a study in healthy volunteers was made in the late 1980s. Legally approved and regulated psychiatric use of LSD continued in Switzerland until 1993.[24]

Names

The name LSD comes from its early research code name LSD-25, an abbreviation for the German spelling "Lysergsäure-diethylamid" followed by a sequential number.[20]

LSD has numerous street names including: acid, lucy, L, cid or sid. Also called blotter or tabs, a reference to their standard form of distribution.

Chemistry

LSD, or d-lysergic acid diethylamide, belongs to a class of synthetic organic compounds called lysergamides (a subclass of ergolines).

It is the "parent compound" of the lysergamide family, meaning it serves as the prototype for a series of compounds that are derived from its structure and have broadly similar effects. These include: 1B-LSD, 1P-LSD, 1V-LSD, ALD-52, AL-LAD, ETH-LAD, PRO-LAD, LSM-775, LSZ, and MiPLA.

The chemical structure consists of a bicyclic hexahydroindole ring fused to a bicyclic quinoline group (lysergic acid). At carbon 8 of the quinoline an N,N-diethyl carboxamide is bound. It is additionally substituted at carbon 6 with a methyl group.

It is a chiral compound with two stereocenters at R5 and R8. The active form of LSD is called (+)-D-LSD, which has an absolute configuration of (5R, 8R). The other three stereoisomers do not have psychoactive properties.[25]

The pure form occurs as colorless, odorless, prismatic crystals.[26] It is sensitive to oxygen, ultraviolet light, and chlorine (especially in solution).[25] Its potency may last for years if it is stored away from light and moisture at cold temperatures around 0°C or below, but slowly degrades at normal room temperature (25°C).[27]

Pharmacology

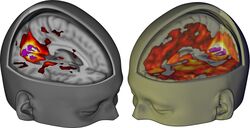

The magnitude of this effect correlates with participants’ reports of complex, dreamlike visions.[28]

The lower the dissociation constant (Ki), the more strongly LSD binds to that receptor (i.e. with higher affinity). The horizontal line represents an approximate value for human plasma concentrations of LSD, and hence, receptor affinities that are above the line are unlikely to be involved in LSD's effect.

According to various studies, LSD acts as a partial agonist at most serotonin receptor subtypes, including the 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C and 5-HT6 receptors, with high affinities.[29] The 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors are excluded. 5-HT5B receptors, which have not been found in humans, also have a high affinity for LSD.[30]

The mechanism of LSD's psychedelic effects is thought to be agonist (binding) activity at the 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT1A receptor subtypes, with high affinities.[31][32][33][34] Further information about how altered serotonin signaling may lead to LSD's signature cascade of visual and cognitive effects is available here. It should be noted that the mechanism is not fully understood.

Recent research has also found that LSD activates different intracellular signaling cascades than endogenous serotonin even when bound to the same receptor sites.[35] Because intracellular signaling cascades influence gene expression, LSD-induced signaling events within cells may inappropriately alter gene expression, which in turn may lead to changes in neuronal state and subsequently cognition.[36]

These findings help explain why the behavioral effects can resemble paranoid schizophrenia in humans.

The study concludes that acute LSD usage increases expression of a small set of genes in the mammalian brain that are involved in a wide array of cellular functions implicated in synaptic plasticity, glutamatergic signaling, cytoskeletal architecture and perhaps communication between the synapse and nucleus.[36]

Additionally, studies have shown that LSD possesses binding efficacy at all dopamine and all norepinephrine receptors. Most serotonergic psychedelics are not significantly dopaminergic, so LSD is unique in this respect. In particular, LSD's agonist activity at the D2 receptor has been shown to contribute to its subjective effects.[37][38]

"Flashbacks"

The etiology of the "flashback" phenomenon appears to be varied. Some researchers such as Krebs and Johansen (2015[39]) attribute at least some of the cases to be related to Somatic Symptom Disorder, when people fixate on normal somatic experiences and perceptions that they weren't aware of before consuming the drug. Other researchers relate it to an associative reaction to a contextual cue akin to what people that have faced trauma or strongly emotional experiences face when receiving a triggering stimulus (Holland and Passie 2011[40]). There is no consensus on what are the risk factors but some researchers theorize that pre-existing psychopathologies may be a significant contributor (Abraham and Duffy 1996[41])

The prevalence of HPPD is difficult to estimate but appears to be very rare (Halpern et al 2016[42]), with estimates ranging from 1 in 20 users for the transitory and less serious type 1 HPPD, to 1 in 50.000 users for the more concerning type 2 HPPD.[43]

Contrary to rumors circulating the internet that LSD is stored in the spinal chord or other parts of your body long-term,[44] the pharmacological evidence (Passie et all 2008[45]) shows LSD has a short half-life of 175 minutes, undergoing enzymatic metabolism into more polar and therefore water-soluble compounds such as 2-oxo-3-hydroxy-LSD that are eliminated through the urine. No evidence of long term storage of LSD in the body exists.

Subjective effects

Compared to some other psychedelics such as psilocybin mushrooms, LSA, and ayahuasca, LSD is reported to be more stimulating and fast-paced in its physical and cognitive effects. The wide variety of effects observed may be attributed to its so-called "promiscuous" binding activity at a range of CNS receptors other than serotonin, such as dopamine and norepinephrine receptors.

In terms of subjective effects, LSD may be described as possessing the visual and mental content of psilocybin or DMT along with the "dopaminergic edge" of a classical stimulant such as amphetamine or methylphenidate. Consequently, LSD euphoria can be described as "medium forced", which is higher than tryptamines but not as high as some phenethylamine-based stimulants or entactogens.

Additionally, it is associated with slightly more cognitive side effects such as anxiety and paranoia compared to psilocybin or mescaline. Some users report they have a harsher comedown that can resemble that of a stimulant, perhaps owing to its long duration (10 hr+) and sensitivity to its dopaminergic properties.

Disclaimer: The effects listed below cite the Subjective Effect Index (SEI), an open research literature based on anecdotal user reports and the personal analyses of PsychonautWiki contributors. As a result, they should be viewed with a healthy degree of skepticism.

It is also worth noting that these effects will not necessarily occur in a predictable or reliable manner, although higher doses are more liable to induce the full spectrum of effects. Likewise, adverse effects become increasingly likely with higher doses and may include addiction, severe injury, or death ☠.

Physical effects

-

- Neurogenesis

- Stimulation - LSD is usually described as very energetic and stimulating without being forced. For example, it tends to encourage physical activities such as walking, climbing, or dancing.

In comparison, other common psychedelics such as psilocybin or LSA are generally sedating and sedentary.

- Spontaneous bodily sensations - The "body high" of LSD behaves as a euphoric, fast-moving, sharp and location specific or generalized tingling sensation. [lower-alpha 1]

- Physical euphoria - A unique form of physical euphoria may occur at certain points of the trip. However, it is limited and inconsistent compared to the effect of entactogens or opioids, and can just as easily manifest as physical discomfort without any apparent reason.

- Perception of bodily lightness - The stimulation and energy LSD produces can cause the user to feel as if they are moving weightlessly.

- Tactile enhancement - Feelings of enhanced tactile sensations are consistently present at moderate levels throughout most LSD trips.[lower-alpha 2]

- Changes in felt bodily form - This effect is often accompanied by a sense of warmth or unity and usually near the peak of the experience. Users can feel as if they are physically part of or conjoined with other objects.[lower-alpha 3]

- Pain relief - LSD can greatly reduce or distort the perception of pain. This is likely due to a variety of factors as the hallucinogenic effects mean that pain can be interpreted as a different sensation (i.e. a tickling sensation from a painful stimulus).

LSD also possesses potent anti-inflammatory properties that likely contribute to this effect.[note 2]

- Temperature regulation suppression[4] - LSD appears to cause the body to lose some of its ability to regulate its temperature. While usually harmless, users should be careful when taking LSD in conditions of extreme hot or cold.

- Increased bodily temperature[46] - Potentially dangerous states of overheating have been reported to occur in certain conditions, particularly with higher doses due to the fact that LSD raises body serotonin.[lower-alpha 4]

- Nausea - Mild nausea is occasionally reported on moderate to high doses and either passes after the user vomits or gradually fades by itself as the peak sets in.

- Bodily control enhancement

- Stamina enhancement - The user's stamina for physical activities may be enhanced. Some users have also reported using small doses to improve athletic performance. However, this effect is generally mild compared to the effect of stimulants.

- Appetite suppression - LSD can suppress appetite in a manner similar to (although not as strong as) stimulants, especially for fatty foods.[lower-alpha 5]

- Dehydration - Mild to moderate dehydration may occur. Not as extreme as with stimulants or opioids.

- Difficulty urinating

- Increased blood pressure[4] - Due to the vasoconstrictive properties of the substance, blood pressure is consequently raised.

- Increased heart rate[4]

- Increased perspiration

- Muscle contractions

- Muscle spasms

- Excessive yawning - Excessive yawning is frequently reported, especially during the come up phase.

- Pupil dilation[4] - Anisocoria, i.e. significant difference in pupil dilation grade between the two eyes, can also be present. In the context of hallucinogen usage, this phenomenon has been regarded as harmless.[citation needed]

- Increased salivation

- Seizure[47] - Very rare but can occur in those who are predisposed to them, particularly while in physically taxing conditions such as being dehydrated, undernourished, overheated, or fatigued.

- Teeth grinding - Mild to moderate. Not as intense as on MDMA.

- Vasoconstriction - Dose-dependent, but weaker compared to stimulants, 25x-NBOMe, or DOx. Some users report feeling cold, especially in the extremities.

Visual effects

-

Enhancements

- Visual acuity enhancement

- Colour enhancement - Compared to other psychedelics, this effect is often reported to be brighter and more "radiant" in character.

- Pattern recognition enhancement

- Magnification

- Frame rate enhancement

Distortions

- Drifting (melting, breathing, morphing and flowing) - Compared to other psychedelics, this effect can be described as highly detailed yet cartoon-like in its appearance. The distortions are slow and smooth in motion and fleeting in their appearance.

- Colour shifting

- Tracers

- After images

- Depth perception distortions

- Environmental patterning

- Perspective distortions

- Recursion

- Symmetrical texture repetition

- Scenery slicing

Geometry

The visual geometry of LSD can be described as more similar in appearance to that of 2C-B or 2C-I than psilocybin, LSA or DMT.It can be exhaustively described as primarily intricate in complexity, algorithmic in form, unstructured in organization, brightly lit, colourful in scheme, synthetic in feel, multicoloured in scheme, flat in shading, sharp in edges, large in size, fast in speed, smooth in motion, angular in its corners, non-immersive in-depth and consistent in intensity.

At higher doses, it tends to produce states of Level 8A visual geometry over Level 8B. Very high doses saturating serotonin receptors tend to saturate one's visual perception from rainbow geometry to a white void.

Hallucinatory states

LSD is capable of producing a full range of low and high-level hallucinatory states; however, they are significantly less consistent and reproducible than that of other psychedelic tryptamines such as DMT or psilocybin mushrooms. These effects include:

- Transformations

- Machinescapes - A rare effect that typically only occurs at very strong to heavy doses, and not as consistently as with certain psychedelics such as DMT, psilocybin mushrooms, 2C-P, and atypical psychedelics like salvia.

- Internal hallucination (autonomous entities; settings, sceneries, and landscapes; perspective hallucinations and scenarios and plots) - Although some users report that LSD is capable of producing hallucinatory states with the same intensity and vividness as psilocybin mushrooms or DMT, it is much rarer and less consistent. While traditional psychedelics such as LSA, ayahuasca and mescaline will induce internal hallucinations near consistently at level 5 geometry and above, some users claim that LSD tends to go straight into Level 8A visual geometry.

This lack of consistently induced hallucinatory breakthroughs means that for most, LSD is relatively limited in depth, at doses that do not come with excessive side effects.

- External hallucination (autonomous entities; settings, sceneries, and landscapes; perspective hallucinations and scenarios and plots)

Cognitive effects

-

- Analysis enhancement - Some users report gaining the ability to analyze situations in novel and relatively objective ways. It is not clear if this is actually the case, or just a feeling generated by the substance.

- Anxiety & Paranoia - Not typically observed at low to common doses and are less likely to occur when the basic rules of set and setting are taken into account.[note 3]

- Conceptual thinking - A signature effect. LSD may allow the user to bypass normal cognitive patterns (and their associated limitations). Manifests as lateral or abstract thinking patterns.

- Cognitive euphoria - Cognitive euphoria is limited and inconsistent compared to that of MDMA, cocaine, and opioids. Unlike the aforementioned substances, mental euphoria on psychedelics is "unforced", meaning it requires a pre-existing positive emotional state.

- Euthymia - This effect manifests itself acutely for all classical psychedelics when one to three doses are combined with a psychotherapy treatment program. When comparing meta analyses, psychedelic psychotherapy greatly outperforms "gold standard" treatments for several mental health problems.

- Introspection - Present at most doses. May occur alongside personal bias suppression.

- Personal bias suppression - The user may feel they have the ability to analyze their lives or relationships in a more objective way. It is not clear if this is actually the case, or just a feeling generated by the substance.

- Creativity enhancement - LSD is well-known for its ability to enhance creativity and out-of-the-box thinking. A large number of artists, musicians, scientists, and other intellectuals have used it, dating to the 1950s.[48]

- Novelty enhancement - Very prominent on LSD compared to other substances.

- Focus enhancement - Occurs mostly on low or threshold dosages and feels less forced or sharp than it does with stimulants.

- Immersion enhancement - Very prominent on LSD compared to other substances, second only to dissociative immersion enhancement.

- Personal meaning enhancement - The user may feel as if their experience has special meaning, which may or may not last after the trip. Appears to depend on the user's set and setting.

- Emotion enhancement - The user's ability to experience emotion may be strongly enhanced. This is thought to contribute to its therapeutic effect. Consequently, it is advised to not take LSD when in a low or unstable mood and to follow the principles of set and setting.

- Empathy, affection and sociability enhancement - Can be prominent but also unreliable compared to MDMA. More dose-dependent; higher doses are more likely to cause introspection and social withdrawal.

- Delusion - Mild delusions can occur at common doses. Serious, persisting delusions are typically limited to higher doses or individual susceptibility.

- Déjà vu - Unreliable and usually at higher doses. May indicate an overdose and the beginning of delusions and psychosis.

- Increased libido - Generally inconsistent compared to stimulants and cannabis. Mild to moderate when it does occur.

- Increased music appreciation - Extremely prominent for many users. Likely a part of its therapeutic effect. Sublime or mystical experiences on LSD are often linked to music.

- Increased sense of humor - Very common on LSD, particularly during the come up and peak phases. Users report suddenly finding mundane situations and actions inexplicably hilarious.[note 4]

- Laughter fits - Laughter fits are common, particularly during the come up phase. It can manifest as uncontrollable giggles and laughter that can form a feedback loop if around others who are also under the influence.

- Memory suppression - Present at all dose levels past low-common. Stronger than phenethylamines like mescaline or 2C-B but weaker than tryptamines like psilocybin or DMT.

- Ego loss - A signature effect. May be accompanied by euphoria or dysphoria depending on set and setting. Also accompanied by time distortion and potentially thought loops.

- Motivation enhancement - LSD produces stimulant-like motivation enhancement at low and microdoses, although in a much less prominent or reliable manner.

- Multiple thought streams

- Ego replacement - Ego replacement is very rare and occurs in an unpredictable manner. This effect usually coincides with delusions and may indicate the beginnings of psychosis. It is more likely to occur with high doses.

- Personality regression - True personality regression on LSD is very rare. More commonly, it takes the milder form of the user having strong feelings of early childhood, including repressed memories.

- Simultaneous emotions

- Suggestibility enhancement - Suggestibility to external influences may be strongly enhanced. While potentially beneficial for psychotherapy, this property can be abused by nefarious individuals (e.g. cult leaders). Users are advised to be discerning about who they take LSD with.

- Thought acceleration

- Thought connectivity - A signature effect. Thoughts may feel more fluid and interconnected than usual. May occur alongside conceptual thinking and creativity enhancement.

- Thought loops - Typically occurs at higher doses, and at the peak of the experience. Often accompanied by ego loss. This effect may become exacerbated or triggered by cannabis or stimulants.

- Time distortion - A signature effect. The user's perception of time may be strongly altered. Typically takes the form of time dilation, or the experience of time slowing down and passing much slower than it does while sober.

- Wakefulness - Users report that it is difficult or impossible to go to sleep for up to 10 hours (or more) after LSD ingestion.

- Addiction suppression[49] - Some research suggests LSD can be used to treat addiction. Anecdotally, many users report that psychedelics are helpful for this purpose.

Auditory effects

-

- Auditory enhancement - Some users report an enhanced sense of hearing on LSD. However, there is currently no clinical evidence supporting this claim.

- Auditory distortion - Sounds may appear "tinny" or "alien". More likely at higher doses. Certain subjective reports mention flanging, delays/echoing, reverb-like effects, similar to those found in music.

- Auditory hallucination - Typically present at higher doses. Not as common as visual hallucinations, but may occur alongside them.

Multi-sensory effects

-

- Synaesthesia - True synesthesia is rare and non-reproducible, although users often describe the feeling of being able to "hear colors" and "see sounds". Increasing the dosage can increase the likelihood of occurrence, but seems to primarily occur in those who are already predisposed to synesthetic states.

Transpersonal effects

- Transpersonal states are frequently reported at common to high doses of LSD. They appear to be stronger than most phenethylamines (e.g. mescaline, 2C-B) but weaker than tryptamines (e.g. psilocybin, DMT). Strongly dependent on set and setting.

Combination effects

- Alcohol - Alcohol's depressant effects can be used to reduce some of the anxiety and muscle tension produced by LSD. However, alcohol can also cause dehydration, nausea, and physical fatigue, which can negatively impact the user's mindset (set). Users are advised to pace themselves and drink only a portion of their usual amount if drinking on LSD.

- Benzodiazepines - Benzodiazepines are highly effective at reducing the intensity of LSD's cognitive and visual effects via inhibition of brain electrical activity.

- Dissociatives - LSD enhances the cognitive, visual and general hallucinatory effects of dissociatives. Dissociative-induced holes, spaces, and voids and internal hallucinations become more vivid and intense on LSD. These effects correspond with an increased risk of confusion, delusions, and psychosis.

- MDMA - LSD synergistically enhances the physical, cognitive, and visual effects of MDMA. The synergy between these substances is unpredictable and so it is advised to start with markedly lower doses than one would take for either individually. There is some evidence that suggests LSD can increase the neurotoxicity of MDMA.[50][51][52]

- Antidepressants and antipsychotics may block the effect of LSD by acting on the same receptors and outcompeting its ability to bind. Antidepressants mirtazapine and trazodone act on the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors where they block serotonin and other molecules from binding.[53] Atypical antipsychotics also act on these receptors in order to decrease hallucinations and cognitive distortion.

Experience reports

There are currently 47 experience reports describing the effects of this substance in our experience index. You can also submit your own experience report using the same link.

- Experience: 1 tab LSD - First Time Experience

- Experience: 385μg LSD - A Fruit of My Endeavors

- Experience: 660ug LSD - First bad trip

- Experience: LSD (Unknown dosage) - My experiences with LSD and anorexia/bulemia

- Experience:1 blotter- LSD - My first exorcism

- Experience:1 hit LSD (unknown dosage) - Choose Asia

- Experience:1,55mg LSD - The Report

- Experience:1100ug LSD (oral) - Time reversal, spiders, and the hospital

- Experience:120µg LSD - First Bad Acid Trip, Psychosis

- Experience:130ug LSD - Warmth and the Truth

- Experience:2 hits of LSD + weed - Mindfuck

- Experience:2 x 150 LSD tabs

- Experience:2.5g Peganum Harmala + 250µg LSD - Ecstasy of Love and Misanthropy

- Experience:210ug LSD - Poles at the Peak

- Experience:215µg LSD - Supermarket Amnesia

- Experience:225ug - Sheer Awe and Joy

- Experience:225ug LSD + 9g cubensis - Galactic Melt and the Meverse

- Experience:250ug LSD - Bulk Acid

- Experience:3-MeO-PCP, LSD, Clonazolam, and Amphetamine - Excessive Amounts and Excessive Confusion

- Experience:300 ug of LSD - The mysterious community

- Experience:300ug LSD - Profound religious experience

- Experience:300ug LSD - The Pyramid Universe

- Experience:300µg LSD - Togetherness and the Silent Dusk

- Experience:400ug LSD + 40mg 4-AcO-MET (insufflated) - Meeting Yourself

- Experience:400ug LSD + weed + nitrous -- Fundamental insights into the universe

- Experience:400µg LSD + 7.9g cannabis - Pure Energy

- Experience:437.5μg LSD - Everything at once

- Experience:480ug of LSD in a subway train

- Experience:4x 200ug tabs - You do not need to understand

- Experience:5 tabs LSD + cannabis + nitrous - A lover's ego death

- Experience:660ug LSD - Panic, Terror, Mass Hysteria... Freedom

- Experience:800ug LSD - 3D Vision

- Experience:An intense slap: 60 μg LSD and 280 mg DXM

- Experience:First 105μg LSD - Unlocking The Door

- Experience:Into the Multiverse

- Experience:LSD (120ug) - An Overdose of LSD and Trip into Insanity

- Experience:LSD (150µg) + Cannabis - 150µg lsd and a shitload of weed

- Experience:LSD (220 ug) and Cannabis - Tripping at home

- Experience:LSD (230 ug) - An amazing adventure by vikilikepsych

- Experience:LSD (300 ug) - A Real Wake-Up

- Experience:LSD (388 µg) + Cannabis - The Terror of Eternity

- Experience:LSD (400ug, Oral) - An afternoon in "a" garden

- Experience:LSD (~500μg, sublingual) + Noopept - Mind Reset

- Experience:LSD 500ug Oral Ingestion - Rapid Object Apperance Change

- Experience:MDMA (750mg, Oral) - Finally Free

- Experience:Unity and interconnectedness

- Experience:Unknown Dosages: 1 psilocin chocolate, 1 hit LSD; Lawing the Mown

Additional experience reports can be found here:

Forms

LSD is typically distributed in various forms for oral or sublingual administration, with blotter paper being the most common:

- Blotters are typically small squares pulled off sheets of perforated blotting paper that have been dipped into an LSD & alcohol solution. These squares may be swallowed, chewed, or held sublingually. Note: chewing blotters should not result in a bitter metallic taste as this can indicate the presence of a 25x-NBOMe or DOx compound (see here for more information).

- Liquid solutions are often found in vials with a pipette. This form is often dropped directly into the mouth or tongue. It may also be dropped onto individual sugar cubes or candy before consumption.[54]

- Tablets & microdots are very small tablets which can be chewed or swallowed.

- Powder can, in theory, be administered orally, sublingually, or via insufflation or injection. However, LSD is rarely encountered or taken in this way in practice due to its incredible potency. It is almost always diluted into a liquid solution or 'laid' onto blotter paper to allow for more accurate and consistent dosing.

- Gel tabs can be taken orally and are small pieces of gelatin which contain LSD. These are less common now than in the past, but are still occasionally present in some areas of the world.

Research

Alcoholism

Some studies in the 1960s that investigated LSD as a treatment for alcoholism found reduced levels of alcohol misuse in almost 60% of those treated, an effect which lasted six months but disappeared after a year.[49][55][49][56][57]

A 2012 meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials found evidence that a single dose of LSD in conjunction with various alcoholism treatment programs was associated with a decrease in alcohol abuse, lasting for several months.[49]

LSD is also sometimes self-administered in a non-medical environment for overcoming addiction.

LSD was studied in the 1960s by Eric Kast as an analgesic for acute and chronic pain caused by cancer or other major trauma.[58] Even at low (i.e. sub-psychedelic) dosages, it was found to be at least as effective as traditional opiates, while being much longer lasting in pain reduction (lasting as long as a week after peak effects had subsided).

Kast attributed this effect to a decrease in anxiety; that is to say that patients were not experiencing less pain, but rather were less distressed by the pain they experienced. This purported effect is being tested using a similar psychedelic substance, in an ongoing (as of 2006) study of the effects of psilocin on anxiety in terminal cancer patients.[citation needed]

Cluster headaches

LSD has been used as a treatment for cluster headaches, an uncommon but extremely painful disorder.

Although the phenomenon has not been fully investigated, case reports suggest that LSD and psilocin can reduce cluster pain and also interrupt the cluster-headache cycle, preventing future headaches from occurring. Currently existing treatments include various tryptamines among other chemicals, so LSD's efficacy in this regard may not be surprising.

A dose-response study testing the effectiveness of both LSD and psilocin was planned at McLean Hospital, although the current status of this project is unclear. A 2006 study by McLean researchers interviewed 53 cluster headache sufferers who treated themselves with either LSD or psilocin, finding that a majority of users of either drug reported beneficial effects.[59]

Unlike the use of LSD or MDMA in psychotherapy, this research involves non-psychological effects and often sub-psychedelic dosages.[60][59]

End-of-life anxiety

From 2008 to 2011 there was ongoing research in Switzerland into using LSD to alleviate anxiety for terminally ill cancer patients coping with their impending deaths. Preliminary results of the study are promising, and no negative effects have been reported.[61][62]

Neuroplasticity

A 2018 study demonstrated neuroplasticity induced by LSD and other psychedelics through TrkB, mTOR, and 5-HT2A signaling.[63]

Reagent results

Exposing compounds to the reagents gives a colour change which is indicative of the compound under test.

| Marquis | Mecke | Mandelin | Liebermann | Froehde | Robadope | Ehrlich | Hofmann | Simon's |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No reaction | No reaction | No reaction | No reaction | No reaction | No reaction | Pink - Purple - Blueish (slow) | Blue | No reaction |

Toxicity and harm potential

Numerous studies have found that LSD is physiologically well-tolerated and has an extremely low toxicity relative to dose. There is no evidence for long-lasting effects on the brain or other organs and there are no documented deaths attributed to the direct effects of LSD toxicity.[66]

However, it is worth noting that while LSD as a chemical may not be capable of causing direct bodily toxicity or death, its improper use can still present serious hazards.

For example, it has the potential to strongly impair the user's judgment and attention span, which may promote erratic or dangerous behaviors. In extreme cases, the user may experience powerful delusions e.g. that they are currently inside of a dream and therefore physically invincible, or that they are being persecuted by malevolent entities. This may prompt them to jump off of a building or a cliff, or run into oncoming traffic.[2]

Additionally, extreme negative reactions and psychotic episodes (i.e. "bad trips") can cause lasting psychological trauma if not properly managed or treated afterward. Extreme negative reactions are uncommon, but are more likely to happen in non-supervised settings and/or with higher doses (i.e. exceeding the "common" range).

Finally, it should be noted that evidence of LSD's effectiveness as a mental health treatment only applies to the controlled procedures used in clinical settings. LSD alone is not considered the treatment because the current evidence suggests it must be combined with professional psychotherapy to produce lasting therapeutic effects.

Without the appropriate safeguards, attempts at self-medicating with LSD may actually worsen mental health issues.[67]

It is strongly advised to use harm reduction practices if using this substance. These include:

- Taking the substance under the supervision of a tripsitter for one's first time or while experimenting with a higher dose

- Starting off with a dose in the low-common range and monitoring for unusual reactions (e.g. mania, delusions) or sensitivity

- Not exceeding the listed heavy dose. If heavy doses are required, a tolerance break is advised instead. Heavy doses greatly increase the risk of negative effects

- Using a reagent testing kit to verify the substance is genuine LSD and not a dangerous counterfeit

- Keeping a supply of benzodiazepines or antipsychotics (e.g. Seroquel) to abort the trip in the case of overwhelming anxiety or psychosis

Psychosis and mental disorder risk

LSD can exacerbate symptoms (e.g. delusions, mania, psychosis) of various mental disorders. Specifically, it can precipitate the early onset of schizophrenia in vulnerable individuals.[66]

Those with a personal or family history of mental disorders, particularly psychotic disorders like schizophrenia, should not use LSD without consulting a qualified medical professional.

Dependence and abuse potential

Like other serotonergic psychedelics, LSD is considered to be non-addictive with a low abuse potential.[66] Notably, there are no literature reports of successful attempts to train animals to self-administer a serotonergic psychedelic, which is predictive of abuse liability, indicating that it does not have the necessary pharmacology to either initiate or maintain dependence.[66] Additionally, there is no human clinical evidence that LSD can cause addiction.

There is virtually no withdrawal syndrome when chronic use is stopped.[68] In one study, morphine addicts administered LSD regularly for weeks did not recognize when the drug was exchanged for a placebo and experienced no withdrawal symptoms.[69]

Tolerance

LSD exhibits significant tachyphylaxis; i.e., tolerance to its effects forms almost immediately after ingestion; i.e., in as little as three hours.[70] Human studies from the 1950s and 60s, when LSD was still legal in the United States, found that tolerance to LSD's effects "requires 3-4 days of daily administration to reach near-maximum levels and 5 days of abstinence to completely reverse."[71]

Some anecdotal reports suggest that extremely high doses of LSD can produce a tolerance that can last subsequently longer, anywhere from weeks to months, and that high doses of LSD, along with high tolerances, can produce unusual variations in LSD's intensity, duration, and effects.

LSD also exhibits cross-tolerance with all psychedelics, meaning that after the use of LSD, all psychedelics will have a reduced effect.

Overdose

Unlike other highly prohibited psychoactive substances, LSD has no known toxic dose; it is effectively impossible to physically overdose on. However, higher doses increase the risk of adverse psychological reactions such as anxiety, paranoia, panic attacks, delusions, psychosis, and, in rare cases, seizures.

Medical attention is usually not needed except in the case of severe psychotic episodes or the suspected ingestion of so-called "fake acid", substances that mimics LSD's effects but carry the risk of physical toxicity and overdose (e.g. 25x-NBOMe or DOx).

Benzodiazepines (e.g. diazepam (Valium), alprazolam (Xanax)) can help to relieve the acute negative psychological effects of LSD. Antipsychotics such as quetiapine (Seroquel) may also be used, although they have more after-effects and potential interactions. Alcohol can also be used as a last resort, but is generally considered to be less effective than other tripkillers, and is sometimes associated with negative interactions.

Mimics ("Fake acid")

The high chemical potency allows LSD to be infused ("laid") onto blotter paper for street distribution. It is sometimes counterfeited by certain other psychedelics that also happen to be potent enough to be laid onto blotter paper (while also being cheaper). Colloquially known as "fake acid" or "bunk acid", the most common adulterant historically is the DOx series, although in recent years the 25x-NBOMe series has become highly prevalent.

Unlike unadulterated LSD blotters, which are usually only mildly bitter or slightly metallic as a byproduct of the blotter paper's ink, mimics are described as having a "metallic", "numbing", "chemical-like", or "extremely bitter or sour" taste. It is advised to immediately spit out any blotters that have a strong bitter taste that exceeds a reasonable level.

However, it is important to note that taste testing is not sufficient to fully protect against mimics. Instead, one should always attempt to test their LSD using a reagent test kit. Testing kits are considered vital because the common mimics have significantly worse safety profiles than LSD, including the risk of physical overdose and death.[citation needed]

Hallucinogen-perception persisting disorder (HPPD)

In rare cases, LSD may trigger hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) in some individuals.[72] The cause is unclear; however, explanations in terms of LSD physically remaining in the body for months or years after consumption have been discounted by experimental evidence.

Some say HPPD is a manifestation of post-traumatic stress disorder, not related to the direct action of LSD on brain chemistry, and varies according to the susceptibility of the individual to the disorder.[73]

Interactions

Dangerous interactions

Warning: Many psychoactive substances that are reasonably safe to use on their own can suddenly become dangerous and even life-threatening when combined with certain other substances. The following list provides some known dangerous interactions (although it is not guaranteed to include all of them).

Always conduct independent research (e.g. Google, DuckDuckGo, PubMed) to ensure that a combination of two or more substances is safe to consume. Some of the listed interactions have been sourced from TripSit.

- Lithium:[74][75] Lithium is commonly prescribed in the treatment of bipolar disorder; however, there is a large body of anecdotal evidence that suggests taking it with psychedelics can significantly increase the risk of psychosis and seizures.[76][77][78] As a result, this combination should be strictly avoided.

- Tricyclic antidepressants:[74] Tricyclic antidepressants increase physical, hallucinatory and psychological responses to LSD.[79] Anecdotal evidence suggests that TCAs increase the risk of bad trips and psychosis when combined with LSD. Since the symptoms are similar to those induced by lithium and LSD, seizures cannot be excluded. Therefore, this combination should be avoided.

- Tramadol:[80] Tramadol is well documented to lower the seizure threshold in individuals[81] and LSD also has the potential to induce seizures in susceptible individuals.[47]

- Ritonavir:[74] Severe vascular constriction has happened when taking ergolines in combination with ritonavir. Because it is not known if this extends to LSD, utmost caution is advised.

- Deliriants (e.g. diphenhydramine, scopolamine): Deliriants should generally not be combined with other substances, but may have additional risks when taken with psychedelics. May increase the risk of anxiety, delusions, mania, psychosis, and serotonin syndrome.

- Cannabis:[80] Cannabis has a strong, volatile synergy with LSD. While often used to intensify or prolong LSD's effects, the combination increases the risk of adverse psychological effects like anxiety, paranoia, panic attacks, and psychosis. Anecdotal reports often describe cannabis use as the triggering event for a bad trip or psychosis.[note 5] Caution is advised.

- Stimulants (e.g. amphetamine, cocaine, methylphenidate):[80] While able to intensify LSD's euphoric effects, stimulants also elevate anxiety levels and increase the risk of paranoia, thought loops, and psychosis, particularly during the comedown phase. This risk may be higher than with other psychedelics due to LSD's direct effect on dopamine pathways. This combination is generally discouraged.

Other interactions

- SSRIs (e.g. fluoxetine, sertraline): Due do the downregulation of 5-HT2A receptors caused by SSRIs, psychedelics can have a reduced effect. Weaker effects could lead to the user compensating by increasing their dose or re-dosing, potentially having stronger effects than they intended. SSRIs can also reduce the chance of having a bad trip due to its anxiolytic effects.

Notable individuals

Some notable individuals have commented publicly on their experiences with LSD.[82][83] Some of these comments date from the era when it was legally available in the US and Europe for non-medical uses, and others pertain to psychiatric treatment in the 1950s and 1960s. Still others describe experiences with illegal LSD, obtained for philosophic, artistic, therapeutic, spiritual, or recreational purposes.

- Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World, became a user of psychedelics after moving to Hollywood. He was at the forefront of the counterculture's use of psychedelics, which led to his 1954 work The Doors of Perception. Dying from cancer, he asked his wife on 22 November 1963 to inject him with 100 µg of LSD. [84]

- Ernst Jünger, German writer and philosopher, throughout his life had experimented with substances such as ether, cocaine, and hashish; and later in life he used mescaline and LSD. These experiments were recorded comprehensively in Annäherungen (1970, Approaches). The novel Visit to Godenholm|Besuch auf Godenholm (1952, Visit to Godenholm) is clearly influenced by his early experiments with mescaline and LSD. He met with LSD inventor Albert Hofmann and they took LSD together several times.[85] He is the inventor of the term "psychonaut".

- Timothy Leary, an American psychologist and early psychedelic researcher, became one of the most visible public advocates of LSD during the 1960s. While at Harvard University, he co-led the Harvard Psilocybin Project and later worked with LSD before his dismissal in 1963. Leary promoted psychedelics as tools for introspection, behavioural change, and what he described as “neurological self-direction.” He also coined the counterculture phrase “turn on, tune in, drop out,” reflecting his emphasis on intentional mindset and environment. Speaking about the experiential depth of LSD, he stated: “The LSD experience puts you in touch with the wisdom of your body, of your nervous system, of your cells, of your organs. And the closer you get to the message of the body, the more obvious it becomes that it's constructed and designed to procreate and keep the life stream going."[86]

- Jerry Garcia stated in a July 3, 1989 interview, in response to the question "Have your feelings about LSD changed over the years?," "They haven't changed much. My feelings about LSD are mixed. It's something that I both fear and that I love at the same time. I never take any psychedelic, have a psychedelic experience, without having that feeling of, "I don't know what's going to happen." In that sense, it's still fundamentally an enigma and a mystery."[87]

- Kary Mullis is reported to credit LSD with helping him develop DNA amplification technology, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993.[88]

- Oliver Sacks, a neurologist famous for writing best-selling case histories about his patients' disorders and unusual experiences, talks about his own experiences with LSD and other perception altering chemicals, in his book, Hallucinations.[89]

- Paul McCartney said that The Beatles' songs "Day Tripper" and "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" were inspired by LSD trips. Nonetheless, John Lennon consistently stated over the course of many years that the fact that the initials of "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" spelled out L-S-D was a coincidence (the title came from a picture drawn by his son Julian) and that the band members did not notice until after the song had been released, and Paul McCartney corroborated that story.[90] John Lennon, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr also used the substance, although McCartney cautioned that "it's easy to overestimate the influence of drugs on the Beatles' music."[91]

- Richard Feynman, a notable physicist at California Institute of Technology, tried LSD during his professorship at Caltech. Feynman largely sidestepped the issue when dictating his anecdotes; he mentions it in passing in the "O Americano, Outra Vez" section.[92][93]

- Steve Jobs, co-founder and former CEO of Apple Inc., said, "Taking LSD was a profound experience, one of the most important things in my life."[94]

- W. H. Auden, the poet, said, "I myself have taken mescaline once and LSD once. Aside from a slight schizophrenic dissociation of the I from the Not-I, including my body, nothing happened at all."[95] He also said, "LSD was a complete frost. … What it does seem to destroy is the power of communication. I have listened to tapes done by highly articulate people under LSD, for example, and they talk absolute drivel. They may have seen something interesting, but they certainly lose either the power or the wish to communicate."[96] He also said, "Nothing much happened but I did get the distinct impression that some birds were trying to communicate with me."[97]

Legal status

Internationally, the UN 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances requires its parties to prohibit LSD. Hence, it is illegal in all parties to the convention, which includes the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and most of Europe.

Medical and scientific research with LSD in humans is permitted under the 1971 UN Convention, although has been reported to be difficult to actually carry out in practice.[7]

- Australia: LSD is considered a Schedule 9 prohibited substance in Australia under the Poisons Standard.[98] A Schedule 9 substance is a substance which may be abused or misused and the manufacture, possession, sale or use of is prohibited by law except when required for medical or scientific research, or for analytical, teaching or training purposes with approval of Commonwealth and/or State or Territory Health Authorities.[98] Possession of under 5 doses of LSD is decriminalized in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) as of October 28, 2023.[99]

- Austria: LSD is illegal to possess, produce and sell under the Addictive Substances Act (Suchtmittelgesetz).[100][7]

- Brazil: Possession, production and sale is illegal as it is listed on Portaria SVS/MS nº 344.[101]

- Canada: LSD is a Schedule III controlled substance in Canada.[102]

- Croatia: LSD is a controlled substance.[103]

- Czech Republic: In 2010, the possession of 5 tabs of LSD has been decriminalized. Anybody possessing less than this amount may be charged for a misdemeanor or receive a warning from police.[104]

- Denmark: LSD is a Category A controlled substance in Denmark.[105]

- Germany: LSD is controlled under Schedule I of the Narcotics Act (Anlage I BtMG)[106], former Opium Act (Opiumgesetz) as of February 25, 1967.[107] It is illegal to manufacture, possess, import, export, buy, sell, procure or dispense it without a license.[108]

- Italy: LSD is a Schedule I (Tabella I) controlled substance.[109]

- Japan: LSD is classified as a narcotic under the Narcotic and Psychotropic Drugs Control Act (麻薬及び向精神薬取締法).[110]

- Latvia: LSD is a Schedule I controlled substance in Latvia.[111]

- Luxembourg: LSD is a prohibited substance. [112]

- The Netherlands: LSD is classified as a List I (Lijst 1) controlled substance under the Opium Law (Opiumwet).[113]

- Norway: LSD is classified as a narcotic.[114]

- Portugal: LSD is illegal to produce, sell or trade in Portugal. However since 2001, individuals found in possession of small quantities (up to 500 µg) are considered sick individuals instead of criminals. The substance is confiscated and the suspects may be forced to attend a dissuasion session at the nearest CDT (Commission for the Dissuasion of Drug Addiction) or pay a fine, in most cases.[115]

- Russia: LSD is a List I (список I) contolled substance. It is illegal to possess, produce and sell.[116]

- Switzerland: LSD is a controlled substance specifically named under Verzeichnis D.[117]

- Sweden: LSD is a Schedule I (Förteckning I) controlled substance.[118] The Swedish supreme court concluded in 2018 that possession of processed plant material containing a significant amount of DMT is illegal. However, possession of unprocessed such plant material was ruled legal.[citation needed]

- United Kingdom: LSD is a Class A controlled substance in the United Kingdom.[119]

- United States: LSD is a Schedule I controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. This means it is illegal to manufacture, buy, possess, process, or distribute without a license from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).[120]

- Poland: LSD is illegal to own, produce and sell under "Wykaz środków odurzających i substancji psychotropowych" and is grouped in "I-P" [121]

See also

External links

References

- LSD (Wikipedia)

- LSD (Erowid Vault)

- LSD (TiHKAL / Isomer Design)

- LSD (Drugs-Forum)

- LSD (DrugBank Online)

Discussion

Harm reduction resources

- Thinking of using LSD for the first time? Here are some things to think about (Global Drug Survey)

- How to have a safe psychedelic trip (Psyche Magazine)

Literature

Experimental

- Passie, T., Halpern, J. H., Stichtenoth, D. O., Emrich, H. M., & Hintzen, A. (2008). The Pharmacology of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide: A Review. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics, 14(4), 295-314. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x

- Schmid, Y., Enzler, F., Gasser, P., Grouzmann, E., Preller, K. H., Vollenweider, F. X., ... & Liechti, M. E. (2015). Acute effects of lysergic acid diethylamide in healthy subjects. Biological psychiatry, 78(8), 544-553. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.015

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., Kaelen, M., Bolstridge, M., Williams, T. M., Williams, L. T., Underwood, R., ... & Nutt, D. J. (2016). The paradoxical psychological effects of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Psychological medicine, 46(7), 1379-1390. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002901

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., Muthukumaraswamy, S., Roseman, L., Kaelen, M., Droog, W., Murphy, K., ... & Nutt, D. J. (2016). Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(17), 4853-4858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518377113

- Nichols, C. D., & Sanders-Bush, E. (2002). A single dose of lysergic acid diethylamide influences gene expression patterns within the mammalian brain. Neuropsychopharmacology, 26(5), 634-642. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00405-5

- Wacker, D., Wang, S., McCorvy, J. D., Betz, R. M., Venkatakrishnan, A. J., Levit, A., ... & Roth, B. L. (2017). Crystal structure of an LSD-bound human serotonin receptor. Cell, 168(3), 377-389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.033

Clinical

- Fuentes, J. J., Fonseca, F., Elices, M., Farré, M., & Torrens, M. (2020). Therapeutic use of LSD in psychiatry: a systematic review of randomized-controlled clinical trials. Frontiers in psychiatry, 943. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00943

General

- Nichols, D. E. (2004). Hallucinogens. Pharmacology & therapeutics, 101(2), 131-181. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011478

Further reading

Books

- Hoffman, Albert. LSD — My Problem Child. McGraw-Hill, 1980.

- Lee, M. A., & Shlain, B. (1992). Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond. Grove Press.

- Grof, S., Hofmann, A., & Weil, A. (2008). LSD psychotherapy (The healing potential of psychedelic medicine). Ben Lomond, CA: Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies.

Press

- Gross, Terry. The CIA's Secret Quest For Mind Control: Torture, LSD And A 'Poisoner In Chief'. NPR. National Public Radio, 9 September 2019. Web.

- Grinspoon, Peter. Back to the Future: Psychedelic Drugs in Psychiatry. Harvard Health, 22 June 2021. Web.

- Ungerleider, Shoshana. A New Era in Psychedelic Medicine. Time, 13 Oct. 2021. Web.

Footnotes

- ↑ For some, it manifests spontaneously at different, unpredictable points throughout the trip, but for most, it maintains a steady presence that rises with the onset and dissipates after the peak.

- ↑ If Level 8A Geometry is reached, an intense sensation of seeming to "become aware of and feel every single nerve ending across your entire body all at once" has been described.

- ↑ This effect is usually reported as feeling comfortable and peaceful, compared to the kind experienced on salvia.

- ↑ Users are advised to monitor their core temperature and be cautious if taking LSD in hot or overcrowded outdoor environments.

- ↑ It is advised to eat a medium sized meal two to three hours before a trip to ensure one has enough energy to last through the whole trip. During the trip, the user may want to eat snacks like fruits or nuts or smoothies instead of full meals to avoid nausea and gastric discomfort.

References

- ↑ Dolder, P. C., Schmid, Y., Haschke, M., Rentsch, K. M., Liechti, M. E. (January 2016). "Pharmacokinetics and Concentration-Effect Relationship of Oral LSD in Humans". International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 19 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyv072. ISSN 1461-1457.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Nichols, David E. (2016). Barker, Eric L., ed. "Psychedelics". Pharmacological Reviews. 68 (2): 264–355. doi:10.1124/pr.115.011478. eISSN 1521-0081. ISSN 0031-6997.

- ↑ Passie, T.; Halpern, J. H.; Stichtenoth, D. O.; Emrich, H. M.; Hintzen, A. "The Pharmacology of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide: A Review" (PDF). CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 14: 295–314. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x. eISSN 1755-5949. ISSN 1755-5930. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 1, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Schmid, Y.; Enzler, F.; Gasser, P.; Grouzmann, E.; Preller, K. H.; Vollenweider, F. X.; Brenneisen, R.; Müller, F.; Borgwardt, S.; Liechti, M. E. (2015). "Acute Effects of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide in Healthy Subjects". Biological Psychiatry. 78 (8): 544–553. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.015. eISSN 1873-2402. ISSN 0006-3223.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Joint Hearing before the Select Committee On Intelligence and the Subcommitte On Health And Scientific Research of the Committee On Human Resources: Ninety-fifth congress: First Session" (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. August 3, 1977. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ↑ David Nichols (December 22, 2005). "LSD: cultural revolution and medical advances". Chemistry World. Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Convention On Psychotropic Substances, 1971" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ↑ Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E., Miech, R. A. (August 2014). Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2013. Volume 2, College Students & Adults Ages 19-55. Institute for Social Research.

- ↑ Sessa, B. (2012). The psychedelic renaissance: reassassing the role of psychedelic drugs in 21st century psychiatry and society. Muswell Hill Press. ISBN 9781908995001.

- ↑ Krebs, Teri S; Johansen, Pål-Ørjan (8 March 2012). "Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 26 (7): 994–1002. doi:10.1177/0269881112439253. eISSN 1461-7285. ISSN 0269-8811. PMID 22406913.

- ↑ Winkelman, Michael (27 January 2015). "Psychedelics as Medicines for Substance Abuse Rehabilitation: Evaluating Treatments with LSD, Peyote, Ibogaine and Ayahuasca". Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 7 (2): 101–116. doi:10.2174/1874473708666150107120011. ISSN 1874-4737. PMID 25563446.

- ↑ Sewell, R. A.; Halpern, J. H.; Pope, H. G. (26 June 2006). "Response of cluster headache to psilocybin and LSD". Neurology. 66 (12): 1920–1922. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000219761.05466.43. eISSN 1526-632X. ISSN 0028-3878. PMID 16801660.

- ↑ De Gregorio, Danilo; Popic, Jelena; Enns, Justine P.; Inserra, Antonio; Skalecka, Agnieszka; Markopoulos, Athanasios; Posa, Luca; Lopez-Canul, Martha; Qianzi, He; Lafferty, Christopher K.; Britt, Jonathan P.; Comai, Stefano; Aguilar-Valles, Argel; Sonenberg, Nahum; Gobbi, Gabriella (25 January 2021). "Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) promotes social behavior through mTORC1 in the excitatory neurotransmission". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (5). doi:10.1073/pnas.2020705118. eISSN 1091-6490. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7865169

. PMID 33495318.

. PMID 33495318.

- ↑ Schimmel, Nina; Breeksema, Joost J.; Smith-Apeldoorn, Sanne Y.; Veraart, Jolien; van den Brink, Wim; Schoevers, Robert A. (23 November 2021). "Psychedelics for the treatment of depression, anxiety, and existential distress in patients with a terminal illness: a systematic review". Psychopharmacology. 239 (1): 15–33. doi:10.1007/s00213-021-06027-y. eISSN 1432-2072. ISSN 0033-3158. PMID 34812901.

- ↑ Lyvers, Michael; Meester, Molly (2012). "Illicit Use of LSD or Psilocybin, but not MDMA or Nonpsychedelic Drugs, is Associated with Mystical Experiences in a Dose-Dependent Manner". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 44 (5): 410–417. doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.736842. eISSN 2159-9777. ISSN 0279-1072.

- ↑ Grof, Stanislav (1993). Realms of the Human Unconscious: Observations from LSD Research. London: Souvenir Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-285-64882-9. Archived from the original on January 28, 2011. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ↑ Lüscher, Christian; Ungless, Mark A. (2006). "The Mechanistic Classification of Addictive Drugs". PLOS Medicine. 3 (11). doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030437. eISSN 1549-1676. ISSN 1549-1277. PMID 17105338.

- ↑ Strassmann, Rick (1984). "Adverse reactions to psychedelic drugs. A review of the literature". Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 172 (10): 577–595. doi:10.1097/00005053-198410000-00001. ISSN 0022-3018. OCLC 1754691. PMID 6384428.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Nichols, David (May 24, 2003). "Hypothesis on Albert Hofmann's Famous 1943 "Bicycle Day"". at Mindstates IV: Berkeley, CA: Transcription & Editing by Erowid. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Hofmann, Albert (1980). LSD - My Problem Child. Translated by Ott, Jonathan. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07029-325-0. OCLC 6251390.

- ↑ Zentner, Joseph L. (1976). "The Recreational Use of LSD-25 and Drug Prohibition". Journal of Psychedelic Drugs. 8 (4): 299–305. doi:10.1080/02791072.1976.10471853. eISSN 2159-9777. ISSN 0279-1072.

- ↑ Veysey, Laurence R. (1978). The Communal Experience: Anarchist and Mystical Communities in Twentieth-Century America. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press. p. 437. ISBN 0-226-85458-2.

- ↑ "Public Law 90-639" (PDF). Erowid. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ↑ Gasser, Peter (1995). "Psycholytic Therapy with MDMA and LSD in Switzerland". Newsletter of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. MAPS. 5 (3): 3–7. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Shulgin, Alexander; Shulgin, Ann (1997). "#26. LSD-25". TiHKAL: The Continuation. United States: Transform Press. ISBN 0-9630096-9-9. OCLC 38503252.

- ↑ "Chemical Datasheet: D-Lysergic Acid Diethylamide". CAMEO Chemicals. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ↑ Li Z, McNally AJ, Wang H, Salamone SJ. Stability study of LSD under various storage conditions. J Anal Toxicol. 1998 Oct;22(6):520-5. doi: 10.1093/jat/22.6.520. PMID: 9788528.

- ↑ Carhart-Harris, R. L.; Muthukumaraswamy, S.; Roseman, L.; Kaelen, M.; Droog, W.; Murphy, K.; Tagliazucchi, E.; Schenberg, E. E.; Nest, T.; Orban, C.; Leech, R.; Williams, L. T.; Williams, T. M.; Bolstridge, M.; Sessa, B.; McGonigle, J.; Sereno, M. I.; Nichols, D.; Hellyer, P. J.; Hobden, P.; Evans, J.; Singh, K. D.; Wise, R. G.; Curran, H. V.; Feilding, A.; Nutt, D. J. (2016). "Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (17): 4853–4858. doi:10.1073/pnas.1518377113. eISSN 1091-6490. ISSN 0027-8424. OCLC 43473694.

- ↑ Aghajanian, G. K.; Bing, O. H. (1964). "Persistence Of Lysergic Acid Siethylamide In The Plasma Of Human Subjects". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 5 (5): 611–614. doi:10.1002/cpt196455611. ISSN 1532-6535. PMID 14209776.

- ↑ Nelson, D. L. (2004). "5-HT5 receptors". Current Drug Targets-CNS & Neurological Disorders. 3 (1): 53–58. doi:10.2174/1568007043482606. ISSN 1568-007X. PMID 14965244.

- ↑ Moreno, J. L.; Holloway, T.; Albizu, L.; Sealfon, S. C.; González-Maeso, J. (2011). "Metabotropic glutamate mGlu2 receptor is necessary for the pharmacological and behavioral effects induced by hallucinogenic 5-HT2A receptor agonists". Neuroscience Letters. 493 (3): 76–79. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2011.01.046. ISSN 0304-3940. OCLC 1874501. PMID 21276828.

- ↑ Krebs-Thomson, Ph.D., K. (May 1998). "Effects of Hallucinogens on Locomotor and Investigatory Activity and Patterns: Influence of 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C Receptors". Neuropsychopharmacology. 18 (5): 339–351. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00164-4. ISSN 0893-133X.

- ↑ Burris, K. D., Breeding, M., Sanders-Bush, E. (1 September 1991). "(+)Lysergic acid diethylamide, but not its nonhallucinogenic congeners, is a potent serotonin 5HT1C receptor agonist". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 258 (3): 891–896. ISSN 0022-3565.

- ↑ Titeler, M., Lyon, R. A., Glennon, R. A. (February 1988). "Radioligand binding evidence implicates the brain 5-HT2 receptor as a site of action for LSD and phenylisopropylamine hallucinogens". Psychopharmacology. 94 (2). doi:10.1007/BF00176847. ISSN 0033-3158.

- ↑ Backstrom, J. (August 1999). "Agonist-Directed Signaling of Serotonin 5-HT2C Receptors Differences Between Serotonin and Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD)". Neuropsychopharmacology. 21 (2): 77S–81S. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00005-6. ISSN 0893-133X.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Nichols, C. (May 2002). "A Single Dose of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide Influences Gene Expression Patterns within the Mammalian Brain". Neuropsychopharmacology. 26 (5): 634–642. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00405-5. ISSN 0893-133X.

- ↑ Marona-Lewicka, Danuta; Thisted, Ronald A.; Nichols, David E. (2005). "Distinct temporal phases in the behavioral pharmacology of LSD: dopamine D2 receptor-mediated effects in the rat and implications for psychosis". Psychopharmacology. 180 (3): 427–435. doi:10.1007/s00213-005-2183-9. eISSN 1432-2072. ISSN 0033-3158. PMID 15723230.

- ↑ Hanna, Jon; Manning, Tania (2012). "The End of a Chemistry Era...: Dave Nichols Closes Shop". Erowid Extracts. Erowid. 23: 2–7. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ↑ Johansen, PØ; Krebs, TS (March 2015). "Psychedelics not linked to mental health problems or suicidal behavior: a population study". Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 29 (3): 270–9. doi:10.1177/0269881114568039. PMID 25744618.

- ↑ Holland D, Passie T (2011) Flashback-Phaenomene als Nachwirkung von Halluzinogeneinnahme VWB-Verlag, Berlin

- ↑ Abraham HD, Duffy FH (1996) Stable qEEG differences in post-LSD visual disorder by split half analysis: evidence for disinhibition. Psychiatry Res 67:173–187

- ↑ Halpern, JH; Lerner, AG; Passie, T (2018). "A Review of Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD) and an Exploratory Study of Subjects Claiming Symptoms of HPPD". Current topics in behavioral neurosciences. 36: 333–360. doi:10.1007/7854_2016_457. PMID 27822679.

- ↑ Halpern, JH; Lerner, AG; Passie, T (2018). "A Review of Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD) and an Exploratory Study of Subjects Claiming Symptoms of HPPD". Current topics in behavioral neurosciences. 36: 333–360. doi:10.1007/7854_2016_457. PMID 27822679.

- ↑ "Does LSD Stay in Your Spinal Cord Forever?". High Times. 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Passie, T; Halpern, JH; Stichtenoth, DO; Emrich, HM; Hintzen, A (2008). "The pharmacology of lysergic acid diethylamide: a review". CNS neuroscience & therapeutics. 14 (4): 295–314. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x. PMID 19040555.

- ↑ Friedman, Steven A.; Hirsch, Stuart E. (1971). "Extreme Hyperthermia After LSD Ingestion". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 217 (11): 1549–1550. doi:10.1001/jama.1971.03190110067020. eISSN 1538-3598. ISSN 0098-7484. OCLC 1124917.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Fisher, D. D.; Ungerleider, J. T. (1967). "Grand mal seizures following ingestion of LSD". California Medicine. 106 (3): 210–211. ISSN 0008-1264. PMC 1502729

. PMID 4962683.

. PMID 4962683.

- ↑ Wießner I, Falchi M, Maia LO, Daldegan-Bueno D, Palhano-Fontes F, Mason NL, Ramaekers JG, Gross ME, Schooler JW, Feilding A, Ribeiro S, Araujo DB, Tófoli LF. LSD and creativity: Increased novelty and symbolic thinking, decreased utility and convergent thinking. J Psychopharmacol. 2022 Mar;36(3):348-359. doi: 10.1177/02698811211069113. Epub 2022 Feb 1. PMID: 35105186.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 Krebs, T. S.; Johansen, P. Ø. (2012). "Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 26 (7): 994–1002. doi:10.1177/0269881112439253. eISSN 1461-7285. ISSN 0269-8811. OCLC 19962867. PMID 22406913.

- ↑ Armstrong, B. D.; Paik, E.; Chhith, S.; Lelievre, V.; Waschek, J. A.; Howard, S. G. (2004). "Potentiation of (DL)‐3,4‐methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)‐induced toxicity by the serotonin 2A receptior partial agonist d‐lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and the protection of same by the serotonin 2A/2C receptor antagonist MDL 11,939". Neuroscience Research Communications. 35 (2): 83–95. doi:10.1002/nrc.20023. eISSN 1520-6769.

- ↑ Gudelsky, Gary A.; Yamamoto, Bryan; Nash, J. Frank (1994). "Potentiation of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-induced dopamine release and serotonin neurotoxicity by 5-HT2 receptor agonists". European Journal of Pharmacology. 264 (3): 325–330. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(94)90669-6. eISSN 1879-0712. ISSN 0014-2999. OCLC 01568459.

- ↑ Capela, J. P.; Fernandes, E.; Remião, F.; Bastos, M. L.; Meisel, A.; Carvalho, F. (2007). "Ecstasy induces apoptosis via 5-HT2A-receptor stimulation in cortical neurons". NeuroToxicology. 28 (4): 868–875. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2007.04.005. ISSN 0161-813X. PMID 17572501.

- ↑ Anttila, S. A. K.; Leinonen, E. V. J. (2001). "A Review of the Pharmacological and Clinical Profile of Mirtazapine". CNS Drug Reviews. 7 (3): 249–264. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00198.x. eISSN 1755-5949. ISSN 1755-5930. OCLC 221972947. PMC 6494141

. PMID 11607047.

. PMID 11607047.

- ↑ Jim Newton (July 27, 1992). "Long LSD Prison Terms--It's All in the Packaging : Drugs: Law can mean decades in prison for minuscule amounts. DEA official says no change is needed". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ↑ Maclean, J. R.; Macdonald, D. C.; Odgen, F.; Wilby, E. (1967). "LSD-25 and Mescaline as Therapeutic Adjuvants: Experience from a Seven Year Study". In Abramson, H. A. The Use of LSD in Psychotherapy and Alcoholism (PDF). New York: Bobbs-Merrill. pp. 74–80. OCLC 302168.

- ↑ Hoffer, A. (1967). "A Program for the Treatment of Alcoholism: LSD, Malvaria and Nicotinic Acid". In Abramson, H. A. The Use of LSD in Psychotherapy and Alcoholism (PDF). New York: Bobbs-Merrill. pp. 353–402. OCLC 302168.

- ↑ Mangini, Mariavittoria (1998). "Treatment of Alcoholism Using Psychedelic Drugs: A Review of the Program of Research". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 30 (4): 381–418. doi:10.1080/02791072.1998.10399714. eISSN 2159-9777. ISSN 0279-1072.

- ↑ Kast, Eric (1967). "Attenuation of anticipation: A therapeutic use of lysergic acid diethylamide". Psychiatric Quarterly. 41 (4): 646–657. doi:10.1007/BF01575629. eISSN 1573-6709. ISSN 0033-2720. OCLC 01715671.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Sewell, R. A.; Halpern, J. H.; Pope, H. G. (2006). "Response of cluster headache to psilocybin and LSD". Neurology. 66 (12): 1920–1922. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000219761.05466.43. eISSN 1526-632X. ISSN 0028-3878. OCLC 960771045.

- ↑ "LSD and Psilocybin Research: Research into psilocybin and LSD as potential treatments for people with cluster headaches". Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. Archived from the original on January 29, 2007. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ↑ dvp (July 28, 2009). "Psychiater Gasser bricht sein Schweigen" (in German). Basler Zeitung. Archived from the original on September 2, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ↑ David Jay Brown (May 26, 2011). "Landmark Clinical LSD Study Nears Completion". Patch. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ↑ Ly, Calvin; Greb, Alexandra C.; Cameron, Lindsay P.; Wong, Jonathan M.; Barragan, Eden V.; Wilson, Paige C.; Burbach, Kyle F.; Soltanzadeh Zarandi, Sina; Sood, Alexander; Paddy, Michael R.; Duim, Whitney C.; Dennis, Megan Y.; McAllister, A. Kimberley; Ori-McKenney, Kassandra M.; Gray, John A.; Olson, David E. (2018). "Psychedelics Promote Structural and Functional Neural Plasticity". Cell Reports. 23 (11): 3170–3182. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.022. ISSN 2211-1247.

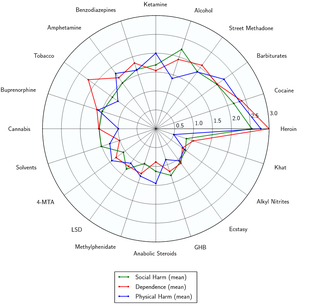

- ↑ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283

. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. Unknown parameter

. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. Unknown parameter |s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ Nutt, D.; King, L. A.; Saulsbury, W.; Blakemore, C. (2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Health Policy. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. eISSN 1872-6054. ISSN 0168-8510. OCLC 10960514. PMID 17382831.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 Nichols, David E. (2004). "Hallucinogens". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 101 (2): 131–181. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.11.002. eISSN 1879-016X. ISSN 0163-7258. OCLC 04981366.

- ↑ "Does LSD have any medical uses?". LSD. Drug Science. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ↑ Balestrieri, A. (1 September 1959). "Acquired and Crossed Tolerance to Mescaline, LSD-25, and BOL-148". Archives of General Psychiatry. 1 (3): 279. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1959.03590030063008. ISSN 0003-990X.

- ↑ Isbell, H. (1 November 1956). "Studies on Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD-25): 1. Effects in Former Morphine Addicts and Development of Tolerance During Chronic Intoxication". A.M.A. Archives of Neurology & Psychiatry. 76 (5): 468. doi:10.1001/archneurpsyc.1956.02330290012002. ISSN 0096-6886.

- ↑ Freedman, D. X. (1984). "LSD: the bridge from human to animal". In Jacobs, B. L. Hallucinogens, neurochemical, behavioral, and clinical perspectives. Central nervous system pharmacology series. Raven Press. ISBN 9780890049907.

- ↑ Buchborn, T., Grecksch, G., Dieterich, D. C., Höllt, V. (2016). "Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse". Tolerance to Lysergic Acid Diethylamide. Elsevier. pp. 846–858. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800212-4.00079-0. ISBN 9780128002124.

- ↑ Halpern, J. H.; Pope Jr, H. G. (2003). "Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder: what do we know after 50 years?" (PDF). Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 69 (2): 109–119. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00306-X. ISSN 0376-8716. PMID 12609692.

- ↑ Lysergic acid diethylamide

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 "LSD: Interactions". Erowid. November 18, 2003. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ↑ Nayak, S., Gukasyan, N., Barrett, F. S., Erowid, E., Erowid, F., Griffiths, R. R. (2021), Classic psychedelic coadministration with lithium, but not lamotrigine, is associated with seizures: an analysis of online psychedelic experience reports, PsyArXiv

- ↑ "wanderlei" (October 3, 2010). "A Nice Little Trip to the Hospital: Lithium & LSD". Erowid Experience Vaults. Erowid. ExpID: 83935. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ↑ "MissDja1a" (December 16, 2008). "Having a Seizure and Passing Out: Lithium & LSD". Erowid Experience Vaults. Erowid. ExpID: 75153. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ↑ "throwaway_naut" (2014). "Please Read: a cautionary tale concerning LSD". r/Psychonaut. Reddit. Retrieved January 7, 2020.