Alcohol

Fatal overdose may occur when alcohol is combined with other depressants such as opiates, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, gabapentinoids, thienodiazepines or other GABAergic substances.[1]

It is strongly discouraged to combine these substances, particularly in common to heavy doses.

Alcohol is a Group 1 carcinogen

For roughly two decades, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) of the World Health Organization has classified alcohol as a Group 1 Carcinogen.[2] The WHO emphasizes, "there is no safe amount that does not affect health.". Alarmingly, the WHO also highlighted that nearly half of all alcohol-attributable cancers in the European Region are linked to consumption, even from "light" or "moderate" drinking.[3] |

| Summary sheet: Alcohol |

| Alcohol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Nomenclature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common names | Alcohol, Booze, Liquor, Moonshine[1], Sauce, Juice, Bevvy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Substitutive name | Ethyl alcohol, EtOH | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systematic name | Ethanol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Class Membership | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Psychoactive class | Depressant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chemical class | Alcohol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Routes of Administration | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interactions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stimulants | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cannabis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amphetamines | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AMT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MDMA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nitrous | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SSRIs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cocaine | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MAOIs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ALDH2 inhibitors | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hepatotoxic drugs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Depressants | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dissociatives | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Benzodiazepines | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DXM | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GHB | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GBL | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ketamine | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MXE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opioids | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tramadol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ethanol (also known as ethyl alcohol, ethyl hydroxide, drinking alcohol or simply alcohol) is a depressant substance of the alcohol class. It is the primary psychoactive component of alcoholic drinks, liquors and spirits; making it the second-most widely used recreational substance globally (after caffeine). The alcoholic beverage known as beer is the most widely consumed beverage in the world after water and tea. Ethanol principally acts by binding to GABA receptors in parts of the brain, but is also known to exhibit “promiscuous” pharmacological activity due to its activation of and/or interaction with various neurotransmitters and receptor sites.

Ethanol is only one of several alcohols; other alcohols such as methanol and isopropyl alcohol are significantly more toxic.[4] A mild, brief exposure to isopropyl alcohol (which is only moderately more toxic than ethanol) is unlikely to cause any serious harm, but methanol is lethal even in small quantities, as little as 10–15 milliliters (2–3 teaspoons). However, isopropyl alcohol, and ethanol, are just a few psychoactive alcohols in alcoholic drinks, and analogues. Unlike primary alcohols like ethanol, tertiary alcohols cannot be oxidized into aldehyde or carboxylic acid metabolites, which are often toxic. For example, the tertiary alcohol 2M2B is 20 times more potent than ethanol, and has been used recreationally.

The practice of consuming ethanol in the form of alcoholic drinks predates written history. Alcoholic beverages have been produced and consumed by humans since the Neolithic Era, from hunter-gatherer communities to nation-states.[5] In modern times, drinking alcohol is the most commonly used legal recreational substance in the world.[6] More than 100 countries have laws regulating its production, sale, and consumption.[7]

Subjective effects include sedation, disinhibition, anxiety suppression, empathy, affection and sociability enhancement, muscle relaxation, and euphoria. However, the degree to which these effects are present can depend somewhat on the method of production and degree of distillation. Alcoholic beverages are divided into three major classes: beers, wines, and spirits (distilled beverages).[4]

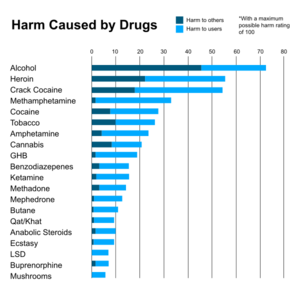

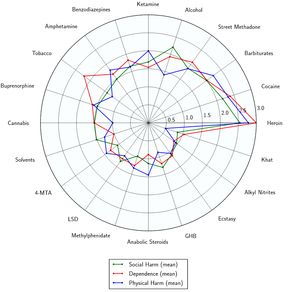

Despite sometimes being considered harmless on basis of its legality and widespread use, ethanol is capable of causing significant harm and toxicity to the user. It is considered to have moderate abuse potential and chronic use is associated with escalating tolerance, physical dependence, and addiction.[citation needed] Additionally, chronic use is associated with negative effects on the brain and other organs.[citation needed] There is also a substantial risk of fatal respiratory overdose when it is combined with other depressants (e.g. benzodiazepines, opioids). As a result, it is highly advised to use harm reduction practices if using this substance.

Uses

Recreational use

"Social drinking", also commonly referred to as "responsible drinking," refers to casual drinking in a social setting without an intent to get drunk. Good news is often celebrated by a group of people having a few drinks. For example, drinks may be served in the celebration of a birth. Buying someone a drink is a gesture of goodwill. It may be an expression of gratitude, or it may mark the resolution of a dispute.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines binge drinking as a pattern of alcohol consumption that brings a person's blood alcohol concentration (BAC) to 0.08 percent or above. This typically occurs when men consume five or more US standard drinks, or women consume four or more drinks, within about two hours. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines binge drinking slightly differently, focusing on the number of drinks consumed on a single occasion. According to SAMHSA, binge drinking is consuming five or more drinks for men, or four or more drinks for women, on the same occasion on at least one day in the past month.[8]

In countries that have a drinking culture, social stigma may cause many people not to view alcohol as a drug because it is an important part of social events. In these countries, many young binge drinkers prefer to call themselves hedonists rather than binge drinkers[9] or recreational drug users. Undergraduate students often position themselves outside the categories of "serious" or "anti-social" drinkers,[10] or "drugged" while drunk. However, about 40 percent of college students in the United States[11] could be considered alcoholics according to new criteria in DSM-5 but most college binge drinkers and drug users don't develop lifelong problems.[11][12]

In 2015, among Americans, 89% of adults had consumed alcoholic drinks at some point, 70% had drunk it in the last year, and 56% in the last month.[13]

Starting from the 2000s, the advent of a new subculture that prefers not to drink has been observed.[14]

Self-medication

Alcohol is widely available and can be used as anxiolytic to calm a bad trip for substances that don't interact with it, if better suited medications like benzodiazepines or antipsychotics are not available.

Alcohol is often used to self-medicate mental disorders but often leads to alcohol dependence.[15]

Spiritual

Spiritual use of moderate alcohol consumption is found in some religions and schools with esoteric influences, including the Hindu tantra sect Aghori, in the Sufi Bektashi Order and Alevi Jem (Alevism) ceremonies,[16] in the Rarámuri religion, in the Japanese religion Shinto,[17] by the new religious movement Thelema, in Vajrayana Buddhism, and in Haitian Vodou faith of Haiti.

History and culture

Alcohol was brewed as early as 7000 to 6650 BCE in northern China.[18] Beer was likely brewed from barley as early as the sixth century BCE in Egypt.[19] Pliny the Elder wrote about the golden age of winemaking in Rome, the second century BCE, when vineyards were planted. In vino veritas is a Latin phrase that means "in wine there is truth."

The global alcoholic beverages industry exceeded $1 trillion in 2018.[citation needed]

Religion

The relationship between alcohol and religion exhibits variations across cultures, geographical areas, and religious denominations. Some religions emphasize moderation and responsible use as a means of honoring the divine gift of life, while others impose outright bans on alcohol as a means of honoring the divine gift of life. Moreover, within the same religious tradition, there are many adherents that may interpret and practice their faith's teachings on alcohol in diverse ways. Hence, a wide range of factors, such as religious affiliation, levels of religiosity, cultural traditions, family influences, and peer networks, collectively influence the dynamics of this relationship.

The levels of alcohol use in spiritual context can be broken down into:

- Prohibition: Some religions, including Islam[20] prohibit alcohol consumption.

- Symbolic use: In some Christian denominations, the sacramental wine is alcoholic, however, only a sip is taken, and it does not raise the blood alcohol content, and other denominations are using nonalcoholic wine. See also Libation.

- Discourage consumption: Hinduism does not have a central authority which is followed by all Hindus, though religious texts generally discourage the use or consumption of alcohol.

- Spiritual: See the spiritual section.

- Recreational use: Recreational drug use of alcohol in moderation to celebrate joy, is allowed in some religions.

- Christian views on alcohol are varied. For example, in the mid-19th century, some Protestant Christians moved from a position of allowing moderate use of alcohol (sometimes called moderationism) to either deciding that not imbibing was wisest in the present circumstances (abstentionism) or prohibiting all ordinary consumption of alcohol because it was believed to be a sin (prohibitionism).[21]

- During the Jewish holiday of Purim, Jews are obligated to drink (especially Kosher wine) until their judgmental abilities become impaired according to the Book of Esther.[22][23][24] However, Purim has more of a national than a religious character.

Contraindication

In the US, alcohol is subject to the FDA drug labeling Pregnancy Category X (Contraindicated in pregnancy).

Ethanol is classified as a teratogen[25][26] -- a substance known to cause birth defects; According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), alcohol consumption by women who are not using birth control increases the risk of fetal alcohol syndrome. The CDC currently recommends complete abstinence from alcoholic beverages for women of child-bearing age who are pregnant, trying to become pregnant, or are sexually active and not using birth control.[27]

Chemistry

Fruits and nectars contain small amounts of naturally-occurring ethanol, but not enough to cause intoxication. Animals and, in rare cases, humans, can become drunk if they consume large amounts of fermented fruit where yeast fermentation has significantly increased the alcohol content. However, this is not a safe or recommended way to consume alcohol, and the amount of fruit needed would likely be impractical and unhealthy. Humans have developed fermentation and distillation techniques to create alcoholic beverages with much higher and controlled ethanol concentrations.

Ethanol is the second simplest compound of the alcohol family. The structure of ethanol is comprised of a chain of two carbon atoms, known as ethane, with a hydroxyl (-OH) functional group attached to form an alcohol.

Alcoholic drinks contain ethanol but also smaller amounts of several other alcohols that act as psychoactive drugs with different degrees of potency and effects and also contribute to the color, odor, and flavor of beverages.

The Lucas test in alcohols is a test to differentiate between primary, secondary, and tertiary alcohols.

Psychoactive alcohols found in drinks

In general, the labels of beverages containing significant alcohol by volume (ABV) must state the actual alcoholic strength (i.e., "x% alc. by vol."), this helps prevent people from unknowingly driving under the influence of alcohol or engaging in other risky behavior without awareness of their level of intoxication. The term alcohol principally refers to the primary alcohol ethanol, the dominating alcohol in alcoholic beverages that are subject to alcohol laws including alcohol monopoly and alcohol taxes in countries that regulate their sale and consumption. However, since then other alcohols have been identified, including 1-Propanol found in Jamaican rum, which contributes an estimated 21% to the total alcohol intoxication in 40% ABV rum.[28] A tertiary alcohol named tert-Amyl alcohol (2M2B) has been identified in beer (the third-most popular drink overall, after drinking water and tea[29]). tert-Amyl alcohol is sometimes used as a recreational drug.[30]

Some beverages such as rum, whisky (especially Bourbon whiskey), incompletely rectified vodka (e.g. Siwucha), and traditional ales and ciders are expected to contain non-hazardous[clarification needed] aroma alcohols as part of their flavor profile.[28] European legislation demands a minimum content of higher alcohols[clarification needed] in certain distilled beverages (spirits) to give them their expected distinct flavour.[31]

Ethanol analogues

Alcohols are a highly-diverse chemical class of organic compounds that contain one or more hydroxyl functional groups (-OH) bound to a carbon atom. Alcohols are classified into primary, secondary (sec-, s-), and tertiary (tert-, t-), based upon the number of carbon atoms connected to the carbon atom that bears the hydroxyl functional group.

Ethanol has a variety of structural analogs, many of which have similar effects.

In the alcoholic drinks industry, congeners are substances produced during ethanol fermentation. These substances include small amounts of more potent chemicals such as occasionally desired other alcohols, like 1-Propanol, 2-Methyl-1-butanol (2M1B), 2-Methyl-1-propanol (2M1P), and 3-methyl-1-butanol (3M1B), but also compounds that are never desired such as acetone, acetaldehyde, and glycols. Congeners are responsible for most of the taste and aroma of distilled alcoholic drinks and contribute to the taste of non-distilled drinks.[36]

Methanol (methyl alcohol, wood alcohol) and isopropanol (isopropyl alcohol, rubbing alcohol) are toxic and are not safe for human consumption.[4] Methanol is the most toxic alcohol; the toxicity of isopropanol lies between that of ethanol and methanol, and is about twice that of ethanol.[37] In general, higher alcohols are less toxic.[37] n-Butanol is reported to produce similar effects to those of ethanol and relatively low toxicity (one-sixth of that of ethanol in one rat study).[38][39] However, its vapors can produce eye irritation and inhalation can cause pulmonary edema.[37] Acetone (propanone) is a ketone rather than an alcohol, and is reported to produce similar toxic effects; it can be extremely damaging to the cornea.[37]

The tertiary alcohol tert-Amyl alcohol (TAA), also known as 2-methylbutan-2-ol (2M2B), has a history of use as a hypnotic and anesthetic, as do other tertiary alcohols such as methylpentynol, ethchlorvynol, and chloralodol. Unlike primary alcohols like ethanol, these tertiary alcohols cannot be oxidized into aldehyde or carboxylic acid metabolites, which are often toxic, and for this reason, these compounds are safer in comparison.[35] Also, surrogate alcohol products are not subject to alcohol tax. However, their use has phased out in response to newer drugs with far more favorable safety profiles like chloral hydrate, paraldehyde, and many volatile and inhalational anesthetics (e.g., diethyl ether, and isoflurane).

Pharmacology

Ethanol in low doses causes euphoria, reduced anxiety, increased sociability and enthusiasm, with notably higher doses causing alcohol intoxication (drunkenness), stupor, unconsciousness, severe motor control loss, and a general depression (inhibition) of central nervous system’s functions. Long-term use can lead to alcohol abuse, physical dependence, or “alcoholism” (which is regarded as a fairly loose term).

Alcohol can be addictive to humans and can result in alcohol tolerance (decreased sensitivity to the drug), alcohol withdrawal syndrome (drug dependence) or alcoholism-related health problems. It has been known to have a number of adverse effects on health. The drug has been adjudged to be neurotoxic when consumed in sufficient quantities.[40][41] In high doses or overdoses, alcohol may cause a loss of consciousness or, in severe cases, death. It is a causative factor for many traffic accidents and vehicular fatalities due to intoxicated driving. It has also been implicated in a sizable percentage of violent crime in society.

In the past, alcohol was believed to be a non-specific pharmacological agent affecting many neurotransmitter systems in the brain.[42] Although this notion still bears some degree of truth, further studies conducted into its molecular pharmacology in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of its precise pharmodynamics has demonstrated that alcohol has only a few primary targets, particularly through (enhancement/facilitation of) certain GABA receptors. However, its overall pharmacological profile and range of effects can still be considered facilitatory in some systems (such as GABA), while being inhibitory in others.

Such enhancements of certain neurotransmitter systems are listed below, where ethanol (alcohol) has been known to functions as a:

- GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulator (primarily of δ subunit-containing receptors)[43] In a fashion similar to benzodiazepines and barbiturates, an enhancement of the inhibitory system known as GABA induces neurological, as well as broader physiological inhibitions. This enhances the behavioral inhibitory centers, therefore slowing down the processing of novel information from the senses, inhibiting various types of cognitive thought processes, as well as generally inducing a suppression of both normal somatic and cognitive functions. However, the drug’s typical cooccurring modulations of other neurotransmitter systems, especially in modest dosages can appear to somewhat; or even sufficiently counter or at least mitigate some of these cognitive suppressions thus making it relatively unique when compared to other GABAergic drugs that almost exclusively lead to neurological/physiological suppressions regardless of dose, as opposed to alcohol’s “balance beam” form of neurological activity.

- 5-HT3 receptor agonism[44]

- Glycine receptors

- Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors[45]

- Adenosine:[46]Ethanol blocks adenosine uptake via inhibiting the nucleoside transport system in bronchial epithelial cells. Inhibition of adenosine uptake by ethanol leads to an increased extracellular adenosine accumulation, influencing the effect of adenosine at the epithelial cell surface, which may alter airway homeostasis.

Among the neurotransmitters which are suppressed/inhibited however, these include:

- Glutamate[47]: By making this excitatory neurotransmitter less effective, certain neurophysiological processes become further inhibited. Alcohol does this by interacting with the receptors on the receiving cells within these pathways and blocking glutamate from binding to NMDA receptors which triggers particular electrochemical signals.

- Dihydropyridine[48]: The result of these direct influences leads is a wave of further indirect (or secondary) effects involving a variety of other neurotransmitter and neuropeptide systems, thus seeming to lead to the characteristic behavioral and symptomatic effects observed within individuals affected by alcohol intoxication.[42] It's worth noting however, that in terms of how these processes directly result in the experience of alcohol’s fairly specific set of subjective effects, as well as the exact underlying causal mechanisms behind them still remains largely unknown beyond mere speculation by researchers through various interpretations of the currently available, albeit still limited pharmacological data for the drug.

Onset

The onset varies depends on the type of alcoholic drink:[49]

- Vodka/tonic: 36 ± 10 minutes

- Wine: 54 ± 14 minutes

- Beer: 62 ± 23 minutes

Also, carbonated alcoholic drinks seem to have a shorter onset compare to flat drinks in the same volume. One theory is that carbon dioxide in the bubbles somehow speeds the flow of alcohol into the intestines.[50]

Types

Drinking alcohols can be consumed either as:

- Alcoholic drink: An alcoholic drink is commonly known as alcohol and causing the characteristic effects of alcohol intoxication or "drunkenness". Alcoholic drinks are typically divided into three classes—beers, wines, and spirits—and typically contain between 3% and 40% alcohol by volume. Also, alcoholic drinks typically contain 3%–40% ethyl alcohol (ethanol), but beer contain 0.07% 2M2B which is 20 times more potent, thus contributing to 28% (0.07×20÷5 ) of the alcohol intoxication, Jamaican rum contains 2.8% 1-propanol which is 3 times more potent, thus contributing to 21% (2,8×3÷40) of the alcohol intoxication (see table).

- Rectified spirits: Rectified spirit is also known as neutral spirits, rectified alcohol. In its undiluted form, it contains at least 95% alcohol by volume (ABV) (190 US proof) in the United States, or at least 96% ABV in the European Union,[51] respectively. The purity of rectified spirit has a practical limit of 97.2% ABV (95.6% by mass)[52] Other alcohols than ethanol are produced for industrial use as solvents (eg 2M2B and 1-Propanol) but have been used as novel drugs (if not denatured) and are usually not subject to alcohol laws like alcohol tax and legal drinking age.

- Hazardous alcohols like methanol (used in denatured alcohol and wood alcohol) and isopropanol (many varieties of rubbing alcohol) are potentially lethal.[4]

Preparation

Recipes and preparation methods

Subjective effects

Disclaimer: The effects listed below cite the Subjective Effect Index (SEI), an open research literature based on anecdotal user reports and the personal analyses of PsychonautWiki contributors. As a result, they should be viewed with a healthy degree of skepticism.

It is also worth noting that these effects will not necessarily occur in a predictable or reliable manner, although higher doses are more liable to induce the full spectrum of effects. Likewise, adverse effects become increasingly likely with higher doses and may include addiction, severe injury, or death ☠.

Physical effects

-

- Neurotoxicity[53][54]

- Sedation & Stimulation - This effect manifests itself as an increase in energy and desire to do certain activities in moderate doses, whereas low or high doses can cause the user to feel sedated and sleepy

- Muscle relaxation

- Pain relief

- Physical euphoria

- Appetite enhancement

- Motor control loss

- Body odor alteration - This effect is present at all dosages, and becomes more pronounced the higher the dosage is. This results from the liver's inability to eliminate all alcohol present within one's system. Alcohol not eliminated by the liver will then be eliminated via the kidneys, lungs, and through perspiration (sweating), the latter of which causes a change in body odor, as well as increased perspiration.[55]

- Increased blood pressure[citation needed]

- Increased perspiration[citation needed]

- Nausea

- Dehydration

- Difficulty urinating & Frequent urination

- Dizziness

- Headaches

- Temperature regulation suppression

- Increased bodily temperature or Decreased bodily temperature - It is a common myth that alcohol intoxication can lower the chances of experiencing hypothermia when, in fact, it actually increases the chances of hypothermia in part due to temperature regulation suppression. Even small amounts of alcohol can begin to slow down the mechanisms that help maintain a normal body core temperature.[citation needed]

- Respiratory depression - This effect becomes more pronounced at heavier dosages, and may lead or contribute to a loss of consciousness ("blacking out"), or in extreme cases, death.

- Skin flushing

- Tactile suppression - This effect is not usually as pronounced as it is with substances such as ketamine or PCP, but can still manifest itself in varying degrees of intensity.

- Temporary erectile dysfunction

Visual effects

-

- Acuity suppression

- Double vision - This effect increases in proportion to dose and can make driving or operating machinery impossible.

- Pattern recognition suppression

- After images - This effect may present itself at higher doses.

Cognitive effects

-

- Analysis suppression

- Anxiety suppression

- Disinhibition

- Cognitive euphoria

- Compulsive redosing

- Creativity suppression

- Delusions of sobriety - This is the false belief that one is perfectly sober despite obvious evidence to the contrary such as severe cognitive impairment and an inability to fully communicate with others.

- Depression

- Ego inflation

- Empathy, affection, and sociability enhancement

- Emotion enhancement

- Focus suppression

- Increased music appreciation

- Increased libido

- Information processing suppression

- Language suppression

- Memory suppression

- Sleepiness - This effect is experienced almost exclusively in low or high dosages. Small doses of alcohol can cause many users to feel anywhere from mildly to extremely tired whereas moderate doses can actually lead to feelings of stimulation and wakefulness. On very high amounts, however, chances of the individual becoming unconscious are much greater.

- Suggestibility suppression

- Irritability

- Thought deceleration

- Thought disorganization

Auditory effects

-

- Suppressions or Enhancements - While alcohol is technically capable of both enhancing and suppressing auditory stimuli, it generally suppresses it, although some users note that sounds appear enhanced and markedly louder while under the influence.

After effects

-

The effects which occur during the offset of an alcohol intoxication generally feel negative and uncomfortable in comparison to the effects which occurred during its peak. This is often referred to as a "comedown" or "hangover" and occurs mainly because of dehydration in part due to diuresis. Its effects commonly include:

- Anxiety

- Delirium tremens

- Appetite suppression

- Cognitive fatigue and Physical fatigue

- Dehydration

- Nausea

- Headaches

- Information processing suppression

- Sleep paralysis - Some users experience sleep paralysis after alcohol consumption; it is usually associated with consistent usage.

- Thought deceleration

Experience reports

There are currently 1 experience reports describing the effects of this substance in our experience index. You can also submit your own experience report using the same link.

Additional experience reports can be found here:

Medical uses

Alcohols, in various forms, are used within medicine as an antiseptic, disinfectant, and antidote.[56] Aside from these uses, alcohol has no other well-accepted medical uses,[57] the therapeutic index of ethanol is only 10:1.[58]

Applied to the skin it is used to disinfect skin before a needle injection and before surgery.[59]

Taken by mouth or intravenously it is used to treat methanol or ethylene glycol toxicity when fomepizole is not available.[56] Ethanol acts as a competitive inhibitor with other alcohols for the alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme, lessening metabolism into toxic aldehyde and carboxylic acid derivatives,[60] and reducing one of the more serious toxic effect of the glycols to crystallize in the kidneys.

Toxicity and harm potential

The sensible use of alcohol in the short term is extremely unlikely to have any positive or detrimental effects on one's physical health. However, despite the widespread use and alcohol's legality in most countries, many medical sources tend to describe any level of alcohol intoxication as a form of poisoning due to ethanol's damaging effects on the body in large doses.

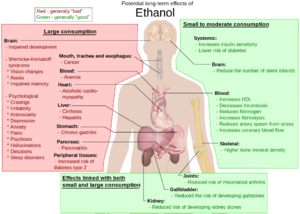

The long-term effects of alcohol consumption range from cardioprotective health benefits for low to moderate alcohol consumption in industrialized societies with higher rates of cardiovascular disease[62][63] to severe detrimental effects in cases of chronic alcohol abuse.[64]

High levels of alcohol consumption are associated with an increased risk of alcoholism, malnutrition, chronic pancreatitis, alcoholic liver disease, and cancer. In addition, damage to the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system can occur from chronic alcohol abuse.[65][66] The long-term use of alcohol is capable of damaging nearly every organ and system in the body.[67] The developing adolescent brain is particularly vulnerable to the toxic effects of alcohol.[68] In addition, the developing fetal brain is also vulnerable, and fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) may result if pregnant mothers consume alcohol.

Alcoholic drinks are classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as a Group 1 carcinogen (carcinogenic to humans). IARC classifies alcoholic drink consumption as a cause of cancer for female breast, colorectum, larynx, liver, esophagus, oral cavity, and pharynx; and as a probable cause of pancreatic cancer.[69] Alcohol in soft drinks is absorbed faster than alcohol in non-carbonated drinks.[70]

Recommended maximum intake of alcoholic beverages

According to The World Health Organization, The World Heart Federation and Nordic Nutrition there is no safe amount that does not affect health.[71][72][73][74]

According to the WHO nearly half of all alcohol-attributable cancers in the WHO European Region are linked to alcohol consumption, even from "light" or "moderate" drinking – "less than 1.5 litres of wine or less than 3.5 litres of beer or less than 450 millilitres of spirits per week".[3]

Short-term effects

Wine, beer, distilled spirits, and other alcoholic drinks contain ethyl alcohol and alcohol consumption has short-term psychological and physiological effects on the user. Different concentrations of alcohol in the human body have different effects on a person. The effects of alcohol depend on the amount an individual has drunk, the percentage of alcohol in the wine, beer or spirits and the timespan that the consumption took place, the amount of food eaten and whether an individual has taken other prescription, over-the-counter or street drugs, among other factors.

Drinking enough to cause a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.03%-0.12% typically causes an overall improvement in mood and possible euphoria, increased self-confidence and sociability, decreased anxiety, an alcohol flush reaction (red appearance in the face) and impaired judgment and fine muscle coordination. A BAC of 0.09% to 0.25% causes lethargy, sedation, balance problems and blurred vision. A BAC from 0.18% to 0.30% causes profound confusion, impaired speech (e.g., slurred speech), staggering, dizziness and vomiting. A BAC from 0.25% to 0.40% causes stupor, unconsciousness, anterograde amnesia, vomiting (death may occur due to inhalation of vomit (pulmonary aspiration) while unconscious) and respiratory depression (potentially life-threatening). A BAC from 0.35% to 0.80% causes a coma (unconsciousness), life-threatening respiratory depression and possibly fatal alcohol poisoning. As with all alcoholic drinks, drinking while driving, operating an aircraft or heavy machinery increases the risk of an accident; many countries have penalties against drunk driving.

Ethanol is often used to facilitate sexual assault or rape.[75][76] It is the most commonly used date rape drug.[77]

Rehydration therapy before going to bed or during hangover may relieve dehydration-associated symptoms such as thirst, dizziness, dry mouth, and headache.[78][79][80][81][82][83]

Alcohol intoxication

Lethal dosage

Death from ethanol consumption is possible when blood alcohol levels reach 0.4%. A blood level of 0.5% or more is commonly fatal. Levels of even less than 0.1% can cause intoxication with unconsciousness often occurring at 0.3–0.4%.[84]

It is strongly recommended that one use harm reduction practices when using this substance.

Long-term effects

The main active ingredient of wine, beer and distilled spirits is alcohol. Drinking small quantities of alcohol (less than one drink in women and two in men per day) is debated to decreased the risk of heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, and early death.[86] Drinking more than this amount, however, increases the risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, and stroke.[87] The risk is greater in younger people due to binge drinking which may result in violence or accidents.[87] About 3.3 million deaths (5.9% of all deaths) are believed to be due to alcohol each year.[13] Alcoholism reduces a person's life expectancy by around ten years[88] and alcohol use is the third leading cause of early death in the United States.[87] No professional medical association recommends that people who are nondrinkers should start drinking wine.[87][89]

Most people are under the influence of sedative-hypnotic drugs (such as alcohol or benzodiazepines) when they die by suicide,[90] with alcoholism present in between 15% and 61% of cases.[91] Countries that have higher rates of alcohol use and a greater density of bars generally also have higher rates of suicide.[92] About 2.2–3.4% of those who have been treated for alcoholism at some point in their life die by suicide.[92] Alcoholics who attempt suicide are usually male, older, and have tried to take their own lives in the past.[91] In adolescents who misuse alcohol, neurological and psychological dysfunctions may contribute to the increased risk of suicide.[93]

Another long-term effect of alcohol usage, when also used with tobacco products, is alcohol acting as a solvent, which allows harmful chemicals in tobacco to get inside the cells that line the digestive tract. Alcohol slows these cells' healing ability to repair the damage to their DNA caused by the harmful chemicals in tobacco. Alcohol contributes to cancer through this process.[94]

While lower quality evidence suggests a cardioprotective effect, no controlled studies have been completed on the effect of alcohol on the risk of developing heart disease or stroke. Excessive consumption of alcohol can cause liver cirrhosis and alcoholism.[95] The American Heart Association "cautions people NOT to start drinking ... if they do not already drink alcohol. Consult your doctor on the benefits and risks of consuming alcohol in moderation."[96]

Tolerance and addiction potential

The chronic use of this compound can be considered extremely addictive with a high potential for abuse and is capable of causing psychological dependence among certain users. When addiction has developed, cravings and withdrawal effects may occur if a person suddenly stops their usage.

Alcohol tolerance

Tolerance to many of the effects of alcohol develops with prolonged and repeated use. This results in users having to administer increasingly large doses to achieve the same effects. After that, it takes about 3 - 7 days for the tolerance to be reduced to half and 1 - 2 weeks to be back at baseline (in the absence of further consumption). Alcohol presents cross-tolerance with all GABAgenic depressants, meaning that after the consumption of alcohol all depressants will have a reduced effect.

Alcoholism

Alcoholism, also known as alcohol use disorder (AUD), is a broad term for any drinking of alcohol that results in mental or physical health problems.[97] It was previously divided into two types: alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence.[98][99] In a medical context, alcoholism is said to exist when two or more of the following conditions is present: a person drinks large amounts over a long time period, has difficulty cutting down, acquiring and drinking alcohol takes up a great deal of time, alcohol is strongly desired, usage results in not fulfilling responsibilities, usage results in social problems, usage results in health problems, usage results in risky situations, Alcohol withdrawal syndrome|withdrawal occurs when stopping, and alcohol tolerance has occurred with use.[98] Risky situations include driving under the influence|drinking and driving or having unsafe sex among others.[98] Alcohol use can affect all parts of the body but particularly affects the brain, heart, liver, pancreas, and immune system.[100][101] This can result in mental illness, Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome, an arrhythmia|irregular heart beat, cirrhosis|liver failure, and an increase in the risk of cancer, among other diseases.[100][101] Drinking during pregnancy can cause damage to the baby resulting in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.[102] Generally women are more sensitive to alcohol's harmful physical and mental effects than men.[103]

Heavy alcohol use is defined differently by various health organizations. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) provides gender-specific guidelines for heavy drinking. According to NIAAA, men who consume five or more US standard drinks in a single day or 15 or more drinks within a week are considered heavy drinkers. For women, the threshold is lower, with four or more drinks in a day or eight or more drinks per week classified as heavy drinking. In contrast, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) takes a different approach to defining heavy alcohol use. SAMHSA considers heavy alcohol use to be engaging in binge drinking behaviors on five or more days within a month. This definition focuses more on the frequency of excessive drinking episodes rather than specific drink counts.[8]

Chronic excess alcohol intake can lead to a wide range of neuropsychiatric or neurological impairment, cardiovascular disease, liver disease, and malignant neoplasms. The psychiatric disorders which are associated with alcoholism include major depression, dysthymia, mania, hypomania, panic disorder, phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, personality disorders, schizophrenia, suicide, neurologic deficits (e.g., impairments of working memory, emotions, executive functions, visuospatial abilities, gait, and balance) and brain damage. Alcohol dependence is associated with hypertension, coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, and also cancers of the respiratory system, the digestive system, liver, breast, and ovaries. Heavy drinking is associated with liver disease, such as cirrhosis.[104]

Withdrawals

When physical dependence has developed, withdrawal symptoms may occur if a person suddenly stops their usage. The severity of withdrawal can vary from mild symptoms such as sleep disturbances and anxiety to severe and life-threatening symptoms such as delirium, hallucinations, and autonomic instability.

Withdrawal usually begins 6 to 24 hours after the last drink.[105][106] To be classified as alcohol withdrawal syndrome, patients must exhibit at least two of the following symptoms: increased hand tremors, insomnia, nausea or vomiting, transient hallucinations (auditory, visual or tactile), psychomotor agitation, anxiety, tonic-clonic seizures, and autonomic instability.[107]

The severity of symptoms is dictated by a number of factors, the most important of which is a degree of alcohol intake, length of time the individual has been using alcohol, and previous history of alcohol withdrawal.[107] Symptoms are also grouped together and classified:

- Alcohol hallucinosis: Patients have transient visual, auditory, or tactile hallucinations but are otherwise clear.[107]

- Withdrawal seizures: Seizures occur within 48 hours of alcohol cessation and occur either as a single generalized tonic-clonic seizure or as a brief episode of multiple seizures.[108]

- Delirium tremens: Hyperadrenergic state, disorientation, tremors, diaphoresis, impaired attention/consciousness, and visual and auditory hallucinations[107] usually occur 24 to 72 hours after alcohol cessation. Delirium tremens is the most severe form of withdrawal and occurs in 5 to 20% of patients experiencing detoxification and 1/3 of patients experiencing withdrawal seizures.[108]

Withdrawal symptoms and management

Signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal occur primarily in the central nervous system. The severity of withdrawal can vary from mild symptoms such as sleep disturbances and anxiety to severe and life-threatening symptoms such as delirium, hallucinations, and autonomic instability.

Withdrawal usually begins 6 to 24 hours after the last drink.[105] It can last for up to one week.[106] To be classified as alcohol withdrawal syndrome, patients must exhibit at least two of the following symptoms: increased hand tremor, insomnia, nausea or vomiting, transient hallucinations (auditory, visual or tactile), psychomotor agitation, anxiety, tonic-clonic seizures, and autonomic instability.[107]

The severity of symptoms is dictated by a number of factors, the most important of which is degree of alcohol intake, length of time the individual has been using alcohol, and the previous history of alcohol withdrawal.[107] Symptoms are also grouped together and classified:

- Alcohol hallucinosis: patients have transient visual, auditory, or tactile hallucinations, but are otherwise clear.[107]

- Withdrawal seizures: seizures occur within 48 hours of alcohol cessations and occur either as a single generalized tonic-clonic seizure or as a brief episode of multiple seizures.[108]

- Delirium tremens: hyperadrenergic state, disorientation, tremors, diaphoresis, impaired attention/consciousness, and visual and auditory hallucinations.[107] This usually occurs 24 to 72 hours after alcohol cessation. Delirium tremens is the most severe form of withdrawal and occurs in 5 to 20% of patients experiencing detoxification and 1/3 of patients experiencing withdrawal seizures.[108]

Benzodiazepines are effective for the management of symptoms as well as the prevention of seizures.[109] In those with severe symptoms inpatient care is often required. In those with lesser symptoms treatment at home may be possible with daily visits with a health care provider.[105]

Patients in alcohol withdrawal are typically also given thiamine and folic acid. These vitamins are not treatments for withdrawal per se. Instead, long-term consumption of alcohol tends to deplete these nutrients and lead to additional neurological issues such as Wernicke encephalopathy.[105]

Anti-addictive drugs

- Disulfiram-like drugs: disulfiram, calcium carbimide, cyanamide; see Wikipedia page for a somewhat complete list. This class of drugs enhance subjective unpleasantness of alcohol by inhibiting ALDH2, causing accumulation of acetaldehyde. This same mechanism also enhances the physical harm of alcohol.

- Ibogaine - Rezvani reported reduced alcohol dependence in three strains of "alcohol preferring" rats in 1995.[110]

- Naltrexone - Naltrexone has been best studied as a treatment for alcoholism. Naltrexone has been shown to decrease the amount and frequency of drinking. It does not appear to change the percentage of people drinking. Its overall benefit has been described as "modest".The Sinclair method is a method of using opiate antagonists such as naltrexone to treat alcoholism. The person takes the medication about an hour (and only then) before drinking to avoid side effects that arise from chronic use. The opioid antagonist blocks the positive-reinforcement effects of alcohol and allows the person to stop or reduce drinking.

Interactions

Dangerous interactions

Ethanol can intensify the sedation caused by other central nervous system depressant drugs such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines, opioids, nonbenzodiazepines/Z-drugs (such as zolpidem and zopiclone), antipsychotics, sedative antihistamines, and certain antidepressants.[84] It interacts with cocaine in vivo to produce cocaethylene, another psychoactive substance.[111] Ethanol enhances the bioavailability of methylphenidate (elevated plasma dexmethylphenidate).

Warning: Many psychoactive substances that are reasonably safe to use on their own can suddenly become dangerous and even life-threatening when combined with certain other substances. The following list provides some known dangerous interactions (although it is not guaranteed to include all of them).

Always conduct independent research (e.g. Google, DuckDuckGo, PubMed) to ensure that a combination of two or more substances is safe to consume. Some of the listed interactions have been sourced from TripSit.

- Depressants (1,4-Butanediol, 2M2B, alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, GHB/GBL, methaqualone, opioids) - This combination potentiates the muscle relaxation, amnesia, sedation, and respiratory depression caused by one another. At higher doses, it can lead to a sudden, unexpected loss of consciousness along with a dangerous amount of depressed respiration. There is also an increased risk of suffocating on one's vomit while unconscious. If nausea or vomiting occurs before a loss of consciousness, users should attempt to fall asleep in the recovery position or have a friend move them into it.

- Dissociatives - This combination can unpredictably potentiate the amnesia, sedation, motor control loss and delusions that can be caused by each other. It may also result in a sudden loss of consciousness accompanied by a dangerous degree of respiratory depression. If nausea or vomiting occurs before consciousness is lost, users should attempt to fall asleep in the recovery position or have a friend move them into it.

- Stimulants - Stimulants mask the sedative effect of depressants, which is the main factor most people use to gauge their level of intoxication. Once the stimulant effects wear off, the effects of the depressant will significantly increase, leading to intensified disinhibition, motor control loss, and dangerous black-out states. This combination can also potentially result in severe dehydration if one's fluid intake is not closely monitored. If choosing to combine these substances, one should strictly limit themselves to a pre-set schedule of dosing only a certain amount per hour until a maximum threshold has been reached.

- Cannabis - In combination with cannabis, ethanol increases plasma tetrahydrocannabinol levels, which suggests that ethanol may increase the absorption of tetrahydrocannabinol.[113] It is recommended that users who wish to combine these two substances start by consuming cannabis first as this reduces the chances of experiencing nausea, dizziness and double vision.

- Amphetamines - Drinking on stimulants is risky because the sedative effects of the alcohol are reduced, and these are what the body uses to gauge drunkenness. This typically leads to excessive drinking with greatly reduced inhibitions, high risk of liver damage and increased dehydration. They will also allow you to drink past a point where you might normally pass out, increasing the risk. If you do decide to do this then you should set a limit of how much you will drink each hour and stick to it, bearing in mind that you will feel the alcohol and the stimulant less. Extended release formulations may severely impede sleep, further worsening the hangover.

- AMT - aMT has a broad mechanism of action in the brain and so does alcohol so the combination can be unpredictable

- MDMA - Both MDMA and alcohol cause dehydration. Approach this combination with caution, moderation and sufficient hydration. More than a small amount of alcohol will dull the euphoria of MDMA

- Nitrous - Both substances potentiate the ataxia and sedation caused by the other and can lead to unexpected loss of consciousness at high doses. While unconscious, vomit aspiration is a risk if not placed in the recovery position. Memory blackouts are likely.

- SSRIs - Alcohol may potentiate some of the pharmacologic effects of CNS-active agents. Use in combination may result in additive central nervous system depression and/or impairment of judgment, thinking, and psychomotor skills."]

- Cocaine - Drinking on stimulants is risky because the sedative effects of the alcohol are reduced, and these are what the body uses to gauge drunkenness. This typically leads to excessive drinking with greatly reduced inhibitions, high risk of liver damage and increased dehydration. They will also allow you to drink past a point where you might normally pass out, increasing the risk. If you do decide to do this then you should set a limit of how much you will drink each hour and stick to it, bearing in mind that you will feel the alcohol less. Cocaine is potentiated somewhat by alcohol because of the formation of cocaethylene.

- MAOIs - Tyramine found in many alcoholic beverages can have dangerous reactions with MAOIs, causing an increase in blood pressure.

- PCP - Details of this combination are not well understood but PCP generally interacts in an unpredictable manner.

- Benzodiazepines - Ethanol ingestion may potentiate the CNS effects of many benzodiazepines. The two substances potentiate each other strongly and unpredictably, very rapidly leading to unconsciousness. While unconscious, vomit aspiration is a risk if not placed in the recovery position. Blacking out and memory loss is almost certain.

- DXM - Both substances potentiate the ataxia and sedation caused by the other and can lead to unexpected loss of consciousness at high doses. Place affected patients in the recovery position to prevent vomit aspiration from excess. Additionally, CNS depression can lead to difficulty breathing. Avoid on anything higher than 1st plateau.

- GHB/GBL - Even in very low doses this combination rapidly leads to memory loss, severe ataxia and unconsciousness. There is a high risk of vomit aspiration while unconscious.

- Ketamine - Both substances cause ataxia and bring a very high risk of vomiting and unconsciousness. If the user falls unconscious while under the influence there is a severe risk of vomit aspiration if they are not placed in the recovery position.

- MXE - There is a high risk of memory loss, vomiting and severe ataxia from this combination.

- Opioids - Both substances potentiate the ataxia and sedation caused by the other and can lead to unexpected loss of consciousness at high doses. Place affected patients in the recovery position to prevent vomit aspiration from excess. Memory blackouts are likely

- Tramadol - Heavy CNS depressants, risk of seizures. Both substances potentiate the ataxia and sedation caused by the other and can lead to unexpected loss of consciousness at high doses. Place affected patients in the recovery position to prevent vomit aspiration from excess. Memory blackouts are likely.

Non-psychoactive medicine interactions:

- ALDH2 inhibitors - A number of drugs are "disulfiram-like": they inhibit ALDH2, which breaks down the acetaldehyde, a toxic intermediate in the breakdown of alcohol. The result is a highly unpleasant and physically dangerous reaction on the consumption of alcohol, with symptoms such as vomiting, nausea, and shortness of breath.[114][115][116] Disulfiram, a drug of this class, has intentionally been used as an aversive aid for discontinuing alcohol. Other drugs with a similar activity are:[117]

- Disulfiram-like antibiotics: The list of antibiotics with a disulfiram-like action has been historically overinflated. Antibiotics with evidence of having this activity include cefamandole, cefmetazole, cefoperazone, cefotetan, and ceftriaxone. The unifying property is the inclusion of either a MTT or MTDT sidechain.[117] Latamoxef (moxalactam) has the same sidechain and should also be avoided. This side chain may also inhibit the body's vitamin K system independently of alcohol.[118]

- Acetaldehyde is not only acutely toxic, but also carcinogenic in humans. Alcoholics with a genetic ALDH2 deficiency have higher chances of upper digestive tract cancer.[119]

- Hepatotoxic drugs - Some hepatotoxic drugs, specifically ketoconazole, griseofulvin, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide, cause additive hepatotoxicity when consumed with alcohol. Avoid this combination to reduce liver damage.[117]

- Alcohol reduces the efficacy of some antibiotics. Chronic alcoholics break down doxycycline much faster, requiring increased dosing frequency. Alcohol delays the absorption of erythromycin, reducing its AUC. Avoid taking alcohol with these drugs to maintain their efficacy.[117]

Alcohol induced dose dumping (AIDD)

Alcohol may be dangerous to combine with modified-release dosage medications.

This dose dumping effect is an unintended rapid release of large amounts of a given drug, when administered through a modified-release dosage while co-ingesting ethanol.[120] This is considered a pharmaceutical disadvantage due to the high risk of causing drug-induced toxicity by increasing the absorption and serum concentration above the therapeutic window of the drug. The best way to prevent this interaction is by avoiding the co-ingestion of both substances or using specific controlled-release formulations that are resistant to AIDD.

Disease interactions

Alcohol is contraindicated in people with hepatic disease, gastrointestinal ulcer, cardiac or skeletal myopathy, pregnancy, and individuals previously addicted to ethanol.[121]

Gastrointestinal diseases

Alcohol stimulates gastric juice production, even when food is not present, and as a result, its consumption will stimulate acidic secretions normally intended to digest protein molecules. Consequently, excess acidity may harm the inner lining of the stomach. The stomach lining is normally protected by a mucosal layer which prevents the stomach from essentially digesting itself. However, in patients who have peptic ulcer disease (PUD), this mucosal layer is broken down. PUD is commonly associated with the bacteria H. pylori. H. pylori secrete a toxin that weakens the mucosal wall, which as a result leads to acid and protein enzymes penetrating the weakened barrier. Because alcohol stimulates the stomach to secrete acid, a person with PUD should avoid drinking alcohol on an empty stomach. Drinking alcohol would cause more acid release which would further damage the already-weakened stomach wall.[122] Complications of this disease could include burning pain in the abdomen, bloating and in severe cases, the presence of dark black stools indicate internal bleeding.[123] A person who drinks alcohol regularly is strongly advised to reduce their intake to prevent PUD aggravation.[123]

Allergic-like reactions

Ethanol-containing beverages can cause skin problems and bronchoconstriction in patients with a history of asthma. These reactions occur within 1–60 minutes of ethanol ingestion.[124] A deficiency of ALDH2 increase the likelihood of such events.[125]

ALDH2 deficiency

About 50% of East Asians have a genetic deficiency of the ALDH2 enzyme, causing the accumulation of toxic acetaldehyde even without the ingestion of disulfiram-like drugs. The symptoms are similar: vomiting, nausea, and shortness of breath.[125] There's also increased flushing, the so-called "Asian flush".[124]

Legal status

|

This legality section is a stub. As such, it may contain incomplete or wrong information. You can help by expanding it. |

Alcoholic beverages are legally consumed in most countries around the world. More than 100 countries have laws regulating their production, sale, and consumption.[7] In particular, such laws often specify the legal drinking age, which usually varies between 16 and 25 years (sometimes depending on the type of drink). Some countries do not have a legal drinking or purchasing age but most set the age at 18 years.[7]

Standard drink

The definition of a standard drink varies between countries. However, a standard drink of 10 g ethanol, which is used in the WHO AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test)'s questionnaire form example, have been adopted by more countries than any other amount.[126] 10 grams ethanol is equivalent to 12.7 millilitres.

Dosage calculation

Math to calculate the quantity needed: Desired ethanol dose (converted from grams to millitires first) divided by the ethanol concentration of the beverage. For example, if you want to consume 25 g (a common dose) from an alcohol beverage with 5% alcohol by volume:

- Convert 25 g ethanol to millilitres: 25 g x 1.27 mL = 31.75

- 31.75 mL / 5% = 31.75/0.05 = 635 mL

See also

External links

- Alcohol (drug) (Wikipedia)

- Alcohols (medicine) (Wikipedia)

- Alcoholic drink (Wikipedia)

- Moonshine (Wikipedia)

- Alcohol (Erowid Vault)

- Ethanol (DrugBank)

- Ethanol (Drugs-Forum)

References

- ↑ Risks of Combining Depressants - TripSit

- ↑ "Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–111". Archived from the original on 2025-07-13 – via monographs.iarc.who.int.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health". World Health Organization. 4 January 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Collins SE, Kirouac M (2013). "Alcohol Consumption". Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. pp. 61–65. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_626. ISBN 978-1-4419-1004-2. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "CollinsKirouac2013" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Arnold, John P. (2005). Origin and History of Beer and Brewing: From Prehistoric Times to the Beginning of Brewing Science and Technology (Reprint ed.). Cleveland, OH: BeerBooks. ISBN 0-9662084-1-2.

- ↑ Elizabeth Fernandez (February 27, 2017). Timothy E. Corden, ed. "Pediatric Ethanol Toxicity". Medscape. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Minimum Age Limits Worldwide". ICAP. January 2010. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Drinking Levels and Patterns Defined | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)". www.niaaa.nih.gov.

- ↑ Szmigin, I.; Griffin, C.; Mistral, W.; Bengry-Howell, A.; Weale, L.; Hackley, C. (October 2008). "Re-framing 'binge drinking' as calculated hedonism: Empirical evidence from the UK". The International journal on drug policy. 19 (5): 359–66. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.08.009. eISSN 1873-4758. ISSN 0955-3959. PMID 17981452.

- ↑ Guise, J. M.; Gill, J. S. (December 2007). "'Binge drinking? It's good, it's harmless fun': a discourse analysis of accounts of female undergraduate drinking in Scotland". Health education research. 22 (6): 895–906. doi:10.1093/her/cym034. eISSN 1465-3648. ISSN 0268-1153. OCLC 12824066. PMID 17675648.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Szalavitz, Maia (May 14, 2012). "DSM-5 Could Categorize 40% of College Students as Alcoholics". Time.com. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ↑ Sanderson, Megan (May 21, 2012). "About 37 percent of college students could now be considered alcoholics". Daily Emerald. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Alcohol Facts and Statistics". National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). March 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ↑ Oscar Quine (January 14, 2016). "Generation Abstemious: More and more young people are shunning alcohol". The Independent. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ↑ Crum, R. M.; La Flair, L.; Storr, C. L.; Green, K. M.; Stuart, E. A.; Alvanzo, A. A.; Lazareck, S.; Bolton, J. M.; Robinson, J.; Sareen, J.; Mojtabai, R. (2013). "Reports of Drinking to Self-medicate Anxiety Symptoms: Longitudinal Assessment for Subgroups of Individuals with Alcohol Dependence". Depression and Anxiety. 30 (2): 174–183. doi:10.1002/da.22024. eISSN 1520-6394. ISSN 1091-4269. OCLC 858833641. PMC 4154590

. PMID 23280888.

. PMID 23280888.

- ↑ Soileau M (August 2012). "Spreading the Sofra: Sharing and Partaking in the Bektashi Ritual Meal"

. History of Religions. 52 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1086/665961. JSTOR 10.1086/665961. Retrieved June 5, 2021.

. History of Religions. 52 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1086/665961. JSTOR 10.1086/665961. Retrieved June 5, 2021.

- ↑ Bocking B (1997). A popular dictionary of Shintō (Rev. ed.). Richmond, Surrey [U.K.]: Curzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-1051-5. OCLC 264474222.

- ↑ McGovern, Patrick E.; Zhang, Juzhong; Tang, Jigen; Zhang, Zhiqing; Hall, Gretchen R.; Moreau, Robert A.; Nuñez,, Alberto; Butrym, Eric D.; Richards, Michael P.; Wang, Chen-shan; Cheng, Guangsheng; Zhao, Zhijun; Wang, Changsui (21 December 2004). "Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (51): 17593–17598. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407921102. eISSN 1091-6490. ISSN 0027-8424. OCLC 43473694. PMC 539767

. PMID 15590771.

. PMID 15590771.

- ↑ Rosso, A. M. (2012). "Beer and wine in antiquity: beneficial remedy or punishment imposed by the Gods?". Acta Med Hist Adriat. 10 (2): 237–62. eISSN 1334-6253. ISSN 1334-4366. OCLC 56792775. PMID 23560753.

- ↑ Ruthven M (1997). Islam: a very short introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-154011-0. OCLC 43476241.

- ↑ Gentry K (2001). God Gave Wine. Oakdown. pp. 3ff. ISBN 0-9700326-6-8.

- ↑ "7b". Megillah (Talmud).

Rava said: A person is obligated to become intoxicated with wine on Purim until he is so intoxicated that he does not know how to distinguish between cursed is Haman and blessed is Mordecai.

- ↑ Borras L, Khazaal Y, Khan R, Mohr S, Kaufmann YA, Zullino D, Huguelet P (December 2010). "The relationship between addiction and religion and its possible implication for care". Substance Use & Misuse. 45 (14): 2357–2410. doi:10.3109/10826081003747611. PMC 4137975

. PMID 21039108.

. PMID 21039108.

- ↑ "Drinking on Purim". aishcom (in English). 28 February 2015.

- ↑ Popova S, Dozet D, Shield K, Rehm J, Burd L (September 2021). "Alcohol's Impact on the Fetus". Nutrients. 13 (10): 3452. doi:10.3390/nu13103452

. PMC 8541151

. PMC 8541151  Check

Check |pmc=value (help). PMID 34684453. - ↑ Chung DD, Pinson MR, Bhenderu LS, Lai MS, Patel RA, Miranda RC (August 2021). "Toxic and Teratogenic Effects of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure on Fetal Development, Adolescence, and Adulthood". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (16): 8785. doi:10.3390/ijms22168785

. PMC 8395909

. PMC 8395909  Check

Check |pmc=value (help). PMID 34445488. - ↑ "More than 3 million US women at risk for alcohol-exposed pregnancy". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2 February 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

'drinking any alcohol at any stage of pregnancy can cause a range of disabilities for their child,' said Coleen Boyle, Ph.D., director of CDC's National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Lalli Nykänen; Heikki Suomalainen (1983). Aroma of Beer, Wine and Distilled Alcoholic Beverages. Springer. ISBN 90-277-1553-X.

- ↑ Nelson, Max (2005). The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 0-415-31121-7. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- ↑ "2-Methyl-2-Butanol Reports". Erowid. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ↑ Lachenmeier, D. W.; Haupt, S.; Schulz, K. (2007). "Defining maximum levels of higher alcohols in alcoholic beverages and surrogate alcohol products". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 50 (3): 313–321. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.12.008. ISSN 0273-2300. OCLC 485750423. PMID 18295386.

- ↑ Schaffarzick, Ralph W.; Brown, Beverly J. (1952). "The Anticonvulsant Activity and Toxicity of Methylparafynol (Dormison®) and Some Other Alcohols". Science. 116 (3024): 663–665. doi:10.1126/science.116.3024.663. eISSN 1095-9203. ISSN 0036-8075. OCLC 1644869. PMID 13028241.

- ↑ Hans Brandenberger; Robert A. A. Maes, eds. (1997). Analytical Toxicology for Clinical, Forensic and Pharmaceutical Chemists. Berlin, DE: Walter de Gruyter. p. 401. ISBN 3-11-010731-7.

- ↑ Yandell, D. W.; Cottell, H. A.; Smith, D. T. (1888). "Amylene hydrate, a new hypnotic". The American Practitioner and News. Lousville KY: John P. Morton & Co. 5: 88–89.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Carey, Francis (2000). "Chapter 15: Alcohols, Diols and Thiols". Organic Chemistry (4th ed.). ISBN 0072905018. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ↑ John L. Ingraham (May 2010). "Understanding Congeners in Wine: How does fusel oil form, and how important is it?". Wines & Vines. Wine Communications Group. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 Richard B. Philp (September 15, 2015). Ecosystems and Human Health: Toxicology and Environmental Hazards (Third ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. 216 ff. ISBN 978-1-4987-6008-9.

- ↑ "n-Butyl Alcohol" (PDF). UN Environment Knowledge Repository. September 14, 2001. CAS N°: 71-36-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 2, 2006. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ McCreery, M. J.; Hunt, W. A. (1978). "Physico-chemical correlates of alcohol intoxication". Neuropharmacology. 17 (7): 451–61. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(78)90050-3. eISSN 1873-7064. ISSN 0028-3908. OCLC 01796748. PMID 567755.

- ↑ "Chapter 2: Alcohol and the Brain: Neuroscience and Neurobehavior - The Neurotoxicity of Alcohol" (PDF). 10th Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health: Highlights from Current Research. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. June 2000. p. 134. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

The brain is a major target for the actions of alcohol, and heavy alcohol consumption has long been associated with brain damage. Studies clearly indicate that alcohol is neurotoxic, with direct effects on nerve cells. Chronic alcohol abusers are at additional risk for brain injury from related causes, such as poor nutrition, liver disease, and head trauma.

- ↑ Brust, John C. M. (2010). "Ethanol and Cognition: Indirect Effects, Neurotoxicity and Neuroprotection: A Review". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 7 (4): 1540–1557. doi:10.3390/ijerph7041540. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 2872345

. PMID 20617045.

. PMID 20617045.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Lawrence, A. J.; Beart, P. M.; Kalivas, P. W. (2008). "Neuropharmacology of addiction—setting the scene". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (2). doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.131. eISSN 1476-5381. ISSN 0007-1188. OCLC 01240522. PMC 2442453

. PMID 18414384.

. PMID 18414384.

- ↑ Mihic, S. J.; Ye, Q.; Wick, M. J.; Koltchine, V. V.; Krasowski, M. D.; Finn, S. E.; Mascia, M. P.; Valenzuela, C. F.; Hanson, K. K.; Greenblatt, E. P.; Harris, R. A.; Harrison, N. L. (September 25, 1997). "Sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABAA and glycine receptors". Nature. 389 (6649): 385–389. doi:10.1038/38738. eISSN 1476-4687. ISSN 0028-0836. OCLC 01586310. PMID 9311780.

- ↑ Lovinger, David M. (1999). "5-HT3 receptors and the neural actions of alcohols: an increasingly exciting topic". Neurochemistry International. 35 (2): 125–130. doi:10.1016/S0197-0186(99)00054-6. eISSN 1872-9754. ISSN 0197-0186. OCLC 05937082.

- ↑ Narahashi, Toshio; Aistrup, Gary L.; Marszalec, William; Nagata, Keiichi (1999). "Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: a new target site of ethanol". Neurochemistry International. 35 (2): 131–141. doi:10.1016/S0197-0186(99)00055-8. eISSN 1872-9754. ISSN 0197-0186. OCLC 05937082. PMID 10405997.

- ↑ Allen-Gipson, D. S.; Jarrell, J. C.; Bailey, K. L.; Robinson, J. E.; Kharbanda, K. K.; Sisson, J. H.; Wyatt, T. A. (2009). "Ethanol Blocks Adenosine Uptake via Inhibiting the Nucleoside Transport System in Bronchial Epithelial Cells". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 33 (5): 791–798. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00897.x. eISSN 1530-0277. ISSN 0145-6008. OCLC 02777940. PMC 2940831

. PMID 19298329.

. PMID 19298329.

- ↑ Hoffman PL, Rabe CS, Grant KA, Valverius P, Hudspith M, Tabakoff B. Ethanol and the NMDA receptor. Alcohol. 1990 May-Jun;7(3):229-31. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(90)90010-a. PMID: 2158789.

- ↑ Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Lemos, J. R.; Treistman, S. N. (1994). "Ethanol directly modulates gating of a dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ channel in neurohypophysial terminals". The Journal of Neuroscience. 14 (9): 5453–5460. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05453.1994. eISSN 1529-2401. ISSN 0270-6474. OCLC 476317794. PMID 7521910. PMC 6577079.

- ↑ Mitchell MC, Jr; Teigen, EL; Ramchandani, VA (May 2014). "Absorption and peak blood alcohol concentration after drinking beer, wine, or spirits". Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 38 (5): 1200–4. doi:10.1111/acer.12355. PMC 4112772

. PMID 24655007.

. PMID 24655007.

- ↑ "Champagne does get you drunk faster". New Scientist.

- ↑ "Regulation (EC) No 110/2008 Of The European Parliament And Of The Council". Official Journal of the European Union. EUR-Lex. February 13, 2008. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ Inge Russell, ed. (2003). Whisky: Technology, Production and Marketing. Alcoholic Beverages Series. Graham Stewart; Charles Bamforth, series ed. London, UK: Academic Press. p. 180. ISBN 0-12-669202-5.

- ↑ Heaton MB, Mitchell JJ, Paiva M (April 2000). "Amelioration of ethanol-induced neurotoxicity in the neonatal rat central nervous system by antioxidant therapy". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 24 (4): 512–18. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02019.x. PMID 10798588.

- ↑ Brust JC (April 2010). "Ethanol and cognition: indirect effects, neurotoxicity and neuroprotection: a review". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 7 (4): 1540–57. doi:10.3390/ijerph7041540

. PMC 2872345

. PMC 2872345  . PMID 20617045.

. PMID 20617045.

- ↑ Witt, K.; Jochum, T.; Bär, K. J.; Voss, A. (2010). "Application of an Electronic Nose to Diagnose Liver Cirrhosis from the Skin Surface". In Dössel; Schlegel. World Congress on Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, September 7 - 12, 2009, Munich, Germany. IFMBE Proceedings. 25/8. Springer. pp. 150–152. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-03887-7_41. ISBN 978-3-642-03886-0.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 British National Formulary: BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 42, 838. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ↑ Pohorecky, L. A.; Brick, J. (1988). "Pharmacology of ethanol". Pharmacol. Ther. 36 (2-3): 335–427. doi:10.1016/0163-7258(88)90109-x. eISSN 1879-016X. ISSN 0163-7258. PMID 3279433.

- ↑ Becker, Daniel E. (2007). "Drug Therapy in Dental Practice: General Principles: Part 2—Pharmacodynamic Considerations". Anesth Prog. 54 (1): 19–24. doi:10.2344/0003-3006(2007)54[19:DTIDPG]2.0.CO;2. eISSN 1878-7177. ISSN 0003-3006. PMC 1821133

. PMID 17352523.

. PMID 17352523.

- ↑ WHO Model Formulary 2008 (PDF). World Health Organization. 2009. p. 321. ISBN 9789241547659. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ↑ Barceloux D. G.; Bond G. R.; Krenzelok E. P.; Cooper H.; Vale J. A. (2002). "American Academy of Clinical Toxicology practice guidelines on the treatment of methanol poisoning". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 40 (4): 415–46. doi:10.1081/CLT-120006745. eISSN 1097-9875. ISSN 0731-3810. PMID 12216995.

- ↑ Nutt, David; King, Leslie A.; Saulsbury, William; Blakemore, Colin (2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. eISSN 1474-547X. ISSN 0140-6736. OCLC 01755507. PMID 17382831.

- ↑ Ronksley, P. E.; Brien, S. E.; Turner, B. J.; Mukamal, K. J.; Ghali, W. A. (2011). "Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The BMJ. 342:d671. doi:10.1136/bmj.d671. eISSN 1756-1833. ISSN 0959-8138. OCLC 3259564. PMC 3043109

. PMID 21343207.

. PMID 21343207.

- ↑ Tolstrup, Janne; Jensen, Majken K.; Anne, Tjønneland; Overvad, Kim; Mukamal, Kenneth J.; Grønbæk, Morten (2006). "Prospective study of alcohol drinking patterns and coronary heart disease in women and men". The BMJ. 332 (7552): 1244–1248. doi:10.1136/bmj.38831.503113.7C. eISSN 1756-1833. ISSN 0959-8138. OCLC 3259564. PMC 1471902

. PMID 16672312.

. PMID 16672312.

- ↑ "Health Risks and Benefits of Alcohol Consumption" (PDF). Alcohol Research & Health. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 24 (1): 5–11. 2000. ISSN 1535-7414. OCLC 42453373. PMC 671300

. PMID 11199274.

. PMID 11199274.

- ↑ Müller, D.; Koch, R. D.; von Specht, H.; Völker, W.; Münch, E. M. (1985). "Neurophysiologic findings in chronic alcohol abuse". Psychiatr. Neurol. Med. Psychol. (Leipz). 37 (3): 129–132. ISSN 0033-2739. OCLC 01643487. PMID 2988001.

- ↑ Testino, G. (2008). "Alcoholic diseases in hepato-gastroenterology: a point of view". Hepatogastroenterology. 55 (82-83): 371–377. ISSN 0172-6390. OCLC 645110783. PMID 18613369.

- ↑ Woody Caan; Jackie de Belleroche (2002). Drink, Drugs and Dependence: From Science to Clinical Practice. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415278911.

- ↑ Guerri, Consuelo; Pascual, María (2010). "Mechanisms involved in the neurotoxic, cognitive, and neurobehavioral effects of alcohol consumption during adolescence". Alcohol. 44 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.10.003. eISSN 1873-6823. ISSN 0741-8329. PMID 20113871.

- ↑ Cogliano, V. J.; Baan, R.; Straif, K.; Grosse, Y.; Lauby-Secretan, B.; El Ghissassi, F.; Bouvard, V.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Guha, N.; Freeman, C.; Galichet, L.; Wild, C. P. (December 21, 2011). "Preventable Exposures Associated With Human Cancers". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 103 (24): 1827–39. doi:10.1093/jnci/djr483. eISSN 1460-2105. ISSN 0027-8874. OCLC 01064763. PMC 3243677

. PMID 22158127.

. PMID 22158127.

- ↑ Roberts, C.; Robinson, S.P. (2007). "Alcohol concentration and carbonation of drinks: The effect on blood alcohol levels". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 14 (7): 398–405. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2006.12.010. eISSN 1878-7487. ISSN 1752-928X. OCLC 612913525. PMID 17720590.

- ↑ https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/04-01-2023-no-level-of-alcohol-consumption-is-safe-for-our-health. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Arora, Monika; ElSayed, Ahmed; Beger, Birgit; Naidoo, Pamela; Shilton, Trevor; Jain, Neha; Armstrong-Walenczak, Kelcey; Mwangi, Jeremiah; Wang, Yunshu; Eiselé, Jean-Luc; Pinto, Fausto J.; Champagne, Beatriz M. (2022-07-22). "The Impact of Alcohol Consumption on Cardiovascular Health: Myths and Measures". Global Heart. 17 (1): 45. doi:10.5334/gh.1132

. ISSN 2211-8179. PMC 9306675

. ISSN 2211-8179. PMC 9306675  Check

Check |pmc=value (help). PMID 36051324. - ↑ Salamon, Maureen (1 May 2022). "Want a healthier heart? Seriously consider skipping the drinks". Harvard Health (in English). Archived from the original on 31 May 2024. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ↑ "Less meat, more plant-based: Here are the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023". www.norden.org. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ↑ Hall, J. A.; Moore, C. B. (2008). "Drug facilitated sexual assault – A review". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 15 (5): 291–7. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2007.12.005. eISSN 1878-7487. ISSN 1752-928X. OCLC 612913525. PMID 18511003.

- ↑ Beynon, C. M.; McVeigh, C.; McVeigh, J.; Leavey, C.; Bellis, M. A. (2008). "The Involvement of Drugs and Alcohol in Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault: A Systematic Review of the Evidence". Trauma Violence Abuse. 9 (3): 178–88. doi:10.1177/1524838008320221. PMID 18541699.

- ↑ Schwartz, R. H.; Milteer, R.; LeBeau, M. A. (2000). "Drug-facilitated sexual assault ('date rape')". South. Med. J. 93 (6): 558–61. eISSN 1541-8243. ISSN 0038-4348. OCLC 01766196. PMID 10881768.

- ↑ Penning R, van Nuland M, Fliervoet LA, Olivier B, Verster JC (June 2010). "The pathology of alcohol hangover". Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 3 (2): 68–75. doi:10.2174/1874473711003020068. PMID 20712596.

- ↑ Wiese JG, Shlipak MG, Browner WS (June 2000). "The alcohol hangover". Annals of Internal Medicine. 132 (11): 897–902. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-132-11-200006060-00008. PMID 10836917.

- ↑ Breene, Sophia (October 6, 2016). "The best and worst foods to cure a hangover". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ↑ "A Few Too Many: Is there any hope for the hung over?". The New Yorker. May 26, 2008.

- ↑ Harding, Anne (December 21, 2010). "10 Hangover Remedies: What Works?". Health.com. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ↑ Howard, Jacqueline (March 17, 2017). "What to eat to beat a hangover". CNN. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Yost, David A. (December 2002). "Acute care for alcohol intoxication: Be prepared to consider clinical dilemmas" (PDF). Postgraduate Medicine. 112 (6): 14–16, 21–22, 25–26. eISSN 1941-9260. ISSN 0032-5481. OCLC 643598155. PMID 12510444. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 14, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ Denise Mann (September 6, 2012). "Non-Alcoholic Red Wine May Boost Heart Health". WebMD. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ↑ Knott, Craig S.; Coombs, Ngaire; Stamatakis, Emmanuel (2015). "All cause mortality and the case for age specific alcohol consumption guidelines: pooled analyses of up to 10 population based cohorts". The BMJ. 350:h384. doi:10.1136/bmj.h384. eISSN 1756-1833. ISSN 0959-8138. OCLC 3259564. PMC 4353285

. PMID 25670624.

. PMID 25670624.