Benzodiazepines

Fatal overdose may occur when benzodiazepines are combined with other depressants such as opiates, barbiturates, gabapentinoids, thienodiazepines, alcohol or other GABAergic substances.[1]

It is strongly discouraged to combine these substances, particularly in common to heavy doses.

Benzodiazepines (commonly referred to as benzos) are a class of psychoactive substances that act as central nervous system depressants. These substances work by magnifying the efficiency and effects of the principal inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by binding to and acting on its receptors.[2]

The characteristic effects of benzodiazepines include anxiety suppression, sedation, muscle relaxation, disinhibition, sleepiness and amnesia. In a medical context, short-acting benzodiazepines are typically recommended for treating insomnia or acute panic attacks while long-acting ones are recommended for the treatment of anxiety disorders.[3]

Sudden discontinuation of benzodiazepines can cause seizures (which may be life-threatening in certain cases[4]) for individuals who have been heavily using them for a prolonged period of time. For this reason, it is recommended to gradually lower the daily dose over a period of time instead of stopping abruptly — a technique known as tapering.[5]

History

The first benzodiazepine, chlordiazepoxide (Librium), was synthesized in 1955 by Leo Sternbach while working at Hoffmann–La Roche on the development of tranquilizers. The pharmacological properties of the compounds prepared initially were disappointing, and Sternbach abandoned the project.

Two years later, on April 1957, co-worker Earl Reeder noticed a "nicely crystalline" compound leftover from the discontinued project while spring-cleaning in the lab. This compound, later named chlordiazepoxide, had not been tested in 1955 because of Sternbach's focus on other issues. Expecting pharmacology results to be negative, and hoping to publish the chemistry-related findings, researchers submitted it for a standard battery of animal tests.

However, the compound showed very strong sedative, anticonvulsant, and muscle relaxant effects. These impressive clinical findings led to its speedy introduction throughout the world in 1960 under the brand name Librium.[6][7] Following chlordiazepoxide, diazepam marketed by Hoffmann–La Roche under the brand name Valium in 1963, and for a while the two were the most commercially successful drugs. The introduction of benzodiazepines led to a decrease in the prescription of barbiturates, and by the 1970s they had largely replaced the older drugs for sedative and hypnotic uses.[8]

Society and culture

The new group of drugs was initially greeted with optimism by the medical profession, but gradually concerns arose; in particular, the risk of dependence became evident in the 1980s. Benzodiazepines have a unique history in that they were responsible for the largest-ever class-action lawsuit against drug manufacturers in the United Kingdom, involving 14,000 patients and 1,800 law firms that alleged the manufacturers knew of the dependence potential but intentionally withheld this information from doctors.

At the same time, 117 general practitioners and 50 health authorities were sued by patients to recover damages for the harmful effects of dependence and withdrawal. This led some doctors to require a signed consent form from their patients and to recommend that all patients be adequately warned of the risks of dependence and withdrawal before starting treatment with benzodiazepines.[9] The court case against the drug manufacturers never reached a verdict; legal aid had been withdrawn and there were allegations that the consultant psychiatrists, the expert witnesses, had a conflict of interest. This litigation led to changes in British law, making class action lawsuits more difficult.[10]

Although antidepressants with anxiolytic properties have been introduced, and there is increasing awareness of the adverse effects of benzodiazepines, prescriptions for short-term anxiety relief have not significantly dropped.[11] For treatment of insomnia, benzodiazepines are now less popular than nonbenzodiazepines, which include zolpidem, zaleplon and eszopiclone.[12] Nonbenzodiazepines are molecularly distinct, but nonetheless, they work on the same benzodiazepine receptors and produce similar sedative effects.[13]

Chemistry

Benzodiazepines are heterocyclic compounds comprised of a benzene ring fused to a seven-member nitrogenous diazepine ring. Benzodiazepine drugs contain an additional substituted phenyl ring bonded at R5, resulting in 5-phenyl-1,4-benzodiazepines with different side groups attached to the structure to create a number of drugs with different strength, duration, and efficacy.

Benzodiazepine drugs commonly contain an aromatic electrophilic substitution such as aromatic halogenation or nitration on R7 of their rings. Benzodiazepines can be subdivided into triazolobenzodiazepines and ketone substituted benzodiazepines. Triazolobenzodiazepines contain a triazole ring bonded to the benzodiazepine structure and are distinguished by the suffix "-zolam." Ketone substituted rings contain a ketone oxygen bond at R2 of their benzodiazepine structure and are distinguished by their suffix "-azepam."

Pharmacology

Benzodiazepines produce a variety of effects by binding to the benzodiazepine receptor site and magnifying the efficiency and effects of the neurotransmitter gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) by acting on its receptors.[2] As this site is the most prolific inhibitory receptor set within the brain, its modulation results in the sedating (or calming effects) of benzodiazepines on the nervous system.

The anticonvulsant properties of benzodiazepines may be, in part or entirely, due to binding to voltage-dependent sodium channels rather than benzodiazepine receptors.[14]

Benzodiazepines function as weak adenosine reuptake inhibitors. It has been suggested that some of their anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, and muscle relaxant effects may be in part mediated by this action.[15]

Subjective effects

Disclaimer: The effects listed below cite the Subjective Effect Index (SEI), an open research literature based on anecdotal user reports and the personal analyses of PsychonautWiki contributors. As a result, they should be viewed with a healthy degree of skepticism.

It is also worth noting that these effects will not necessarily occur in a predictable or reliable manner, although higher doses are more liable to induce the full spectrum of effects. Likewise, adverse effects become increasingly likely with higher doses and may include addiction, severe injury, or death ☠. These effects are listed and defined in detail within their own dedicated articles below:

Physical effects

-

- Sedation - In terms of energy level alterations, these substances have the potential to be extremely sedating and this often results in an overwhelmingly lethargic state. At higher levels, this causes users to suddenly feel as if they are extremely sleep deprived and have not slept for days, forcing them to sit down and generally feel as if they are constantly on the verge of passing out instead of engaging in physical activities. This sense of sleep deprivation increases proportional to dosage and eventually becomes powerful enough to force a person into complete unconsciousness.

- Muscle relaxation

- Physical euphoria

- Motor control loss

- Seizure suppression[16]

- Respiratory depression

- Dizziness

Paradoxical effects

-

Paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines such as increased seizures (in epileptics), aggression, increased anxiety, violent behavior, loss of impulse control, irritability and suicidal behavior sometimes occur (although they are rare in the general population, with an incidence rate below 1%).[17][18]

These paradoxical effects occur with greater frequency in recreational abusers, individuals with mental disorders, children, and patients on high-dosage regimes.[19][20]

Cognitive effects

-

- Anxiety suppression

- Disinhibition

- Cognitive euphoria - This effect is not consistently produced between individuals and seems to be highly dependent on personal factors. Some people do not report any euphoric effects following benzodiazepine use. When it does occur, it is typically described as mild to moderate and is commonly thought to occur at a higher rate in those with pre-existing anxiety issues. This may partly be the result of the immediateness in which the anxiety-relieving and disinhibiting effects are produced. While this effect may not be entirely consistent, many reports suggest that certain benzodiazepines are more reliable and effective at producing euphoria over others. [21]

- Memory suppression

- Analysis suppression

- Thought deceleration

- Emotion suppression - Although this compound primarily suppresses anxiety, it also dulls other emotions in a manner which is distinct but less intensive than that of antipsychotics.

- Delusions of sobriety - This is the false belief that one is perfectly sober despite obvious evidence to the contrary such as severe cognitive impairment and an inability to fully communicate with others. It most commonly occurs at heavy dosages.

- Compulsive redosing

- Dream potentiation

After effects

-

- Rebound anxiety - Rebound anxiety is a commonly observed effect with anxiety relieving substances like benzodiazepines. It typically corresponds to the total duration spent under the substance's influence along with the total amount consumed in a given period, an effect which can easily lend itself to cycles of dependence and addiction.

- Dream potentiation[22] or Dream suppression

- Residual sleepiness - While benzodiazepines can be used as an effective sleep-inducing aid, their effects may persist into the morning afterward, which may lead users to feeling "groggy" or "dull" for up to a few hours.

- Thought deceleration

- Thought disorganization

- Irritability

List of substituted benzodiazepines

Substituted 1,4-benzodiazepines

| Compound | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlordiazepoxide | NHCH3 | H | O | C6H5 | H | Cl | ||

| Bromazepam | H | =O | H | C5H4N | H | Br | ||

| Flubromazepam | H | =O | H | C6H4F | H | Br | ||

| Diazepam | CH3 | =O | H | C6H5 | H | Cl | ||

| Diclazepam | CH3 | =O | H | C6H4Cl | H | Cl | ||

| Lorazepam | H | =O | OH | C6H4Cl | H | Cl | ||

| Oxazepam | H | =O | OH | C6H5 | H | Cl | ||

| Temazepam | CH3 | =O | OH | C6H5 | H | Cl | ||

| Cinolazepam | CH2CH2≡N | =O | OH | C6H4F | H | Cl | ||

| Clonazepam | H | =O | H | C6H4Cl | H | NO2 | ||

| Flunitrazepam | CH3 | =O | H | C6H4F | H | NO2 | ||

| Meclonazepam | H | =O | CH3 | C6H4Cl | H | NO2 | ||

| Nifoxipam | H | =O | OH | C6H4F | H | NO2 | ||

| Alprazolam | C(CH3)=N- | =N- | H | C6H5 | H | Cl | ||

| Pyrazolam | C(CH3)=N- | =N- | H | C5H4N | H | Br | ||

| Flubromazolam | C(CH3)=N- | =N- | H | C6H4F | H | Br | ||

| Midazolam | C(CH3)=N- | =N- | H | C6H4F | H | Cl | ||

| Triazolam | C(CH3)=N- | =N- | H | C6H4Cl | H | Cl | ||

| Clonazolam | C(CH3)=N- | =N- | H | C6H4Cl | H | NO2 | ||

| Flunitrazolam | C(CH3)=N- | =N- | H | C6H4F | H | NO2 | ||

| Flumazenil | CH=N- | C(C3H5O2)- | H | CH3 | =O | H | F | |

| Bretazenil | CH=N- | C(C5H9O2)- | CH2CH2- | CH2- | =O | Br | H | |

| Clozapine | H | CH=CH- | CH=CH(Cl)- | C5H11N2 | H | H | ||

| Dibenzepin | CH3 | CH=CH- | CH=CH- | C4H10N | =O | H | H |

Equivalent dosages

The dosages below represent approximate equivalent dosages between various benzodiazepines in comparison to 10mg of diazepam.

The authors of this table specifically state that their equivalents differ from those used by other authors and "are firmly based on clinical experience during switch-over to diazepam at the start of withdrawal programs but may vary between individuals."[23]

| Prescription benzodiazepines | Half-life (Hours) [active metabolite] |

Approx. equivalent oral dosage (mg) |

Predominant effect (a= anxiolytic, c= anticonvulsant, h= hypnotic) |

| Alprazolam | 6-12 | 0.5 | a |

| Bromazepam | 10-20 | 5-6 | a |

| Chlordiazapoxide | 5-30 [36-200] | 25 | a |

| Clobazam | 12-60 | 20 | a, c |

| Clonazepam | 18-50 | 0.5 | a, c |

| Clorazepate | 20-179 [36-200] | 15 | a |

| Diazepam | 20-100 [36-200] | 10 | a, h, c |

| Estazolam | 10-24 | 1-2 | h |

| Etizolam | 4-12 | 1 | a |

| Flunitrazepam | 18-36 [36-200] | 1 | h |

| Flurazepam | 40-250 | 15-30 | h |

| Halazepam | 14 [30-200] | 20 | a |

| Ketazolam | 30-100 [36-200] | 15-30 | a |

| Loprazolam | 6-12 | 1-2 | h |

| Lorazepam | 10-20 | 1 | a, c |

| Lormetazepam | 10-12 | 1-2 | h |

| Medazepam | 36-200 | 10 | a |

| Nitrazepam | 15-38 | 10 | h |

| Nordazepam | 36-200 | 10 | a |

| Oxazepam | 4-15 | 20 | a |

| Prazepam | 29-224 [36-200] | 10-20 | a |

| Quazepam | 25-100 | 20 | h |

| Temazepam | 8-22 | 20 | h |

| Triazolam | 2 | 0.5 | h |

| Research chemicals | Half-life (Hours) [active metabolite] |

Approx. equivalent oral dosage (mg) |

Predominant effect (a= anxiolytic, c= anticonvulsant, h= hypnotic) |

| Clonazolam | ? | 0.2 | h |

| Deschloroetizolam | ~9-20 | 6 | a |

| Diclazepam | ~120 | 1 | a, h |

| Flualprazolam | ? | 0.2 | h |

| Flubromazepam | 106 | 4 | h |

| Flubromazolam | ? | 0.25 | h |

| Flunitrazolam | ? | 0.1 | h |

| Nifoxipam | 4-6 | 2 | a |

| Meclonazepam | ? | 5 | a, c |

| Metizolam | ~9-20 | 2 | a |

| Phenazepam | 60 | 1 | a |

| Pyrazolam | 17 | 1 | a |

| Z-drugs | Half-life (Hours) [active metabolite] |

Approx. equivalent oral dosage (mg) |

Predominant effect (a= anxiolytic, c= anticonvulsant, h= hypnotic) |

| Zaleplon | 2 | 20 | h |

| Zolpidem | 2 | 20 | h |

| Zopiclone | 5-6 | 15 | h |

| Eszopiclone | 6 | 3 | h |

Preparation methods

- Volumetric liquid dosing - If one's benzodiazepines are in powder form, they are unlikely to weigh out accurately without the most expensive of scales due to their extreme potency. To avoid this, one can dissolve the benzodiazepine volumetrically into a solution and dose it accurately based upon the methodological instructions linked within this tutorial here.

Medical uses

When combined with benzodiazepines, the visual hallucinations induced by hallucinogenic substances (particularly psychedelics) may significantly decrease along with any underlying anxiety that may be present.[citation needed]

Along with antipsychotics such as quetiapine (Seroquel), benzodiazepines are commonly administered in hospital settings to treat patients presenting symptoms of hallucinogen overdose or psychosis.[24]

Toxicity and harm potential

Benzodiazepines have a low toxicity relative to dose, and are considered to be effectively non-lethal on their own.[27] However, their potential potentially lethality increases significantly when mixed with depressants like alcohol or opioids.

It is strongly recommended that one use harm reduction practices when using this class of substances.

Tolerance and addiction potential

Benzodiazepines are known to be extremely physically and psychologically addictive.[citation needed]

Tolerance will develop to the sedative-hypnotic effects within a couple of days of continuous use.[28] After cessation, the tolerance returns to baseline in 7-14 days. Withdrawal symptoms or rebound symptoms may occur after ceasing one's usage abruptly following a few weeks or longer of steady dosing and may necessitate a gradual dose reduction.[29][30]

Overdose

Benzodiazepine overdose may occur with extremely high doses or, more commonly, when it is taken with other depressants. This risk is especially present with other GABAergic depressants, such as barbiturates and alcohol, since they work in a similar fashion but bind to distinct sites on the GABAA receptor, resulting in significant cross-potentiation.[citation needed]

Benzodiazepine overdose is a medical emergency that may lead to a coma, permanent brain injury or death if not treated promptly. Symptoms may include severe slurred speech, confusion, delusions, respiratory depression, and non-responsiveness. The user might seem like they are sleepwalking. The user is also more susceptible to consume more of the same or another substance due to their impaired judgement, which is typically not seen with other substances during overdose.

Benzodiazepine overdoses may be treated effectively in a hospital environment, with generally favorable outcomes. Care is primarily supportive in nature, although overdoses are sometimes treated with flumazenil, a GABAA antagonist[31] or additional procedures such as adrenaline injections if other substances are involved.[citation needed]

Discontinuation and withdrawal

Benzodiazepine discontinuation is notoriously difficult; it is potentially life-threatening for individuals using regularly to discontinue use without tapering their dose over a period of weeks. There is an increased risk of high blood pressure, seizures, and death.[32] Substances which lower the seizure threshold such as tramadol should be avoided during withdrawal.[citation needed] Abrupt discontinuation also causes rebound stimulation which presents as anxiety, insomnia and restlessness.[citation needed]

If one wishes to discontinue after a period of regular use, it is safest to reduce the dose each day by a very small amount for a couple of weeks until close to abstinence. If using a short half-life benzodiazepine such as alprazolam or etizolam, a longer acting variety such as diazepam or clonazepam can be substituted. Symptoms may still be present, but their severity will be reduced significantly.

For more information on tapering from benzodiazepines in a controlled manner, please see this guide. Small quantities of alcohol can also help to reduce the symptoms, but otherwise cannot be used as an effective tapering agent.

The duration and severity of withdrawal symptoms depend on a number of factors including the half-life of the substance used, tolerance and the duration of abuse. Major symptoms will usually start within just a few days after discontinuation and persist for around a week for shorter lasting benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines with longer half-lives will exhibit withdrawal symptoms with a slow onset and extended duration.[citation needed]

Dangerous interactions

Warning: Many psychoactive substances that are reasonably safe to use on their own can suddenly become dangerous and even life-threatening when combined with certain other substances. The following list provides some known dangerous interactions (although it is not guaranteed to include all of them).

Always conduct independent research (e.g. Google, DuckDuckGo, PubMed) to ensure that a combination of two or more substances is safe to consume. Some of the listed interactions have been sourced from TripSit.

- Depressants (1,4-Butanediol, 2M2B, alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, GHB/GBL, methaqualone, opioids) - This combination potentiates the muscle relaxation, amnesia, sedation, and respiratory depression caused by one another. At higher doses, it can lead to a sudden, unexpected loss of consciousness along with a dangerous amount of depressed respiration. There is also an increased risk of suffocating on one's vomit while unconscious. If nausea or vomiting occurs before a loss of consciousness, users should attempt to fall asleep in the recovery position or have a friend move them into it.

- Dissociatives - This combination can unpredictably potentiate the amnesia, sedation, motor control loss and delusions that can be caused by each other. It may also result in a sudden loss of consciousness accompanied by a dangerous degree of respiratory depression. If nausea or vomiting occurs before consciousness is lost, users should attempt to fall asleep in the recovery position or have a friend move them into it.

- Stimulants - Stimulants mask the sedative effect of depressants, which is the main factor most people use to gauge their level of intoxication. Once the stimulant effects wear off, the effects of the depressant will significantly increase, leading to intensified disinhibition, motor control loss, and dangerous black-out states. This combination can also potentially result in severe dehydration if one's fluid intake is not closely monitored. If choosing to combine these substances, one should strictly limit themselves to a pre-set schedule of dosing only a certain amount per hour until a maximum threshold has been reached.

See also

External links

- Benzodiazepines (Wikipedia)

- Benzodiazepines (Erowid Vault)

- Benzodiazepines (Drugs.com)

- TripSit Benzodiazepine Converter

Further reading

References

- ↑ Risks of Combining Depressants - TripSit

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Haefely, W. (29 June 1984). "Benzodiazepine interactions with GABA receptors". Neuroscience Letters. 47 (3): 201–206. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(84)90514-7. ISSN 0304-3940.

- ↑ Medicines used in generalized anxiety and sleep disorders. World Health Organization. 2009.

- ↑ Lann, M. A., Molina, D. K. (June 2009). "A fatal case of benzodiazepine withdrawal". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 30 (2): 177–179. doi:10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181875aa0. ISSN 1533-404X.

- ↑ Kahan, M., Wilson, L., Mailis-Gagnon, A., Srivastava, A., National Opioid Use Guideline Group (November 2011). "Canadian guideline for safe and effective use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain: clinical summary for family physicians. Appendix B-6: Benzodiazepine Tapering". Canadian Family Physician. 57 (11): 1269–1276. ISSN 1715-5258.

- ↑ Sternbach LH (1979). "The benzodiazepine story". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 22 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1021/jm00187a001. PMID 34039.

During this cleanup operation, my co-worker, Earl Reeder, drew my attention to a few hundred milligrams of two products, a nicely crystalline base and its hydrochloride. Both the base, which had been prepared by treating the quinazoline N-oxide 11 with methylamine, and its hydrochloride had been made sometime in 1955. The products were not submitted for pharmacological testing at that time because of our involvement with other problems

- ↑ Miller NS, Gold MS (1990). "Benzodiazepines: reconsidered". Adv Alcohol Subst Abuse. 8 (3–4): 67–84. doi:10.1300/J251v08n03_06. PMID 1971487.

- ↑ Shorter E (2005). "Benzodiazepines". A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry. Oxford University Press. pp. 41–2. ISBN 0-19-517668-5.

- ↑ King MB (1992). "Is there still a role for benzodiazepines in general practice?". Br J Gen Pract. 42 (358): 202–5. PMC 1372025

. PMID 1389432.

. PMID 1389432.

- ↑ Peart R (1999-06-01). "Memorandum by Dr Reg Peart". Minutes of Evidence. Select Committee on Health, House of Commons, UK Parliament. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ Lader M (2008). "Effectiveness of benzodiazepines: do they work or not?". Expert Rev Neurother (PDF). 8 (8): 1189–91. doi:10.1586/14737175.8.8.1189. PMID 18671662.

- ↑ Jufe GS (Jul–Aug 2007). "[New hypnotics: perspectives from sleep physiology]". Vertex. 18 (74): 294–9. PMID 18265473.

- ↑ Lemmer B (2007). "The sleep–wake cycle and sleeping pills". Physiol Behav. 90 (2–3): 285–93. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.09.006. PMID 17049955.

- ↑ McLean, M. J., Macdonald, R. L. (February 1988). "Benzodiazepines, but not beta carbolines, limit high frequency repetitive firing of action potentials of spinal cord neurons in cell culture". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 244 (2): 789–795. ISSN 0022-3565.

- ↑ Narimatsu, E., Niiya, T., Kawamata, M., Namiki, A. (June 2006). "[The mechanisms of depression by benzodiazepines, barbiturates and propofol of excitatory synaptic transmissions mediated by adenosine neuromodulation]". Masui. The Japanese Journal of Anesthesiology. 55 (6): 684–691. ISSN 0021-4892.

- ↑ Woolley, C. S., Schwartzkroin, P. A. (August 1998). "Hormonal Effects on the Brain". Epilepsia. 39 (s8): S2–S8. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb02601.x. ISSN 0013-9580.

- ↑ Saïas, T., Gallarda, T. (September 2008). "[Paradoxical aggressive reactions to benzodiazepine use: a review]". L’Encephale. 34 (4): 330–336. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2007.05.005. ISSN 0013-7006.

- ↑ Paton, C. (December 2002). "Benzodiazepines and disinhibition: a review". Psychiatric Bulletin. 26 (12): 460–462. doi:10.1192/pb.26.12.460. ISSN 0955-6036.

- ↑ Bond, A. J. (1 January 1998). "Drug- Induced Behavioural Disinhibition". CNS Drugs. 9 (1): 41–57. doi:10.2165/00023210-199809010-00005. ISSN 1179-1934.

- ↑ Drummer, O. H. (February 2002). "Benzodiazepines - Effects on Human Performance and Behavior". Forensic Science Review. 14 (1–2): 1–14. ISSN 1042-7201.

- ↑ Griffin, C. E., Kaye, A. M., Bueno, F. R., Kaye, A. D. (2013). "Benzodiazepine Pharmacology and Central Nervous System–Mediated Effects". The Ochsner Journal. 13 (2): 214–223. ISSN 1524-5012.

- ↑ Goyal, S. (14 March 1970). "Drugs and dreams". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 102 (5): 524. ISSN 0008-4409.

- ↑ benzo.org.uk : Benzodiazepine Equivalence Table

- ↑ Benzodiazepines alone or in combination with antipsychotic drugs for acute psychosis

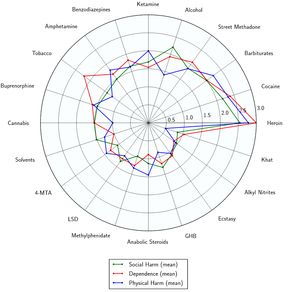

- ↑ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283

. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. Unknown parameter

. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. Unknown parameter |s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ Nutt, D., King, L. A., Saulsbury, W., Blakemore, C. (24 March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. ISSN 0140-6736.

- ↑ Mandrioli, R., Mercolini, L., Raggi, M. A. (October 2008). "Benzodiazepine metabolism: an analytical perspective". Current Drug Metabolism. 9 (8): 827–844. doi:10.2174/138920008786049258. ISSN 1389-2002.

- ↑ Janicak, P. G., Marder, S. R., Pavuluri, M. N. (25 October 2010). Principles and Practice of Psychopharmacotherapy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781605475653.

- ↑ Verster, J. C., Volkerts, E. R. (7 June 2006). "Clinical Pharmacology, Clinical Efficacy, and Behavioral Toxicity of Alprazolam: A Review of the Literature". CNS Drug Reviews. 10 (1): 45–76. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2004.tb00003.x. ISSN 1080-563X.

- ↑ Galanter, M., Kleber, H. D. (2008). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment. American Psychiatric Pub. ISBN 9781585622764.

- ↑ Hoffman, E. J., Warren, E. W. (September 1993). "Flumazenil: a benzodiazepine antagonist". Clinical Pharmacy. 12 (9): 641–656; quiz 699–701. ISSN 0278-2677.

- ↑ Lann, M. A., Molina, D. K. (June 2009). "A fatal case of benzodiazepine withdrawal". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 30 (2): 177–179. doi:10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181875aa0. ISSN 1533-404X.