MDEA

| Summary sheet: MDEA |

| MDEA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Nomenclature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common names | MDEA, MDE, Eve | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Substitutive name | 3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-ethylamphetamine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systematic name | (RS)-1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-N-ethylpropan-2-amine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Class Membership | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Psychoactive class | Entactogen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chemical class | Amphetamine / MDxx | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Routes of Administration | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interactions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MXE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dissociatives | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DXM | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MDMA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stimulants | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25x-NBOMe | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25x-NBOH | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tramadol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MAOIs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SNRIs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stimulants | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cocaine | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serotonin releasers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SSRIs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5-HTP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-ethylamphetamine (also known as MDEA, MDE, and colloquially as Eve) is a lesser-known entactogen substance of the amphetamine class. MDEA is chemically similar to MDMA and MDA.[1] It produces its effects by increasing levels of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine in the brain.[2]

The first recorded human use of MDEA was in 1976 by Alexander Shulgin, who noted its similarity to MDMA in both effects and potency, though faster to act and shorter in duration.[3] The synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of MDEA and a series of related compounds were published in 1980.[4] MDEA is included in Shulgin's 1991 book "PiHKAL" ("Phenethylamines I Have Known and Loved").[1]

In the United States, MDEA was introduced recreationally in 1985 as a legal substitute to the newly banned MDMA before it was made a Schedule I substance two years later.[5] Since then, MDEA has rarely been sold on its own and has largely been used as an occasional additive or substitute ingredient in pills of "Ecstasy".[2]

Very little data exists about the pharmacological properties, metabolism, and toxicity of MDEA,. As a result it is highly advised to approach this potentially habit-forming entactogenic substance with the proper amount of precaution and harm reduction practices if choosing to use it.

History and culture

This History and culture section is a stub. As a result, it may contain incomplete or wrong information. You can help by expanding it. |

In the United States, MDEA was introduced recreationally in 1985 as a legal substitute to the newly banned MDMA before it was made a Schedule I substance two years later on August 13, 1987 under the Federal Analogue Act.[5] Since then, MDEA has rarely been sold on its own and has largely been used as an occasional additive or substitute ingredient in pills of "Ecstasy" (for instance, studies conducted in the 1990s found MDEA present in approximately four percent of ecstasy tablets).[2]

While MDEA shares many of the core entactogenic properties of MDMA, it is slightly less potent and considered to be more "stoning", lacking the pro-socializing and energizing "magic" most party-goers seek in their MDMA experiences. As a result, it is largely considered by most people to be a less desirable variant of MDMA and is thus rarely produced and sold in the illicit drug market, typically showing up only in small batches synthesized and distributed by hobbyist clandestine chemists.[citation needed]

Chemistry

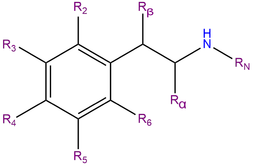

MDEA, also known as 3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-ethylamphetamine, is a synthetic molecule of the substituted amphetamine chemical class. Molecules of the amphetamine class contain a phenethylamine core featuring a phenyl ring bound to an amino (NH2) group through an ethyl chain with an additional methyl substitution at Rα. Additionally, MDEA contains an ethyl substitution on RN, which is a single carbon extension of the methyl group present in MDMA. MDEA also contains substitutions at R3 and R4 of the phenyl ring with oxygen groups that are incorporated into a methylenedioxy ring through a methylene bridge. MDEA shares this methylenedioxy ring with other entactogens like MDMA, MDA and MDAI.

Pharmacology

MDEA acts as a releasing agent and reuptake inhibitor of the monoamine neurotransmitters serotonin, dopamine and noradrenaline[2]. These neurotransmitters are responsible for modulating focus, motivation, pleasure, and reward.

The "stoning" effects of MDEA are thought to arise from the higher relative activity MDEA has on releasing serotonin over dopamine compared to MDMA.

MDEA stimulates the release of oxytocin and prolactin, two hormones that are currently being studied for their potential roles in modulating the feeling of trust and love.[6]

Subjective effects

|

This subjective effects section is a stub. As such, it is still in progress and may contain incomplete or wrong information. You can help by expanding or correcting it. |

Disclaimer: The effects listed below cite the Subjective Effect Index (SEI), an open research literature based on anecdotal user reports and the personal analyses of PsychonautWiki contributors. As a result, they should be viewed with a healthy degree of skepticism.

It is also worth noting that these effects will not necessarily occur in a predictable or reliable manner, although higher doses are more liable to induce the full spectrum of effects. Likewise, adverse effects become increasingly likely with higher doses and may include addiction, severe injury, or death ☠.

Physical effects

-

- Stimulation & Sedation - In terms of its effects on the user's physical energy levels, MDEA is commonly regarded as significantly less stimulating and energizing than MDMA, while still retaining its core entactogenic effects. Unlike MDMA, which encourages activities such as running, climbing and dancing in a way that makes it a popular choice for musical events such as festivals and raves. The distinct style of stimulation which MDEA presents can be described as mildly to moderately forced, trending more towards sedation and relaxation. This means that at higher doses, it becomes difficult or impossible to keep still as jaw clenching, involuntarily body shakes and vibrations become present, resulting in an extreme unsteadiness of the hands and a general lack of motor control, though to a far lesser degree than with MDMA.

- Spontaneous bodily sensations - The "body high" of MDEA can be characterized as a moderate to extreme euphoric relaxing sensation that encompasses the entire body. It is capable of becoming overwhelmingly pleasurable at higher doses to the point of "flooring" or immobilizing the user. This sensation maintains a consistent presence that steadily rises with the onset and hits its limit once the peak has been reached, before steadily dropping off.

- Physical euphoria

- Perception of bodily heaviness - This effect, combined with sedation, is possibly the basis for why MDEA is frequently characterized as "stoning" relative to other entactogens, which often have more pronounced stimulating effects.

- Tactile enhancement

- Vibrating vision - At high doses, a person's eyeballs may begin to spontaneously wiggle back and forth in a rapid motion, causing the vision to become blurry and temporarily out of focus. This is a condition known as nystagmus.

- Temperature regulation suppression - As MDEA is a serotonin releasing agent, rise in core body temperature tends to be high and consistent throughout the experience. Caution must be taken as too high of a dose results in serotonin syndrome which can be fatal if left untreated.

- Increased bodily temperature - As MDEA is a serotonin releasing agent, rise in core body temperature tends to be high and consistent throughout the experience. Caution must be taken as too high of a dose results in serotonin syndrome which can be fatal if left untreated.

- Dehydration - Like related entactogenic stimulants, feelings of dry mouth and dehydration are a universal experience with MDEA; this effect is a product of an increased heart rate and metabolism. While it is important to avoid becoming dehydrated (especially when out dancing in a hot environment) there have been a number of users who have suffered from water intoxication through over-drinking, so it is advised that users simply sip at the water and never over-drink.

- Difficulty urinating - Higher doses of MDEA result in an overall difficulty when it comes to urination. This is an effect that is completely temporary and harmless. It is caused by MDEA’s promotion of the release of anti-diuretic hormone (ADH); ADH is responsible for regulating urination. This effect can be lessened by simply relaxing, but can be significantly relieved by placing a hot flannel over the genitals to warm them up and encourage blood flow.

- Increased blood pressure

- Increased heart rate

- Increased perspiration

- Bodily control enhancement

- Appetite suppression

- Brain zaps

- Pupil dilation

- Stamina enhancement

- Teeth grinding - This component is usually only present in the higher dose range, and to a lesser extent than the teeth grinding associated with MDMA.

- Temporary erectile dysfunction

Visual effects

-

Enhancements

MDEA presents an array of visual enhancements which are mild in comparison to traditional psychedelics, but still distinctively present. These generally include:

Suppressions

Distortions

Hallucinatory states

MDEA is capable of producing a unique range of low and high-level hallucinatory states in a fashion that is significantly less consistent and reproducible than that of many other commonly used psychedelics. These effects are far more common during the offset of the experience and commonly include:

Cognitive effects

-

The cognitive effects of MDEA can be broken down into several components which progressively intensify proportional to dosage. The broad head space of MDEA is described by many as one of moderate mental stimulation, feelings of love, warmth or empathy and powerful relaxing euphoria. It contains a large number of typical psychedelic, entactogenic and stimulating cognitive effects.

The most prominent of these cognitive effects generally include:

- Anxiety suppression

- Empathy, affection, and sociability enhancement - This particular effect is present, but not nearly as consistent, pronounced, powerful and therapeutic than one would experience with MDMA With time and repeated use, however, this effect becomes severely diminished as the perspective it instills becomes fully grounded and already in place, making people feel merely stimulated and euphoric with no new found urges to communicate, with others. Some users report that MDEA "loses its magic" with as few as 10 experiences, while others have reported hundreds of uses before the empathic qualities disappear. This does not appear to be valid for all users, however, with many users reporting that they have not experienced any decrease in quality of the experience despite dozens or even hundreds of uses.

- Disinhibition

- Cognitive euphoria - Strong emotional euphoria and feelings of happiness are present within MDEA and are likely a direct result of serotonin and dopamine release.

- Increased music appreciation

- Time distortion - Strong feelings of time compression are common within MDEA and speed up the experience of time quite noticeably.

- Compulsive redosing

- Creativity enhancement

- Focus enhancement - This component is most effective at low to moderate doses of anything higher will usually impair concentration.

- Immersion enhancement

- Motivation enhancement

- Increased libido

- Mindfulness

- Thought acceleration

- Wakefulness

Auditory effects

Transpersonal effects

-

- Existential self-realization

- Unity and interconnectedness - Experiences of unity, oneness and interconnectedness between level 1 - 2 are common within MDEA.[citation needed]

After effects

-

The effects which occur during the offset of a stimulant experience generally feel negative and uncomfortable in comparison to the effects which occurred during its peak. This is often referred to as a "comedown" and occurs because of neurotransmitter depletion. Its effects commonly include:

- Anxiety

- Appetite suppression

- Cognitive fatigue

- Depression

- Dream potentiation & Dream suppression - Some users note extremely strange, vivid and sometimes rather scary dreams for several nights after taking large doses of MDEA.

- Sleep paralysis - Some users note sleep paralysis after consuming MDEA, particularly in high doses or in conjunction with other factors such as lack of sleep or physical fatigue.

- Irritability

- Motivation suppression

- Thought deceleration

- Wakefulness

Experience reports

There are currently no anecdotal reports which describe the effects of this compound within our experience index. Additional experience reports can be found here:

Toxicity and harm potential

Short-term physical health risks of MDEA consumption include dehydration, insomnia, hyperthermia,[7][8] and hyponatremia.[9] Continuous activity without sufficient rest or rehydration may cause body temperature to rise to dangerous levels, and loss of fluid via excessive perspiration puts the body at further risk as the stimulatory and euphoric qualities of the drug may render the user oblivious to their energy expenditure for quite some time. Diuretics such as alcohol may exacerbate these risks further.

The exact toxic dosage is unknown, but considered to be far greater than its active dose.

Neurotoxicity

As with MDMA, the neurotoxicity of MDEA use has long been the subject of debate. Scientific study has resulted in the general agreement that, although it is physically safe to try in a responsible context, the administration of repeated or high dosages of MDEA is likely to be neurotoxic and cardiotoxic in some form.

Like other powerful serotonin releasing agents, MDEA is thought to cause down-regulation of serotonin reuptake transporters in the brain. The rate at which the brain recovers from serotonergic changes is unclear. One study demonstrated lasting serotonergic changes in some animals exposed to MDMA, which likely applies to MDEA as well.[10] Other studies have suggested that the brain may recover from serotonergic damage.[11][12][13]

Cardiotoxicity

Like with MDMA, the long-term heavy use of MDEA is likely similarly cardiotoxic, leading to valvulopathy through its actions on the 5-HT2B receptor.[14] In one study, 28% of long-term MDMA users (2-3 doses per week for a mean of 6 years, mean of age 24.3 years) had developed clinically evident valvular heart disease.[15]

It is strongly recommended that one use harm reduction practices when using this substance.

Tolerance and addiction potential

As with other stimulants, the chronic use of MDEA can be considered moderately addictive with a high potential for abuse and is capable of causing psychological dependence among certain users. When addiction has developed, cravings and withdrawal effects may occur if a person suddenly stops their usage.

Tolerance to many of the effects of MDEA develops with prolonged and repeated use. This results in users having to administer increasingly larger doses to achieve the same effects. After that, it takes about 1-1.5 months for the tolerance to be reduced to half and 2-3 months to be back at baseline (in the absence of further consumption). MDEA presents cross-tolerance with all dopaminergic and serotonergic stimulants and entactogens, meaning that after the consumption of MDEA all of these will have a reduced effect.

Dangerous interactions

Warning: Many psychoactive substances that are reasonably safe to use on their own can suddenly become dangerous and even life-threatening when combined with certain other substances. The following list provides some known dangerous interactions (although it is not guaranteed to include all of them).

Always conduct independent research (e.g. Google, DuckDuckGo, PubMed) to ensure that a combination of two or more substances is safe to consume. Some of the listed interactions have been sourced from TripSit.

- 25x-NBOMe & 25x-NBOH - 25x compounds are highly stimulating and physically straining. Combinations with MDEA should be strictly avoided due to the risk of excessive stimulation and heart strain. This can result in increased blood pressure, vasoconstriction, panic attacks, thought loops, seizures, and heart failure in extreme cases.

- Alcohol - Combining alcohol with stimulants can be dangerous due to the risk of accidental over-intoxication. Stimulants mask alcohol's depressant effects, which is what most people use to assess their degree of intoxication. Once the stimulant wears off, the depressant effects will be left unopposed, which can result in blackouts and severe respiratory depression. If mixing, the user should strictly limit themselves to only drinking a certain amount of alcohol per hour.

- DXM - Combinations with DXM should be avoided due to its inhibiting effects on serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. There is an increased risk of panic attacks and hypertensive crisis, or serotonin syndrome with serotonin releasers (MDMA, methylone, mephedrone, etc.). Monitor blood pressure carefully and avoid strenuous physical activity.

- MDMA - Any neurotoxic effects of MDMA are likely to be increased when other stimulants are present. There is also a risk of excessive blood pressure and heart strain (cardiotoxicity).

- MXE - Some reports suggest combinations with MXE may dangerously increase blood pressure and increase the risk of mania and psychosis.

- Dissociatives - Both classes carry a risk of delusions, mania and psychosis, and these risk may be multiplied when combined.

- Stimulants - MDEA may be dangerous to combine with other stimulants like cocaine as they can increase one's heart rate and blood pressure to dangerous levels.

- Tramadol - Tramadol is known to lower the seizure threshold[16] and combinations with stimulants may further increase this risk.

- MAOIs - This combination may increase the amount of neurotransmitters such as dopamine to dangerous or even fatal levels. Examples include syrian rue, banisteriopsis caapi, and some antidepressants.[17]

- Stimulants - The neurotoxic effects of MDEA may be increased when combined with other stimulants.

- Cocaine - This combination may increase strain on the heart.

Serotonin syndrome risk

Combinations with the following substances can cause dangerously high serotonin levels. Serotonin syndrome requires immediate medical attention and can be fatal if left untreated.

- MAOIs - Such as banisteriopsis caapi, syrian rue, phenelzine, selegiline, and moclobemide.[18]

- Serotonin releasers - Such as MDMA, 4-FA, methamphetamine, methylone and αMT.

- SSRIs - Such as citalopram and sertraline

- SNRIs - Such as tramadol and venlafaxine

- 5-HTP

There is an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when MDEA is taken with many antidepressants, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). Additionally, if MDEA is taken with SSRIs and SNRIs, the MDEA will be significantly less powerful or may have no distinguishable effects at all.

Legal status

|

This legality section is a stub. As such, it may contain incomplete or wrong information. You can help by expanding it. |

Internationally, MDEA is part of the the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 as a Schedule I substance.[19] (MDE)

- Austria: MDEA is illegal to possess, produce and sell under the SMG (Suchtmittelgesetz Österreich).[citation needed]

- Brazil: MDEA is illegal to possess, produce or sell as it is listed on Portaria SVS/MS nº 344 as "MDE".[20]

- Canada: MDEA is listed on the CSDA in Schedule I.[21]

- France: MDEA is scheduled as a "stupéfiant", i.e. a recognized drug of abuse. It is illegal to possess, buy, sell or manufacture.[22]

- Germany: MDEA is controlled under Anlage I BtMG (Narcotics Act, Schedule I) as of April 15, 1991.[23][24] It is illegal to manufacture, possess, import, export, buy, sell, procure or to dispense it without a license.[25] (MDE)

- Switzerland: MDEA is a controlled substance specifically named under Verzeichnis D.[26]

- United Kingdom: MDEA is a Class A drug.[citation needed]

- United States: MDEA is a Schedule I drug.[citation needed]

See also

External links

Literature

- Freudenmann RW, Spitzer M (2004). The Neuropsychopharmacology and Toxicology of 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-ethyl-amphetamine (MDEA). CNS Drug Reviews. 10 (2): 89–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-3458.2004.tb00007.x. PMID 15179441.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Read #22 2C-C | PiHKAL · info". isomerdesign.com.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Freudenmann, R. W., Spitzer, M. (2004). "The Neuropsychopharmacology and Toxicology of 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-ethyl-amphetamine (MDEA)". CNS drug reviews. 10 (2): 89–116. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2004.tb00007.x. ISSN 1080-563X.

- ↑ Shulgin, Alexander. "Pharmacology Lab Notes #2". Lafayette, CA. (1976-1980). p206 (Erowid.org) | https://erowid.org/library/books_online/shulgin_labbooks/shulgin_labbook2_searchable.pdf

- ↑ Braun, U., Shulgin, A. T., Braun, G. (February 1980). "Centrally active N-substituted analogs of 3,4-methylenedioxyphenylisopropylamine (3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine)". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 69 (2): 192–195. doi:10.1002/jps.2600690220. ISSN 0022-3549.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Read #106 MDE - PiHKAL · info

- ↑ Passie, T. (2012). Healing with entactogens: therapist and patient perspectives on MDMA-assisted group psychotherapy. Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). ISBN 9780979862274.

- ↑ Nimmo, S. M., Kennedy, B. W., Tullett, W. M., Blyth, A. S., Dougall, J. R. (October 1993). "Drug-induced hyperthermia". Anaesthesia. 48 (10): 892–895. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb07423.x. ISSN 0003-2409.

- ↑ Malberg, J. E., Seiden, L. S. (1 July 1998). "Small changes in ambient temperature cause large changes in 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-induced serotonin neurotoxicity and core body temperature in the rat". The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 18 (13): 5086–5094. ISSN 0270-6474.

- ↑ Wolff, K., Tsapakis, E. M., Winstock, A. R., Hartley, D., Holt, D., Forsling, M. L., Aitchison, K. J. (May 2006). "Vasopressin and oxytocin secretion in response to the consumption of ecstasy in a clubbing population". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 20 (3): 400–410. doi:10.1177/0269881106061514. ISSN 0269-8811.

- ↑ Fischer, C., Hatzidimitriou, G., Wlos, J., Katz, J., Ricaurte, G. (August 1995). "Reorganization of ascending 5-HT axon projections in animals previously exposed to the recreational drug (+/-)3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "ecstasy")". The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 15 (8): 5476–5485. ISSN 0270-6474.

- ↑ Scheffel, U., Szabo, Z., Mathews, W. B., Finley, P. A., Dannals, R. F., Ravert, H. T., Szabo, K., Yuan, J., Ricaurte, G. A. (June 1998). "In vivo detection of short- and long-term MDMA neurotoxicity--a positron emission tomography study in the living baboon brain". Synapse (New York, N.Y.). 29 (2): 183–192. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199806)29:2<183::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-3. ISSN 0887-4476.

- ↑ Reneman, L., Lavalaye, J., Schmand, B., Wolff, F. A. de, Brink, W. van den, Heeten, G. J. den, Booij, J. (1 October 2001). "Cortical Serotonin Transporter Density and Verbal Memory in Individuals Who Stopped Using 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or "Ecstasy"): Preliminary Findings". Archives of General Psychiatry. 58 (10): 901. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.901. ISSN 0003-990X.

- ↑ Selvaraj, S., Hoshi, R., Bhagwagar, Z., Murthy, N. V., Hinz, R., Cowen, P., Curran, H. V., Grasby, P. (April 2009). "Brain serotonin transporter binding in former users of MDMA ('ecstasy')". The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 194 (4): 355–359. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.050344. ISSN 1472-1465.

- ↑ Elangbam, C. S. (October 2010). "Drug-induced Valvulopathy: An Update". Toxicologic Pathology. 38 (6): 837–848. doi:10.1177/0192623310378027. ISSN 0192-6233.

- ↑ Droogmans, S., Cosyns, B., D’haenen, H., Creeten, E., Weytjens, C., Franken, P. R., Scott, B., Schoors, D., Kemdem, A., Close, L., Vandenbossche, J.-L., Bechet, S., Van Camp, G. (1 November 2007). "Possible association between 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine abuse and valvular heart disease". The American Journal of Cardiology. 100 (9): 1442–1445. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.06.045. ISSN 0002-9149.

- ↑ Talaie, H.; Panahandeh, R.; Fayaznouri, M. R.; Asadi, Z.; Abdollahi, M. (2009). "Dose-independent occurrence of seizure with tramadol". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 5 (2): 63–67. doi:10.1007/BF03161089. eISSN 1937-6995. ISSN 1556-9039. OCLC 163567183.

- ↑ Gillman, P. K. (2005). "Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, opioid analgesics and serotonin toxicity". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 95 (4): 434–441. doi:10.1093/bja/aei210

. eISSN 1471-6771. ISSN 0007-0912. OCLC 01537271. PMID 16051647.

. eISSN 1471-6771. ISSN 0007-0912. OCLC 01537271. PMID 16051647.

- ↑ Gillman, P. K. (2005). "Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, opioid analgesics and serotonin toxicity". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 95 (4): 434–441. doi:10.1093/bja/aei210

. eISSN 1471-6771. ISSN 0007-0912. OCLC 01537271. PMID 16051647.

. eISSN 1471-6771. ISSN 0007-0912. OCLC 01537271. PMID 16051647.

- ↑ "CONVENTION ON PSYCHOTROPIC SUBSTANCES 1971" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ↑ http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/documents/10181/3115436/%281%29RDC_130_2016_.pdf/fc7ea407-3ff5-4fc1-bcfe-2f37504d28b7

- ↑ "Controlled Drugs and Substances Act - SCHEDULE I". Government of Canada. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ↑ Arrêté du 22 février 1990 fixant la liste des substances classées comme stupéfiants

- ↑ "Dritte Verordnung zur Änderung betäubungsmittelrechtlicher Vorschriften" (in German). Bundesanzeiger Verlag. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ↑ "Anlage I BtMG" (in German). Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ↑ "§ 29 BtMG" (in German). Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ↑ "Verordnung des EDI über die Verzeichnisse der Betäubungsmittel, psychotropen Stoffe, Vorläuferstoffe und Hilfschemikalien" (in German). Bundeskanzlei [Federal Chancellery of Switzerland]. Retrieved January 1, 2020.