Psilocybin mushrooms

Exercise caution when consuming wild psilocybin mushrooms.

If consuming mushrooms harvested in nature, it is important to understand the risk of mistakenly consuming a poisonous (potentially fatal) look-alike variety.

Please see this section for more information.

| Summary sheet: Psilocybin mushrooms |

| Psilocybin mushrooms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Nomenclature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common names | Psilocybin, Psilocybin mushrooms, Magic Mushrooms, Shrooms, 4-PO-DMT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Substitutive name | 4-Phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systematic name | 3-[2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl]-1H-indol-4-ol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Class Membership | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Psychoactive class | Psychedelic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chemical class | Tryptamine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Routes of Administration | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interactions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cannabis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amphetamines | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cocaine | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tramadol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lithium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Psilocybin mushrooms (also known as magic mushrooms, psychedelic mushrooms, and shrooms) are a family of psychoactive fungi that contain psilocybin, a psychedelic substance of the tryptamine class. The mechanism of action is not fully known, although binding activity at serotonin receptors is thought to be involved.

Psilocybin mushrooms occur on all continents and have been taxonomically classified into over 200 species, the most potent of which belong to the genus Psilocybe.[2] Based on imagery found in prehistoric rock art, they are thought to have been used by various human cultures since before recorded history.

After being introduced to the Western world in the 1950s, they generated substantial public interest.[3] Along with LSD, they were incorporated into the youth counterculture movement of the 1960s. Widespread usage of psychedelics provoked a societal backlash, and they were prohibited in 1970.[citation needed]

Today, they are among the most widely used psychedelic substances (partly due to the ease of personal cultivation and harvesting). As a part of the so-called "psychedelic renaissance",[4] they are currently being investigated in the treatment of a number of ailments including anxiety, depression, addiction, and other mental disorders.[3]

Subjective effects include visual geometry, hallucinatory states, time distortion, enhanced introspection, conceptual thinking, euphoria, and ego loss. The intensity and duration of effects can vary greatly depending on factors such as species and batch, which can complicate standardized dosing information (see this section). They are often described to evoke entheogenic, mystical-like, or transpersonal experiences that may facilitate self-reflection and personal growth.

In distinction to psychedelics like LSD, mescaline, and 2C-B, which may be described as "stimulating", "cerebral", and "bright", psilocybin mushrooms are typically described as having an "earthy", "subliminal", or "dream-like" quality. They also are reported to produce slightly more emotion enhancement, time distortion and ego loss than the aforementioned substances, as well as more nausea, confusion, and sedation.

Unlike most highly prohibited substances, psilocybin mushrooms have low abuse potential and are neither addictive nor physiologically toxic.[5] However, adverse psychological reactions such as severe anxiety, paranoia, delusions and psychosis are always possible, particularly among individuals predisposed to mental disorders.[6]

It is highly advised to use harm reduction practices if using this substance.

History and culture

A growing body of evidence suggests that psychoactive mushrooms have been used by humans in religious ceremonies for thousands of years. In Mesoamerica, they have been consumed in ritual ceremonies for 3000 years.[3]

For example, murals dated 9000 to 7000 BCE found in the Sahara desert in southeast Algeria depict horned beings dressed as dancers holding mushroom-like objects.[7] 6,000-year-old pictographs discovered near the Spanish town of Villar del Humo illustrate several mushrooms that have been tentatively identified as Psilocybe hispanica, a hallucinogenic species native to the area.[8]

Archaeological artifacts from Mexico have also been interpreted by some scholars as evidence for ritual and ceremonial usage of psychoactive mushrooms in the Mayan and Aztec cultures of Mesoamerica.[citation needed] In Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, the mushrooms were called teonanácatl, or "God's flesh".

Following the arrival of Spanish explorers to the New World in the 16th century, chroniclers reported the use of mushrooms by the natives for ceremonial and religious purposes. Accounts describe mushrooms being eaten in festivities for the accession of emperors and the celebration of successful business trips by merchants.[9]

After the defeat of the Aztecs, the Spanish forbade traditional religious practices and rituals that they considered "pagan idolatry", including ceremonial mushroom use. For the next four centuries, the Indians of Mesoamerica hid their use of entheogens from the Spanish authorities.[citation needed]

American banker and amateur ethnomycologist R. Gordon Wasson studied the ritual use of psychoactive mushrooms by the native population of a Mazatec village in Mexico. In 1957, Wasson described the psychedelic visions that he experienced during these rituals in "Seeking the Magic Mushroom", an article published in Life magazine.[10] Later that year, they were accompanied on a follow-up expedition by French mycologist Roger Heim, who identified several of the mushrooms as Psilocybe species.[11]

Heim cultivated the mushrooms in France, and sent samples for analysis to Albert Hofmann, a chemist employed by the Swiss pharmaceutical company Sandoz (now Novartis). Hofmann, who had in 1938 created LSD, led a research group that isolated and identified the psychoactive compounds from Psilocybe mexicana.[12][13]

He and his colleagues later synthesized a number of compounds chemically related to the naturally occurring psilocybin, to see how structural changes would affect psychoactivity. These included 4-HO-DET and 4-AcO-DMT. Sandoz marketed and sold pure psilocybin under the name "Indocybin" to clinicians worldwide without any reports of serious complications.[14][15]

In the early 1960s, Harvard University became a testing ground for psilocybin via the efforts of Timothy Leary and his associates, Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert, under a project known as the Harvard Psilocybin Project. Leary obtained synthesized psilocybin from Hofmann through Sandoz. Some studies, such as the Concord Prison Experiment, found promising results for psilocybin's utility in clinical psychiatry.[16][17]

Leary and Alpert's zealous advocacy for widespread hallucinogen use led to a well-publicized termination from Harvard. In response to concerns about the increase in unauthorized use of psychedelic substances by the general public, psychedelics like psilocybin began to receive negative press and faced increasingly restrictive laws.

In the United States, laws were passed in 1966 that prohibited the production, trade, or ingestion of hallucinogenic substances. Sandoz stopped producing LSD and psilocybin the same year.[18] Further backlash against LSD usage swept psilocybin along with it into the Schedule I category of illicit substances in 1970. Subsequent restrictions on the use of these substances in human research made funding for such projects difficult to obtain, and scientists who worked with psychedelic drugs faced being "professionally marginalized".[19]

In 1976 the book Psilocybin Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide was released, written by Terence McKenna.

In 1978 Paul Stamets released Psilocybe Mushrooms & Their Allies.

In the 1990s, psychedelic research gradually began to regain traction, particularly in Europe. Advances in the neurosciences and the availability of brain imaging techniques have provided a reason for using substances like psilocybin to probe the "neural underpinnings of psychotic symptom formation including ego disorders and hallucinations".[20]

Recent studies in the United States have attracted attention from the popular press and thrust psilocybin into the vogue again.[21]

Common names

Psilocybin mushrooms have a number of common names. These include: psychedelic mushrooms, magic mushrooms, shrooms, magic truffles, and boomers.

The combination with MDMA is known as hippie-flipping.

Research

Neurogenesis

A low dose (0.1 mg/kg) of psilocybin produced a trend toward increased neurogenesis in the mouse hippocampus 2 weeks after its administration, while a high dose (1 mg/kg) significantly decreased neurogenesis. These results suggest that the effects of psilocybin on neurogenesis are dose- and time-related.[22]

Psychoplastogen

Psilocybin is a psychoplastogen,[23] which refers to a compound capable of promoting rapid and sustained neuroplasticity.

Chemistry

Psilocybin, or 4-phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (4-PO-DMT) is a prodrug that is converted into the pharmacologically active compound psilocin in the body by a dephosphorylation reaction mediated by alkaline phosphatase enzymes.[24] Both psilocybin and psilocin are organic tryptamine compounds. They are chemically related to the amino acid tryptophan, and structurally similar to the neurotransmitter serotonin.

Tryptamines share a core structure comprised of a bicyclic indole heterocycle attached at R3 to an amino group via an ethyl side chain. Psilocybin is substituted at R4 of its indole heterocycle with a phosphoryloxy (-PO) functional group. It also contains two methyl groups CH3- bound to the terminal amine RN. This makes psilocybin the 4-phosphoryloxy ring-substituted analog of DMT.[25]

Psilocybin and psilocin occur in their pure forms as white crystalline powders. Both are unstable in light, particularly while in solution, although their stability at low temperatures in the dark under an inert atmosphere is very good.[26]

Pharmacology

Psilocybin acts as a prodrug to psilocin, meaning it is inactive until it is converted into psilocin in the body. Upon entering the body, psilocybin is dephosphorylated to psilocin in the intestinal mucosa by alkaline phosphatase and nonspecific esterase.[3]

Psilocin's psychedelic effects are believed to come from its agonist activity on serotonin 5-HT2A/C and 5-HT1A receptors.[3] While 5-HT2A receptor agonism is considered necessary for hallucinogenic activity, the role of other receptor subtypes is much less understood.[3]

Unlike LSD, psilocin has no significant effect on dopamine receptors and only affects the noradrenergic system at very high dosages.[28]

Psilocybin has also been shown by fMRI imaging to have a dampening effect on certain brain regions, most notably the Default Mode Network.[citation needed]

Subjective effects

The headspace of psilocybin mushrooms is typically described as extremely relaxing, profound, and stoning in style compared to more stimulating psychedelics such as LSD or 2C-B. They are also regarded as being less clear-headed than other commonly used tryptamines such as 4-AcO-DMT, DMT and ayahuasca. This may be due to the presence of other alkaloids like norbaeocystin.

Disclaimer: The effects listed below cite the Subjective Effect Index (SEI), an open research literature based on anecdotal user reports and the personal analyses of PsychonautWiki contributors. As a result, they should be viewed with a healthy degree of skepticism.

It is also worth noting that these effects will not necessarily occur in a predictable or reliable manner, although higher doses are more liable to induce the full spectrum of effects. Likewise, adverse effects become increasingly likely with higher doses and may include addiction, severe injury, or death ☠.

Physical effects

-

- Neurogenesis[22]

- Sedation - Psilocybin mushrooms are reported to be relaxing, stoning and mildly sedating. This sense of sedation is often accompanied by excessive yawning.

- Spontaneous bodily sensations - The "body high" of psilocybin can be described as a pleasurable, soft and all-encompassing tingling sensation or glow that steadily rises with the onset and hits its limit at the peak. Once the peak of the experience or sensation is reached it can feel incredibly euphoric and tranquil or heavy and immobilizing depending on the dose and setting.

- Perception of bodily heaviness- This effect corresponds to the general sense of sedation and relaxation that characterizes psilocybin experiences, this manifests as a bodily heaviness that discourages movement but is typically only prominent during the first half of the experience. This particular physical effect seems to be more commonly experienced and pronounced with certain “woodlover” species of mushrooms such as Psilocybe azurescens.[citation needed]

- Tactile enhancement - This effect is less prominent than with that of LSD or 2C-B but is still present and unique in its character. It is repeatedly described as feeling very primitive in its nature often times with the small hairs on the user's arms or legs feeling slightly itchy or even ticklish against the skin.

- Changes in felt bodily form - This effect is often accompanied by a sense of warmth or unity and usually occurs around the peak of the experience or directly after. Users can feel as if they are physically part of or conjoined with other objects. This is usually reported as feeling comfortable in its sensations and even peaceful.

- Pain relief - This effect can be considered as less intense when compared with LSD. Like most psychedelics, this effect is likely a result of reductions in inflammation as well as from distortions in sensory processing. This effect, while common, is not guaranteed. An increase in pain perception is also possible.

- Nausea - This effect can be greatly lessened or even completely avoided if the individual has an empty stomach prior to ingestion. It is often recommended that one either refrain from eating for approximately 6 to 8 hours beforehand, or eat a light meal 3 to 4 hours before if they are feeling physically fatigued.

- Changes in felt gravity

- Excessive yawning - This effect seems to be uniquely pronounced among psilocybin and related tryptamines. It can occur to a lesser degree on LSD and very rarely on psychedelic phenethylamines like mescaline. It typically occurs in combination with watery eyes.

- Watery eyes

- Frequent urination

- Muscle contractions

- Olfactory hallucination

- Pupil dilation

- Runny nose

- Increased salivation

- Brain zaps[citation needed] - Although this effect is very rare, it can still occur for those susceptible to it. This component is however much less common and intense than it is with serotonin releasing agents such as MDMA.

- Seizure[citation needed] - This is a rare effect but can happen in a small population of those who are predisposed to them, particularly while in physically taxing conditions such as being dehydrated, undernourished, overheated, or fatigued.

Visual effects

-

Enhancements

- Colour enhancement - Relative to other psychedelics, this effect may appear to be more saturated.

- Pattern recognition enhancement

- Visual acuity enhancement - This effect typically occurs prominently at lower doses and becomes increasingly suppressed as one raises the dose.[citation needed]

Distortions

- Drifting (melting, flowing, breathing and morphing) - In comparison to other psychedelics, this effect can be described as highly detailed, realistic, slow and smooth in motion and static in appearance.

- Colour shifting

- Colour tinting

- Visual haze

- Diffraction

- Tracers

- After images

- Symmetrical texture repetition

- Perspective distortions

- Depth perception distortions

- Recursion

- Environmental orbism

- Scenery slicing

Geometry

The visual geometry produced by psilocybin mushrooms can be described as more similar in appearance to that of 4-AcO-DMT, ayahuasca and 2C-E than LSD or 2C-B.It can be comprehensively described through its variations as intricate in complexity, abstract in form, organic in feel, structured in organization, brightly lit, and multicoloured in scheme, glossy in shading, soft in its edges, large in size, slow in speed, smooth in motion, rounded in its corners, non-immersive in-depth and consistent in intensity.

It has a very "organic" feel and at higher dosages is significantly more likely to result in states of Level 8B visual geometry over level 8A.

Hallucinatory states

Psilocybin and its various other forms produce a full range of high-level hallucinatory states in a fashion that is more consistent and reproducible than that of many other commonly used psychedelics. These effects generally include:

- Machinescapes

- Transformations

- Internal hallucination (autonomous entities; settings, sceneries, and landscapes; perspective hallucinations and scenarios and plots) - This effect is very consistent in dark environments at appropriately high dosages. They can be comprehensively described through their variations as lucid in believability, interactive in style, new experiences in content, autonomous in controllability, geometry-based in style and almost exclusively of a personal, religious, spiritual, science-fiction, fantasy, surreal, nonsensical, or transcendental nature in their overall theme.

- External hallucination (autonomous entities; settings, sceneries, and landscapes; perspective hallucinations and scenarios and plots) - These are more common within dark environments and can be comprehensively described through their variations as lucid in believability, interactive in style, new experiences in content, autonomous in controllability, geometry-based in style and almost exclusively of a personal, religious, spiritual, science-fiction, fantasy, surreal, nonsensical or transcendental nature in their overall theme.

Cognitive effects

-

- Emotion enhancement - This effect can be described as being more prominent, consistent and profound when compared to other traditional psychedelics such as mescaline or LSD. This can lead to strong feelings of compassion, urgency and even completely sporadic moments of intense emotional significance that can also be periodically affected by enhancement and suppression cycles.

- Empathy, affection, and sociability enhancement - This effect differs from MDMA and other entactogens in that it isn't as central to the experience, feels less forced and more natural and is experienced at a less consistent rate. The sociability enhancement in particular only occurs rarely and it appears to be more emotional.

- Euthymia - This effect manifests itself acutely for all classical psychedelics when one to three doses are combined with a psychotherapy treatment program. When comparing meta-analyses, psychedelic psychotherapy greatly outperforms "gold standard" treatments for several mental health problems.

- Language suppression - This effect can be described as a perceived inability or general unwillingness to talk aloud despite feeling perfectly capable of formulating coherent thoughts within one's internal narrative. It is much more common among inexperienced users.

- Analysis enhancement - This effect is consistent in its manifestation and outrospection dominant.

- Enhancement and suppression cycles - This can be described as constant waves of extremely stimulated and profound thinking which are spontaneously surpassed in a cyclic fashion by waves of general thought suppression and mental intoxication. These two states seem to switch between each other in a consistent loop once every 20 to 60 minutes.

- Feelings of impending doom - This effect is usually only experienced during the come up phase but typically completely passes or subsides once the primary effects begin. It should be noted that this effect is relatively consistent and normal for psilocybin and related tryptamines which is why a positive and well-informed mindset is key. Less regularly, this aspect can also occur during the peak but will most often be met afterward with sensations of euphoria, catharsis or rejuvenation.

- Cognitive euphoria

- Autonomous voice communication

- Suggestibility enhancement

- Conceptual thinking

- Thought connectivity

- Thought deceleration

- Thought loops

- Thought organization

- Confusion - This effect occurs at a higher rate than other psychedelics such as LSD or DMT. It is more commonly observed in users who are inexperienced with psilocybin, or psychedelics in general

- Novelty enhancement

- Creativity enhancement

- Delusion

- Déjà vu

- Increased music appreciation

- Immersion enhancement

- Memory enhancement

- Memory suppression

- Mindfulness

- Simultaneous emotions

- Personal bias suppression

- Ego replacement - Although this effect is rare and more likely to occur with certain psychedelics like DMT or ayahuasca, it can still spontaneously occur, usually with higher doses.

- Personality regression - Although this effect is rare it can still manifest spontaneously and is thought to depend primarily on the user's set and setting.

- Catharsis

- Rejuvenation - While this component can occur spontaneously at any point, it typically follows a difficult phase of the experience, if not the entire experience itself. It is however almost always felt during the offset of a psilocybin experience and tends to slowly transition into the after effects which are generally described as positive. These positive or mindful after effects are sometimes referred to as an "afterglow" and is both common and consistent for psilocybin and related tryptamines.

- Addiction suppression[29]

- Time distortion

Auditory effects

Multi-sensory effects

-

- Synaesthesia - In its fullest manifestation, this is a very rare and non-reproducible effect. Increasing the dosage can increase the likelihood of this occurring, but seems to only be a prominent part of the experience among those who are already predisposed to synaesthetic states.

- Dosage independent intensity[citation needed]

Transpersonal effects

- Anecdotally, these components are generally considered to be most consistent with the naturally-occurring entheogenic tryptamines such as ayahuasca, ibogaine and psilocybin. They are listed below as follows:

Combination effects

- Cannabis - Cannabis majorly amplifies the sensory and cognitive effects of psilocybin mushrooms. This should be used with extreme caution, especially if one is not experienced with psychedelics. This interaction can also amplify the anxiety, confusion and delusion producing aspects of cannabis significantly. Those who choose to use this combination are advised to start off with only a fraction of their usual cannabis dose, and slow down the pace of their normal intake considerably.

- Dissociatives - Dissociatives can enhance the geometry, euphoria, dissociation and hallucinatory effects of psilocybin mushrooms. Dissociative-induced holes, spaces, and voids while under the influence of psilocybin can result in significantly more vivid visuals than dissociatives alone, along with more intense internal hallucinations, confusion, nausea, delusions and increased risk of psychosis.

- MDMA - MDMA enhances the visual, physical and cognitive effects of psilocybin. The synergy between these substances is unpredictable, and it is advised to start with lower dosages than one would take for either substance individually. The toxicity of this combination is unknown, although there is some evidence that suggests this may increase the neurotoxic effects of MDMA.[30][31][32]

- Alcohol - This combination is not typically recommended due to alcohol’s potential to cause dehydration, nausea, and physical fatigue at higher doses. However, this combination is reasonably safe in low doses and, when used responsibly, can "take the edge off a trip" and reduce anxiety in a manner somewhat similar to benzodiazepines. With psilocybin mushrooms in particular it is often recommended that the user waits until the "come down" phase to consume alcohol due to the sometimes nauseating effects of mushrooms, especially within the first 2 - 3 hours of the experience.

- Benzodiazepines - Depending on the dosage, benzodiazepines can slightly to completely reduce the intensity of the cognitive, physical and visual effects of a psilocybin trip. They can be very efficient at largely stopping or mitigating a bad trip at the cost of amnesia and reduced trip intensity. Caution is advised when acquiring them for this purpose, however, due to the high abuse potential they possess.

- Psychedelics - When used in combination with other psychedelics, the physical, cognitive and visual effects of each substance intensify and synergize strongly with each other. The synergy between those substances is unpredictable, and for this reason, is generally not advised. If choosing to combine psychedelics, it is recommended to start with lower dosages than one would take for either substance individually.

Experience reports

There are currently 30 anecdotal reports which describe the effects of this compound within our experience index.

- Experience: 1.5g Psilocybe Cubensis - Analysis of body and mind

- Experience: 2g Psilocybe cubensis (Lemon Tek) + 0.25mg Cannabis (Bong) - Passing through The Doors to the Eternal Summer

- Experience:1.5 Grams Psilocybe Cubensis

- Experience:10 g psilocybin mushrooms - Paul Stamets’ stuttering transformation

- Experience:15g Psilocybe Mexicana Truffles - First experince

- Experience:15g psilocybe truffles - first experience

- Experience:1g of stars and love

- Experience:2 grams Psilocybe Cubensis + 2.7 grams Syrian Rue - The Psilohuasca Albino Fox

- Experience:2.5g - Swim's first mushroom trip

- Experience:2.5g Mushrooms + 500mg DMT

- Experience:2.5g Psilocybe Cubensis B+ strain - epiphany of nondualistic reality

- Experience:225ug LSD + 9g cubensis - Galactic Melt and the Meverse

- Experience:3 Grams of Mushrooms - Reset on my Life, Experiencing Satori and the Cosmic Perspective

- Experience:3.5g psilocybe cubensis - Relinquishing of Material Chains/Fear and Desolation

- Experience:3g - I found god inside of myself

- Experience:4.5g - The Grand Introduction to Beauty and Fear

- Experience:4g - States of unity and interconnectedness

- Experience:5.3g psilocybe cubensis - Dimensional Circumstance and the Fabric of Understanding

- Experience:5g Mushrooms - Failed attempt at a Terence Mckenna style trip.

- Experience:A Strong Trip: Disconnecting from Reality and Forgetting the World

- Experience:Cubensis genius trials

- Experience:Mushrooms (~0.5 g) - Autonomous Voice

- Experience:Mushrooms and Snuff Films -- Trip Report (3.5 grams)

- Experience:Psilocybe Cubensis (2g, Oral) - First Spiritual Experience(?)

- Experience:Psilocybin Mushroom (0.16 g, Oral) - Dosage Independent Intensity

- Experience:Psilocybin mushrooms (~4.8 g) - A challenging first trip

- Experience:Psilocybin or O-Acetylpsilocin (8000mg oral) - Don't you see? Don't you realize?

- Experience:Psilocybin truffles (15g, tea) - Untitled

- Experience:Unknown dosage - An omniscient sphere

- Experience:~80-100 Psilocybe Subaeruginosa

Additional experience reports can be found here:

Dosage and preparation

The dosage of psilocybin mushrooms depends on the potency of the mushroom (the total psilocybin and psilocin content of the mushrooms), which varies significantly both between species and within the same species. However, "the most commonly used mushroom is Psilocybe cubensis, which contains 10–12 mg of psilocybin per gram of dried mushrooms".[33]

The concentration of active psilocybin mushroom compounds varies not only from species to species, but also from mushroom to mushroom inside a given species, subspecies or variety. The same holds true even for different parts of the same mushroom.

For example, in the species Psilocybe samuiensis, the dried cap of the mushroom contains the most psilocybin at about 0.23%–0.90%. The mycelium contains about 0.24%–0.32%.[34]

Psilocybin

Dosage calculation

Math: Desired psilocybin from divided by the psilocybin strength of the strain. For example, if you want to consume 15 mg psilocybin (a common dose) from cubensis with 1% psilocybin content:

- 15 mg / 1% = 15/0.01 = 1500 mg = 1.5 g

Psilocybe cubensis

Psilocybe cubensis (also known as cubes) is one of the most commonly used species of psilocybin mushrooms. The doses for oral consumption for dried cubensis mushrooms are generally considered to be:

- Threshold: 0.25 - 0.5 g

- Light: 0.5 - 1 g

- Common: 1 - 2.5 g

- Strong: 2.5 - 5 g

- Heavy: 5 g +

Preparation methods

Preparation methods for this compound within our tutorial index include:

- Brown rice flour psilocybin mushroom tek

- Outdoor mushroom cultivation

- Mushroom chocolates

- Mushroom tea

- Psilocybin mushroom lemon tek

Natural occurrence

Biological genera containing psilocybin mushrooms include Copelandia, Galerina, Gymnopilus, Inocybe, Mycena, Panaeolus, Pholiotina, Pluteus, and Psilocybe. Over 100 species are classified in the genus Psilocybe.

Some common psilocybin and psilocin containing mushroom species include:

Psilocybe

|

Panaeolus

Gymnopilus

Dictyonema

|

Risk of species confusion

As psilocybin mushrooms are capable of being harvested in nature, there is a major risk in misidentifying the mushroom species and accidentally consuming a poisonous (possibly lethal) variety. This risk can be avoided by educating oneself in advance on how to properly identify the correct species of mushroom and the potential look-alike mushrooms found within one's local area. Users are encouraged to learn from a mentor who is experienced in mushroom picking before doing it on their own.

Research

Antidepressant effects

While further research is needed to establish the utility of psilocybin and other psychedelics in treating depression, a pilot study has observed significantly decreased depression scores in terminal cancer patients six months after treatment with psilocybin.[35]

An open-label study was carried out in 2016 in the UK to investigate the feasibility, safety and efficacy of psilocybin in treating patients with unipolar treatment-resistant depression with promising results; although the study was small and involved only twelve patients, seven of those patients met formal criteria for remission one week following psilocybin treatment and five of those were still in remission from their depression at three months.[36]

The mechanism behind this is not known as of yet, but researchers have suggested that psilocin's deactivation of the medial prefrontal cortex[37] (mPFC) may be relevant to its antidepressant effects, as the mPFC is known to be elevated in depression and normalized after effective treatment.[37] mPFC hyperactivity has been associated with trait rumination.[38]

Another possible factor to psilocybin's potential against depression may be that depressed patients with high levels of dysfunctional attitudes were found to have low levels of 5-HT(2A) agonism.[39][40]

Toxicity and harm potential

Numerous studies have found that psilocybin mushrooms are physiologically well-tolerated and has an extremely low toxicity relative to dose. There is no evidence for long-lasting effects on the brain or other organs and there are no documented deaths attributed to the direct effects of psilocybin mushrooms toxicity.[43]

However, it is worth noting that while they may not be capable of causing direct bodily toxicity or death, their use can still present serious hazards.

For example, they are capable of strongly impairing the user's judgment and attention span, which may promote erratic or dangerous behaviors. In extreme cases, the user may experience powerful delusions e.g. that they are actually inside of a dream and therefore physically invincible, or that they are being "chased by demons". This may prompt them to jump off of a building or run into oncoming traffic.[43]

Additionally, intense negative experiences and psychotic episodes (i.e. "bad trips") can cause lasting psychological trauma if not properly managed or treated afterward. This is particularly a concern in non-supervised settings or when heavy doses are used.

Finally, it should be noted that evidence of psilocybin mushrooms' effectiveness as a mental health treatment only applies to the controlled procedures used in clinical settings. They are not considered the entire treatment because the current evidence suggests they must be combined with professional psychotherapy to produce lasting effects.

Without the appropriate safeguards, attempts at self-medicating with psilocybin mushrooms may actually worsen mental health issues.[citation needed]

It is strongly advised to use harm reduction practices if using this substance. These include:

- Taking the substance under the supervision of a tripsitter for one's first time or while experimenting with a higher dose

- Starting off with a dose in the low-common range and monitoring for unusual reactions (e.g. mania, delusions) or sensitivity

- Not exceeding the listed heavy dose. If heavy doses are required, a tolerance break is advised instead. Heavy doses greatly increase the risk of negative effects

- Keeping a supply of benzodiazepines or antipsychotics (e.g. Seroquel) to abort the trip in the case of overwhelming anxiety or psychosis

Lethal dosage

The toxicity of psilocybin and psilocin is extremely low. In rats, the median lethal dose (LD50) of psilocybin when administered orally is 280 milligrams per kilogram (mg/kg).

Psilocybin comprises approximately 1% of the weight of Psilocybe cubensis and so nearly 1.7 kilograms (3.7 lb) of dried mushrooms or 17 kilograms (37 lb) of fresh mushrooms would be required for a 60 kilogram (130 lb) person to reach the 280 mg/kg LD50 value of rats.

Based on the results of animal studies, the lethal dose of psilocybin has been extrapolated to be 6 grams, 1000 times greater than the effective dose of 6 milligrams. Unlike many highly prohibited substances, it is effectively impossible to physically overdose on.

Psychosis and mental disorder risk

Psilocybin mushrooms can exacerbate symptoms (e.g. delusions, mania, psychosis) of various mental disorders. Additionally, they can precipitate the early onset of schizophrenia in vulnerable individuals.[43]

Those with a personal or family history of mental disorders, particularly psychotic disorders like schizophrenia, should not use psilocybin mushrooms without consulting a qualified medical professional.

Dependence and abuse potential

Like other serotonergic psychedelics, psilocybin mushrooms have low abuse and no physical dependence potential.[44]

There are no literature reports of successful attempts to train animals to self-administer a serotonergic psychedelic, which is predictive of abuse liability, indicating that it does not have the necessary pharmacology to either initiate or maintain dependence.[44]

Additionally, there is no human clinical evidence that psilocybin mushrooms causes addiction. Finally, there is virtually no withdrawal syndrome when chronic use of psilocybin mushrooms is stopped.

Tolerance to the effects of psilocybin builds almost immediately after ingestion. After that, it takes about 3 days for the tolerance to be reduced to half and 7 days to be back at baseline (in the absence of further consumption).

Psilocybin exhibits cross-tolerance with all psychedelics, meaning that after the consumption of psilocybin all psychedelics will have a reduced effect.

Hallucinogen-perception persisting disorder (HPPD)

In rare cases, psilocybin mushrooms may trigger hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) in some individuals.[45] The cause is unclear; however, explanations in terms of psilocybin physically remaining in the body for months or years after consumption have been discounted by experimental evidence.

Some say HPPD is a manifestation of post-traumatic stress disorder, not related to the direct action on brain chemistry, and varies according to the susceptibility of the individual to the disorder.[46]

Dangerous interactions

Warning: Many psychoactive substances that are reasonably safe to use on their own can suddenly become dangerous and even life-threatening when combined with certain other substances. The following list provides some known dangerous interactions (although it is not guaranteed to include all of them).

Always conduct independent research (e.g. Google, DuckDuckGo, PubMed) to ensure that a combination of two or more substances is safe to consume. Some of the listed interactions have been sourced from TripSit.

- Amphetamines - Stimulants increase anxiety levels and the risk of thought loops which can lead to negative experiences

- Cannabis:[47] Cannabis can have an unexpectedly strong and unpredictable synergy with psilocybin mushrooms. While it is commonly used to intensify or prolong the mushrooms' effects, caution is highly advised as mixing these substances can significantly increase the risk of anxiety, paranoia, panic attacks, and psychosis. Anecdotal reports often describe the ingestion of cannabis as the triggering event for a bad trip or psychosis. Users are advised to start off with only a fraction (e.g. 1/4th - 1/3rd) of their typical cannabis dose and space out hits to avoid accidental over-intake.

- Cocaine - Stimulants increase anxiety levels and the risk of thought loops which can lead to negative experiences

- Tramadol - Tramadol is well known to lower seizure threshold and psychedelics also cause occasional seizures.

- Lithium - Lithium is commonly prescribed in the treatment of bipolar disorder; however, studies find it can significantly increase the risk of and seizures when combined to psychedelics. As a result, this combination should be strictly avoided.

Legal status

Internationally, psilocybin (but not psilocybin mushrooms) is a Schedule I drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

"The cultivation of plants from which psychotropic substances are obtained is not controlled by the Vienna Convention. . . . Neither the crown (fruit, mescal button) of the Peyote cactus nor the roots of the plant Mimosa hostilis nor Psilocybe mushrooms themselves are included in Schedule 1, but only their respective principals, mescaline, DMT, and psilocin."

- Austria: Psilocybin containing mushrooms are illegal to possess in dried form, to sell and to offer, give or get somebody under the SMG (Suchtmittelgesetz Österreich). It is illegal to grow them with the intention of "producing psychotropic substances" (as psilocin and psilocybin) mentioned in BGBl. III Nr. 148/1997 .[48]

- Bahamas: Psilocybin mushrooms are legal to possess, grow, and consume.[citation needed]

- Belgium: Possession and sale of mushrooms have been illegal since 1988.[citation needed]

- Brazil: Psilocybin Mushrooms derived psychoactive substances targeted for unjustified consumption are illegal to possess, store, transport, import, export, prescribe, administer, sell and advertise, regardless of no intent of profit and in any form. Cultivation of the former, however, only under the premise of "botanical purposes", or similar, is perfectly allowed due to legal gap in which Psilocybe mushrooms themselves are not explicitly listed as sources of potential psychotropic substances. Use of Psilocybin containing mushrooms within religious cults are constitucionally and internationally protected from antidrug policies and are, likewise, allowed.[49]

- British Virgin Isles: The sale of mushrooms is illegal, but possession and consumption is legal.[citation needed]

- Bulgaria: The sale of mushrooms is illegal, but possession and consumption is legal.[citation needed]

- Canada: Psilocybin and psilocin are illegal to possess, obtain or produce without a prescription or license as they are Schedule III under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act; however, dried psilocybin mushrooms are openly sold on dozens of Canadian websites. Spores and growing kits are legal to possess. [50]

- Cyprus: Psilocybin mushrooms are illegal to possess, grow, sale, and consume.[citation needed]

- Czech Republic: The distribution (including sale) of mushrooms is illegal, but consumption is legal. The possession of over 40 hallucinogenic caps is considered a crime if they contain more than 50mg of psilocin or the corresponding amount of psilocybin. The possession of more than 40g of hallucinogenic mycelium is considered a crime. If these limits are not exceeded, the act is considered a minor offense and a fine of up to 15 thousand CZK may be imposed.

- Denmark: Psilocybin mushrooms are illegal to possess, grow, sale, and consume.[citation needed]

- Finland: Psilocybin mushrooms are illegal to possess, grow, sale, and consume.[citation needed]

- Germany: Psilocybin is illegal to produce, possess or sale under Schedule I of the Narcotics Act (Anlage I BtMG)[51]. Consumption is not illegal. The mushroom and spores by itself are not illegal and only become illegal when containing Psilocybin or Psilocin.

- Greece: Psilocybin mushrooms are illegal to possess, grow, sale, and consume.[citation needed]

- Iceland: The sale of Psilocybin mushrooms is illegal, but possession and consumption is legal.

- India: Psilocybin mushrooms are illegal to possess, grow, sale, and consume. However, it is reported that many police departments in undeveloped areas are unaware of the prohibition.

- Ireland: Psilocybin mushrooms are illegal to possess, grow, sale, and consume.[citation needed]

- Italy: Psilocybin is a schedule I drug (Tabella 1). [52]

- Japan: Psilocybin mushrooms are illegal to possess, grow, sale, and consume.[citation needed]

- Latvia: Hallucinogenic mushrooms, psilocin and psilocybin are Schedule I controlled substances.[53]

- Luxembourg: Psilocybin is a prohibited substance[54]

- Mexico: The possession, growth, sale and consumption of mushrooms is illegal. Rules are relaxed regarding religious use however.[citation needed]

- The Netherlands: The possession, growth, sale and consumption of mushrooms is illegal. However, due to a legal loophole, psilocybin truffles can be legally possessed, grown, sold and consumed.[citation needed]

- New Zealand: Psilocybin is a Class A substance.[citation needed]

- Norway: Possession, growth, sale and consumption of mushrooms is illegal. Spores, even though not containing psilocybin, are also illegal.[citation needed]

- Sweden: Sveriges riksdag added psilocybin mushrooms to schedule I ("substances, plant materials and fungi which normally do not have medical use") as narcotics in Sweden as of Aug 1, 1999, published by Medical Products Agency.[55]

- Switzerland: Mushrooms of the species Conocybe, Panaeolus, Psilocybe and Stropharia are controlled under Verzechnis D.[56]

- Turkey: The possession, growth, sale and consumption of mushrooms is illegal.[citation needed]

- United Kingdom: According to the 2005 Drugs Act, fresh and prepared psilocybin mushrooms are Class A.[57]

- United States: Psilocybin and psilocin are Schedule I drugs under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. This means it is illegal to manufacture, buy, possess, process, or distribute without a license from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).[58]. Several US states and cities have decriminalised Psilocybin mushrooms.

- Oregon: Oregon Measure 109 legalized the use of Psilocybin mushrooms to licensed service providers administering to individuals 21 years of age or older.

- Colorado: Colorado proposition 122 legalizes psychedelic plants and fungi for adults age 21 and older.

See also

External links

- Psilocybin mushrooms (Wikipedia)

- Magic truffle (Wikipedia)

- Legal status of psilocybin mushrooms (Wikipedia)

- Psilocybin (Wikipedia)

- Psilocybin therapy (Wikipedia)

- Psilocybin mushrooms (Erowid Vault)

- World Wide Distribution of Magic Mushrooms

- Enteogenic Mushrooms - philosophy of cultivation

Discussion

- The Big & Dandy Psilocybin Mushrooms Thread (Bluelight)

- Psilocybin mushrooms, broken down and described (Disregard Everything I Say)

Literature

- McKenna, Terence; McKenna, Dennis (1976). Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide. Under the pseudonyms OT Oss and ON Oeric. Berkeley, CA: And/Or Press. ISBN 978-0-915904-13-6.

- Psilocybe Mushrooms & Their Allies (1978), Homestead Book Company, Template:ISBN

- Passie, T., Seifert, J., Schneider, U., & Emrich, H. M. (2002). The pharmacology of psilocybin. Addiction Biology, 7(4), 357-364. doi: 10.1080/1355621021000005937

- Tylš, F., Páleníček, T., & Horáček, J. (2014). Psilocybin–summary of knowledge and new perspectives. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 24(3), 342-356. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.12.006

- Vollenweider, F. X., & Kometer, M. (2010). The neurobiology of psychedelic drugs: implications for the treatment of mood disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(9), 642-651. doi: 10.1038/nrn2884

- Agurell, S., & Nilsson, J. G. L. (1968). Biosynthesis of Psilocybin Part II*, Incorporation of Labelled Tryptamine Derivatives. Acta Chemica Scandainavica, 22(4). 1210-1218. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a7b9/965618d632ff7de3a96fed11c9455b615d94.pdf

References

- ↑ Pablo Mallaroni, Natasha L. Mason , Johannes T. Reckweg, Riccardo Paci, Sabrina Ritscher, Stefan W. Toennes, Eef L. Theunissen, Kim P.C. Kuypers, Johannes G. Ramaekers (May 2023). "Assessment of the acute effects of 2C-B vs psilocybin on subjective experience, mood and cognition". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. doi:10.1002/cpt.2958.

- ↑ Guzmán, G., Allen, J. W., Gartz, J. (1998). "A worldwide geographical distribution of the neurotropic fungi, an analysis and discussion". Ann. Mus. Civ. Rovereto. 14: 189–280.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Tylš, F., Páleníček, T., Horáček, J. (March 2014). "Psilocybin – Summary of knowledge and new perspectives". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 24 (3): 342–356. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.12.006. ISSN 0924-977X.

- ↑ Sessa, B. (2012). The psychedelic renaissance: reassassing the role of psychedelic drugs in 21st century psychiatry and society. Muswell Hill Press. ISBN 9781908995001.

- ↑ Lüscher, C., Ungless, M. A. (14 November 2006). "The Mechanistic Classification of Addictive Drugs". PLoS Medicine. 3 (11): e437. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030437. ISSN 1549-1676.

- ↑ Strassman, R. J. (October 1984). "ADVERSE REACTIONS TO PSYCHEDELIC DRUGS. A REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE:". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 172 (10): 577–595. doi:10.1097/00005053-198410000-00001. ISSN 0022-3018.

- ↑ Samorini, G. (1992). "The oldest representations of hallucinogenic mushrooms in the world (Sahara Desert, 9000-7000 BP)". Integration. 2 (3): 69–78.

- ↑ Akers, B. P., Ruiz, J. F., Piper, A., Ruck, C. A. P. (June 2011). "A Prehistoric Mural in Spain Depicting Neurotropic Psilocybe Mushrooms?". Economic Botany. 65 (2): 121–128. doi:10.1007/s12231-011-9152-5. ISSN 0013-0001.

- ↑ Hofmann, A. (1980). "The Mexican relatives of LSD". LSD, my problem child. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780070293250.

- ↑ Wasson, R. G. (1957). "Seeking the Magic Mushroom". Life. 42 (19): 100–120. ISSN 0024-3019.

- ↑ Heim, R. (1957). "Notes préliminaires sur les agarics hallucinogènes du Mexique (Preliminary notes on the hallucination-producing agarics of Mexico)". Revue de Mycologie (in French). 22 (1): 58–79.

- ↑ Hofmann, A., Heim, R., Brack, A., Kobel, H. (March 1958). "Psilocybin, ein psychotroper Wirkstoff aus dem mexikanischen Rauschpilz Psilocybe mexicana Heim (Psilocybin, a psychotropic drug from the Mexican magic mushroom Psilocybe mexicana Heim)". Experientia (in German). 14 (3): 107–109. doi:10.1007/BF02159243. ISSN 0014-4754.

- ↑ Hofmann, A., Heim, R., Brack, A., Kobel, H., Frey, A., Ott, H., Petrzilka, Th., Troxler, F. (1959). "Psilocybin und Psilocin, zwei psychotrope Wirkstoffe aus mexikanischen Rauschpilzen (Psilocybin and psilocin, two psychotropic substances in Mexican magic mushrooms)". Helvetica Chimica Acta (in German). 42 (5): 1557–1572. doi:10.1002/hlca.19590420518. ISSN 0018-019X.

- ↑ Marley, G. (9 September 2010). "Psilocybin: gateway to the soul or just a good high?". Chanterelle Dreams, Amanita Nightmares: The Love, Lore, and Mystique of Mushrooms. Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 166. ISBN 9781603582803.

- ↑ Passie, T., Seifert, J., Schneider, U., Emrich, H. M. (October 2002). "The pharmacology of psilocybin". Addiction Biology. 7 (4): 357–364. doi:10.1080/1355621021000005937. ISSN 1355-6215.

- ↑ Leary, T., Litwin, G. H., Metzner, R. (December 1963). "REACTIONS TO PSILOCYBJN ADMINISTERED IN A SUPPORTIVE ENVIRONMENT:". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 137 (6): 561–573. doi:10.1097/00005053-196312000-00007. ISSN 0022-3018.

- ↑ Timothy, L., Ralph, M., Madison, P., Gunther, W., Ralph, S., Sara, K. (1965). "A new behavior change program using psilocybin". Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice. 2 (2): 61–72. doi:10.1037/h0088612. ISSN 0033-3204..

- ↑ Matsushima, Y., Eguchi, F., Kikukawa, T., Matsuda, T. (2009). "Historical overview of psychoactive mushrooms". Inflammation and Regeneration. 29 (1): 47–58. doi:10.2492/inflammregen.29.47. ISSN 1880-9693.

- ↑ Griffiths, R. R., Grob, C. S. (December 2010). "Hallucinogens as Medicine". Scientific American. 303 (6): 76–79. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1210-76. ISSN 0036-8733.

- ↑ Studerus, E., Kometer, M., Hasler, F., Vollenweider, F. X. (November 2011). "Acute, subacute and long-term subjective effects of psilocybin in healthy humans: a pooled analysis of experimental studies". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 25 (11): 1434–1452. doi:10.1177/0269881110382466. ISSN 0269-8811.

- ↑ Keim, B. (1 July 2008). "Psilocybin study hints at rebirth of hallucinogen research". Wired. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Dos Santos, RG; Osório, FL; Crippa, JA; Riba, J; Zuardi, AW; Hallak, JE (June 2016). "Antidepressive, anxiolytic, and antiaddictive effects of ayahuasca, psilocybin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD): a systematic review of clinical trials published in the last 25 years". Therapeutic advances in psychopharmacology. 6 (3): 193–213. doi:10.1177/2045125316638008. PMC 4910400

. PMID 27354908.

. PMID 27354908.

- ↑ Vargas, MV; Meyer, R; Avanes, AA; Rus, M; Olson, DE (2021). "Psychedelics and Other Psychoplastogens for Treating Mental Illness". Frontiers in psychiatry. 12: 727117. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.727117. PMC 8520991

Check

Check |pmc=value (help). PMID 34671279. - ↑ Gilbert, J., Senyuva, H. (2009). Bioactive Compounds in Foods. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444302295.

- ↑ Horita, A., Weber, L. J. (1 January 1961). "Dephosphorylation of Psilocybin to Psilocin by Alkaline Phosphatase". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 106 (1): 32–34. doi:10.3181/00379727-106-26228. ISSN 1535-3702.

- ↑ Anastos, N., Barnett, N. W., Pfeffer, F. M., Lewis, S. W. (April 2006). "Investigation into the temporal stability of aqueous standard solutions of psilocin and psilocybin using high performance liquid chromatography". Science & Justice. 46 (2): 91–96. doi:10.1016/S1355-0306(06)71579-9. ISSN 1355-0306.

- ↑ Petri, G., Expert, P., Turkheimer, F., Carhart-Harris, R., Nutt, D., Hellyer, P. J., Vaccarino, F. (6 December 2014). "Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks". Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 11 (101): 20140873. doi:10.1098/rsif.2014.0873. ISSN 1742-5689.

- ↑ Jerome, L. (2007), Psilocybin Investigator’s Brochure (PDF), Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS).

- ↑ Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., Cosimano, M. P., Griffiths, R. R. (November 2014). "Pilot study of the 5-HT 2A R agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 28 (11): 983–992. doi:10.1177/0269881114548296. ISSN 0269-8811.

- ↑ Armstrong, B. D., Paik, E., Chhith, S., Lelievre, V., Waschek, J. A., Howard, S. G. (September 2004). "Potentiation of (DL)-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-induced toxicity by the serotonin 2A receptior partial agonist d-lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and the protection of same by the serotonin 2A/2C receptor antagonist MDL 11,939". Neuroscience Research Communications. 35 (2): 83–95. doi:10.1002/nrc.20023. ISSN 0893-6609.

- ↑ Gudelsky, G. A., Yamamoto, B. K., Frank Nash, J. (November 1994). "Potentiation of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-induced dopamine release and serotonin neurotoxicity by 5-HT2 receptor agonists". European Journal of Pharmacology. 264 (3): 325–330. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(94)90669-6. ISSN 0014-2999.

- ↑ Capela, J. P., Fernandes, E., Remião, F., Bastos, M. L., Meisel, A., Carvalho, F. (July 2007). "Ecstasy induces apoptosis via 5-HT(2A)-receptor stimulation in cortical neurons". Neurotoxicology. 28 (4): 868–875. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2007.04.005. ISSN 0161-813X.

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/psilocybin

- ↑ Gartz, J., Allen, J. W., Merlin, M. D. (July 1994). "Ethnomycology, biochemistry, and cultivation of Psilocybe samuiensis Guzmán, Bandala and Allen, a new psychoactive fungus from Koh Samui, Thailand". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 43 (2): 73–80. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(94)90006-X. ISSN 0378-8741.

- ↑ Grob, C. S., Danforth, A. L., Chopra, G. S., Hagerty, M., McKay, C. R., Halberstadt, A. L., Greer, G. R. (3 January 2011). "Pilot Study of Psilocybin Treatment for Anxiety in Patients With Advanced-Stage Cancer". Archives of General Psychiatry. 68 (1): 71. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.116. ISSN 0003-990X.

- ↑ Carhart-Harris, R. L., Bolstridge, M., Rucker, J., Day, C. M. J., Erritzoe, D., Kaelen, M., Bloomfield, M., Rickard, J. A., Forbes, B., Feilding, A., Taylor, D., Pilling, S., Curran, V. H., Nutt, D. J. (July 2016). "Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study". The Lancet Psychiatry. 3 (7): 619–627. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30065-7. ISSN 2215-0366.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Carhart-Harris, R. L., Erritzoe, D., Williams, T., Stone, J. M., Reed, L. J., Colasanti, A., Tyacke, R. J., Leech, R., Malizia, A. L., Murphy, K., Hobden, P., Evans, J., Feilding, A., Wise, R. G., Nutt, D. J. (7 February 2012). "Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (6): 2138–2143. doi:10.1073/pnas.1119598109. ISSN 0027-8424.

- ↑ Farb, N. A. S., Anderson, A. K., Bloch, R. T., Segal, Z. V. (August 2011). "Mood-Linked Responses in Medial Prefrontal Cortex Predict Relapse in Patients with Recurrent Unipolar Depression". Biological Psychiatry. 70 (4): 366–372. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.03.009. ISSN 0006-3223.

- ↑ Bhagwagar, Z., Hinz, R., Taylor, M., Fancy, S., Cowen, P., Grasby, P. (September 2006). "Increased 5-HT 2A Receptor Binding in Euthymic, Medication-Free Patients Recovered From Depression: A Positron Emission Study With [ 11 C]MDL 100,907". American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (9): 1580–1587. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1580. ISSN 0002-953X.

- ↑ Meyer, J. H., McMain, S., Kennedy, S. H., Korman, L., Brown, G. M., DaSilva, J. N., Wilson, A. A., Blak, T., Eynan-Harvey, R., Goulding, V. S., Houle, S., Links, P. (January 2003). "Dysfunctional Attitudes and 5-HT2 Receptors During Depression and Self-Harm". American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (1): 90–99. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.90. ISSN 0002-953X.

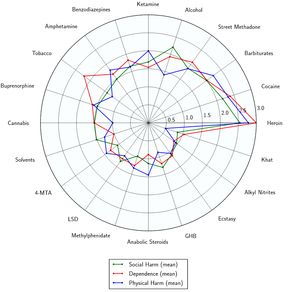

- ↑ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283

. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. Unknown parameter

. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. Unknown parameter |s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ Nutt, D., King, L. A., Saulsbury, W., Blakemore, C. (24 March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. ISSN 0140-6736.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Nichols, David E. (2004). "Hallucinogens". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 101 (2): 131–181. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.11.002. eISSN 1879-016X. ISSN 0163-7258. OCLC 04981366.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Johnson, M. W., Griffiths, R. R., Hendricks, P. S., Henningfield, J. E. (November 2018). "The abuse potential of medical psilocybin according to the 8 factors of the Controlled Substances Act". Neuropharmacology. 142: 143–166. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.05.012. ISSN 0028-3908.

- ↑ Halpern, J. H.; Pope Jr, H. G. (2003). "Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder: what do we know after 50 years?" (PDF). Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 69 (2): 109–119. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00306-X. ISSN 0376-8716. PMID 12609692.

- ↑ Lysergic acid diethylamide

- ↑ TripSit Factsheets - Mushrooms

- ↑ Unternehmensberatung, A., § 27 SMG (Suchtmittelgesetz), Unerlaubter Umgang mit Suchtgiften - JUSLINE Österreich

- ↑ All acording to articles (artigos) 2 and 33, Lei nº 11.343 of 23/8/2006, referring to numbers 160 and 161 of chart F2 (lista F2) of the Portaria SVS/MS nº 344 of 12/5/1998, last amended by Resolução de Diretoria Colegiada - RDC nº 835 of 13/12/2023, as of 29/2/2024.

- ↑ Branch, L. S. (2022), Consolidated federal laws of Canada, Controlled Drugs and Substances Act

- ↑ Anlage I BtMG - Einzelnorm

- ↑ LEGGE 16 maggio 2014, n. 79 https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2014/05/20/14G00090/sg

- ↑ Zaudējis spēku - Noteikumi par Latvijā kontrolējamajām narkotiskajām vielām, psihotropajām vielām un prekursoriem

- ↑ Legilux

- ↑ "Sidan kunde inte visas (#404) - Läkemedelsverket". 25 September 2013. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013.

- ↑ "Verordnung des EDI über die Verzeichnisse der Betäubungsmittel, psychotropen Stoffe, Vorläuferstoffe und Hilfschemikalien" (in German). Bundeskanzlei [Federal Chancellery of Switzerland]. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ↑ Participation, E., Drugs Act 2005

- ↑ FDA - Controlled Substances Act, 2017