Synthetic cannabinoid

Synthetic Cannabinoids: Over 1,000 hospitalized, 94 deaths linked to three types

Multiple synthetic cannabinoids pose serious health risks. MDMB-FUBINACA alone is linked to over 1,000 hospitalizations and 40 deaths, primarily in Russia and Belarus. Across Europe, MDMB-CHMICA and 5F-ADB have caused a combined 54 deaths between 2014 and 2017.

Synthetic cannabinoids (also known as synthetic marijuana, noids, herbal incense, K2, or spice) are a class of compounds that bind to cannabinoid receptors to produce cannabis-like subjective effects. Most synthetic cannabinoids are analogs of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main active compound of cannabis, while non-psychoactive cannabinoids such as CBD are less well studied. Like THC, most synthetic cannabinoids bind to the same cannabinoid receptors in the brain and are often sold as legal alternatives.

Synthetic cannabinoids are usually sprayed or soaked into dry herbs to look more like marijuana,[1] but pure powder is also available for sale on online research chemical markets. They are commonly smoked or vaporized to achieve a quick onset of effects. They are also orally active when dissolved in a lipid, which can increase the duration significantly. Most are insoluble in water but dissolve in ethanol and lipids.

Unlike cannabis, the chronic abuse of synthetic cannabinoids has been associated with multiple deaths and more dangerous side effects and toxicity in general. Therefore, it is strongly discouraged to take these substances for extended periods of time or in high doses. Additionally, many synthetic cannabinoids have almost little to no human research and some pose more severe health risks than others. It is highly advised to use harm reduction practices if using these substances.

Examples

Herb blends

Popular herb blends include K2[2] and Spice,[3] both of which are generic trademarks used for any synthetic cannabinoid product. Synthetic cannabinoids are often marketed as "herbal incense" and "herbal smoking blends." Pre-mixed, branded blends (like Spice and K2) are more dangerous than pure powder because the specific chemicals and dosages are usually unlisted as well as the potential of inconsistent areas of dense powder, leading to an overdose.

Many people have been hospitalized or suffered negative symptoms believing they are comparable to cannabis in potency, harm potential, and effects. This is not the case, and they should be avoided in favour of pure powder.

Indazolecarboxamides

Indolecarboxamides

Indolecarboxylates

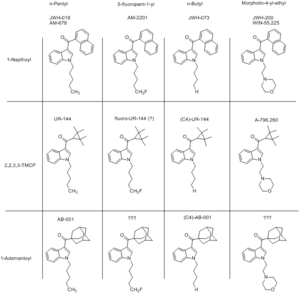

Naphthoylindoles

Naphthoylindazoles

Tetramethylcyclopropanoylindoles

Comprehensive list

For a comprehensive list of known synthetic cannabinoid derivatives, /r/Drugs/wiki has published a respectable directory of names and links to further information.

Toxicity and harm potential

Unlike cannabis, there have been multiple deaths[4][5][6][7][8][9][10] associated with the repeated abuse of synthetic cannabinoids as well as serious side effects resulting from its long-term use.[11][12][13] Therefore, it is strongly discouraged to take this substance for extended periods of time or in excessive doses. Compared to cannabis and its active cannabinoid THC, the adverse effects are often much more severe and can include high blood pressure, increased heart rate, heart attacks,[14][15] agitation,[16] vomiting,[17][18][19] hallucinations,[20] psychosis,[21][22][16][23] seizures,[24][25][26] and convulsions[27][28] as well as many others. Sixteen cases of acute kidney injury resulting from synthetic cannabinoid abuse have been reported.[29] JWH-018 has also been associated with strokes in two healthy adults.[30]

It should be noted that pre-mixed, branded blends (like Spice and K2) are more dangerous than pure powder because the specific chemicals and dosages are usually unlisted as well as the potential of inconsistent areas of dense powder, leading to an overdose. As synthetic cannabinoids are active in the milligram range (with below 5mg being a common dose), it is important to use proper precautions when dosing to avoid a negative experience.

These more severe adverse effects in contrast to use of marijuana are believed to stem from the fact that many of the synthetic cannabinoids are full agonists to the cannabinoid receptors, CB1R and CB2R, compared to THC which is only a partial agonist and thus not able to saturate and activate all of the receptor population no matter of dose and resulting concentration.[31]

It is strongly recommended that one use harm reduction practices when using these drugs.

Deaths

Unlike cannabis, there have been multiple deaths associated with the chronic abuse of synthetic cannabinoid use.[4][5]

- MDMB-FUBINACA: There have been a large number of reported cases of deaths and hospitalizations in relation to this synthetic cannabinoid, mainly in Russia and Belarus. MDMB-FUBINACA was first reported in 2014 and quickly gained a reputation as the most deadly synthetic cannabinoid drug sold by 2015.[32] Up to 700 hospitalisations and 25 deaths were initially linked to MDMB-FUBINACA in media and government reports, and subsequent testing confirmed that at least 1000 hospitalisations and 40 deaths had occurred as a consequence of intoxication by MDMB-FUBINACA as of March 2015.[33][34]

- MDMB-CHMICA: Seventy-one serious adverse events, including 42 acute intoxications and 29 deaths (Germany (5), Hungary (3), Poland (1), Sweden (9), United Kingdom (10), Norway (1)) that occurred in nine European countries between 2014 and 2016 have been associated with MDMB-CHMICA.[35][36][37][38][39]

- 5F-MDMB-PINACA has been associated with 25 deaths in Europe between 2015 and 2017.[40]

- 5F-PB-22: In addition, five deaths have been associated with the use of 5F-PB-22 in the United States[7]

- AB-FUBINACA has also been associated with multiple hospitalizations and deaths due to its use.[10]

Psychosis

Like THC, prolonged usage of synthetic cannabinoids may increase one's disposition to mental illness and psychosis[22], particularly in vulnerable individuals with risk factors for psychotic illnesses (like a past or family history of schizophrenia).[41][42][16] It is recommended that individuals with risk factors for psychotic disorders not use synthetic cannabinoids.[43]

In contrast to most other recreational drugs, the dramatic psychotic state induced by the use of synthetic cannabinoids has been reported in multiple cases to persist for several weeks, and in one case for seven months after complete cessation of drug use.[44] It has been suggested that the lack of an antipsychotic chemical (the cannabidiol found in natural cannabis) may make synthetic cannabis more likely to induce psychosis than natural cannabis.[23] As with the acute adverse physical effects, this increase in the risk of psychotic side effects has also been connected to full rather than partial agonism.[45]

Toxicity

Although there is no valid data on the toxicity of synthetic cannabinoids so far, there is concern that the naphthalene group found in THJ-018 and some other synthetic cannabinoids may be toxic or carcinogenic.[46][47][48][49]

Addiction potential

When compared to cannabis, the chronic use of synthetic cannabinoids can be considered more moderately addictive with a high potential for abuse and is capable of causing psychological dependence among certain users. When addiction has developed, cravings and withdrawal effects may occur if a person suddenly stops their usage.[50]

Dangerous interactions

Warning: Many psychoactive substances that are reasonably safe to use on their own can suddenly become dangerous and even life-threatening when combined with certain other substances. The following list provides some known dangerous interactions (although it is not guaranteed to include all of them).

Always conduct independent research (e.g. Google, DuckDuckGo, PubMed) to ensure that a combination of two or more substances is safe to consume. Some of the listed interactions have been sourced from TripSit.

- 2C-T-x

- 2C-x

- 5-MeO-xxT

- Amphetamines - Stimulants increase anxiety levels and the risk of thought loops which can lead to negative experiences

- aMT

- Cocaine - Stimulants increase anxiety levels and the risk of thought loops which can lead to negative experiences

- DMT

- DOx

- Lithium - Lithium is commonly prescribed in the treatment of bipolar disorder; however, there is a large body of anecdotal evidence that suggests taking it with cannabinoids can significantly increase the risk of psychosis and seizures. As a result, this combination should be strictly avoided.

- LSD

- Mescaline

- Mushrooms

- 25x-NBOMe

See also

External links

- Synthetic cannabinoids (Wikipedia)

- Cannabinoids & Synthetic Cannabinoids (Erowid Vault)

- Spice-Like Products (Erowid Vault)

References

- ↑ Synthetic Marijuana

- ↑ Carmichael, M. (2010), K2: Scary Drug or Another Drug Scare?

- ↑ "What's the buzz?: Synthetic marijuana, K2, Spice, JWH-018 : Terra Sigillata". Scienceblogs.com. | http://scienceblogs.com/terrasig/2010/02/09/k2-spice-jwh018-marijuana/

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Brents, L. K., Reichard, E. E., Zimmerman, S. M., Moran, J. H., Fantegrossi, W. E., Prather, P. L. (2011). "Phase I hydroxylated metabolites of the K2 synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 retain in vitro and in vivo cannabinoid 1 receptor affinity and activity". PloS One. 6 (7): e21917. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021917. ISSN 1932-6203.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Coroner: Lamar Jack ingested chemical found in fake marijuana before he died » Anderson Independent Mail, 2013

- ↑ Colorado probes three deaths possibly linked to synthetic marijuana, 2013

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Synthetic cannabinoids in Europe

- ↑ Westin, A. A., Frost, J., Brede, W. R., Gundersen, P. O. M., Einvik, S., Aarset, H., Slørdal, L. (9 September 2015). "Sudden Cardiac Death Following Use of the Synthetic Cannabinoid MDMB-CHMICA". Journal of Analytical Toxicology: bkv110. doi:10.1093/jat/bkv110. ISSN 0146-4760.

- ↑ Adamowicz, P. (April 2016). "Fatal intoxication with synthetic cannabinoid MDMB-CHMICA". Forensic Science International. 261: e5–e10. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.02.024. ISSN 0379-0738.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Trecki, J., Gerona, R. R., Schwartz, M. D. (9 July 2015). "Synthetic Cannabinoid–Related Illnesses and Deaths". New England Journal of Medicine. 373 (2): 103–107. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1505328. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ↑ Vardakou, I., Pistos, C., Spiliopoulou, C. (1 September 2010). "Spice drugs as a new trend: mode of action, identification and legislation". Toxicology Letters. 197 (3): 157–162. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.06.002. ISSN 1879-3169.

- ↑ Auwärter, V., Dresen, S., Weinmann, W., Müller, M., Pütz, M., Ferreirós, N. (May 2009). "'Spice' and other herbal blends: harmless incense or cannabinoid designer drugs?". Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 44 (5): 832–837. doi:10.1002/jms.1558. ISSN 1076-5174.

- ↑ Kronstrand, R., Roman, M., Andersson, M., Eklund, A. (1 October 2013). "Toxicological Findings of Synthetic Cannabinoids in Recreational Users". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 37 (8): 534–541. doi:10.1093/jat/bkt068. ISSN 0146-4760.

- ↑ Mir, A., Obafemi, A., Young, A., Kane, C. (1 December 2011). "Myocardial Infarction Associated With Use of the Synthetic Cannabinoid K2". Pediatrics. 128 (6): e1622–e1627. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3823. ISSN 0031-4005.

- ↑ McIlroy, G., Ford, L., Khan, J. M. (16 January 2016). "Acute myocardial infarction, associated with the use of a synthetic adamantyl-cannabinoid: a case report". BMC Pharmacology & Toxicology. 17: 2. doi:10.1186/s40360-016-0045-1. ISSN 2050-6511.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Vearrier, D., Osterhoudt, K. C. (June 2010). "A Teenager With Agitation: Higher Than She Should Have Climbed". Pediatric Emergency Care. 26 (6): 462–465. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181e4f416. ISSN 0749-5161.

- ↑ JWH-018 - Erowid Exp - “Extreme Nausea, Incoherent”

- ↑ Spice - Erowid Exp - “Playing With Fire”

- ↑ Spice and Synthetic Cannabinoids ('Drill’) - Erowid Exp - “Non-Allergic Adverse Reaction”

- ↑ published, J. B. (2010), Fake Weed, Real Drug: K2 Causing Hallucinations in Teens

- ↑ Every-Palmer, S. (October 2010). "Warning: legal synthetic cannabinoid-receptor agonists such as JWH-018 may precipitate psychosis in vulnerable individuals". Addiction (Abingdon, England). 105 (10): 1859–1860. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03119.x. ISSN 1360-0443.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Arseneault, L., Cannon, M., Witton, J., Murray, R. M. (February 2004). "Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 184 (2): 110–117. doi:10.1192/bjp.184.2.110. ISSN 0007-1250.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Müller, H., Sperling, W., Köhrmann, M., Huttner, H. B., Kornhuber, J., Maler, J.-M. (May 2010). "The synthetic cannabinoid Spice as a trigger for an acute exacerbation of cannabis induced recurrent psychotic episodes". Schizophrenia Research. 118 (1–3): 309–310. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.12.001. ISSN 1573-2509.

- ↑ JWH-018 - Erowid Exp - “Most Insane Hour of My Life”

- ↑ AM-2201 - Erowid Exp - “The Night My Brain Caved”

- ↑ Products - Spice and Synthetic Cannabinoids (“Apocalypse”?) - Erowid Exp - “Next-Night Seizures”

- ↑ Products - Spice and Synthetic Cannabinoids ('Smiley Dog’) - Erowid Exp - “Never Again”

- ↑ Schneir, A. B., Baumbacher, T. (March 2012). "Convulsions associated with the use of a synthetic cannabinoid product". Journal of Medical Toxicology: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology. 8 (1): 62–64. doi:10.1007/s13181-011-0182-2. ISSN 1937-6995.

- ↑ Acute Kidney Injury Associated with Synthetic Cannabinoid Use — Multiple States, 2012

- ↑ Freeman, M. J., Rose, D. Z., Myers, M. A., Gooch, C. L., Bozeman, A. C., Burgin, W. S. (10 December 2013). "Ischemic stroke after use of the synthetic marijuana "spice"". Neurology. 81 (24): 2090–2093. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000437297.05570.a2. ISSN 1526-632X.

- ↑ Fantegrossi, W. E., Moran, J. H., Radominska-Pandya, A., Prather, P. L. (27 February 2014). "Distinct pharmacology and metabolism of K2 synthetic cannabinoids compared to Δ(9)-THC: mechanism underlying greater toxicity?". Life Sciences. 97 (1): 45–54. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2013.09.017. ISSN 1879-0631.

- ↑ Shevyrin V, Melkozerov V, Nevero A, Eltsov O, Shafran Y, Morzherin Y, Lebedev AT (August 2015). "Identification and analytical characteristics of synthetic cannabinoids with an indazole-3-carboxamide structure bearing a N-1-methoxycarbonylalkyl group". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 407 (21): 6301–15. doi:10.1007/s00216-015-8612-7. PMID 25893797. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ "Выступление председателя ГАК, директора ФСКН России В.П. Иванова на заседании ГАК 6 октября 2014 г" (in Russian). Federal Drug Control Service of the Russian Federation. 6 October 2014. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ I. Bulygina (21 October 2014). "Clinical presentations of intoxication by new psychoactive compound MDMB(N)-Bz-F. Thesis of The II Scientific and Practical Seminar 'Methodical, Organizational and Law Problems of Chemical and Toxicological Laboratories of Narcological Services', Moscow" (in Russian). Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedEMCDDA - ↑ "Derby legal high confusion prompts police warning". BBC. 29 April 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ "Drug Alert: Dangerous Synthetic Cannabinoid MMB-CHMINACA Causing Hospitalizations, Deaths in Europe". TalkingDrugs. 2 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ↑ Westin AA, Frost J, Brede WR, Gundersen PO, Einvik S, Aarset H, Slørdal L (February 2016). "Sudden Cardiac Death Following Use of the Synthetic Cannabinoid MDMB-CHMICA". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 40 (1): 86–7. doi:10.1093/jat/bkv110

. PMID 26353925.

. PMID 26353925.

- ↑ Adamowicz P (April 2016). "Fatal intoxication with synthetic cannabinoid MDMB-CHMICA". Forensic Science International. 261: e5–10. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.02.024. PMID 26934903.

- ↑ Template:Cite report

- ↑ Every-Palmer, S. (September 2011). "Synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 and psychosis: An explorative study". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 117 (2–3): 152–157. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.012. ISSN 0376-8716.

- ↑ Schneir, A. B., Cullen, J., Ly, B. T. (1 March 2011). ""Spice" Girls: Synthetic Cannabinoid Intoxication". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 40 (3): 296–299. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.10.014. ISSN 0736-4679.

- ↑ Every-Palmer, S. (1 September 2011). "Synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 and psychosis: an explorative study". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 117 (2–3): 152–157. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.012. ISSN 1879-0046.

- ↑ Hurst, D., Loeffler, G., McLay, R. (October 2011). "Psychosis associated with synthetic cannabinoid agonists: a case series". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 168 (10): 1119. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010176. ISSN 1535-7228.

- ↑ Murray, R. M., Quigley, H., Quattrone, D., Englund, A., Di Forti, M. (October 2016). "Traditional marijuana, high-potency cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids: increasing risk for psychosis". World Psychiatry. 15 (3): 195–204. doi:10.1002/wps.20341. ISSN 1723-8617.

- ↑ Naphthalene - United States Environmental Protection Agency | http://www.epa.gov/ttn/atw/hlthef/naphthal.html

- ↑ Lin, C. Y., Wheelock, A. M., Morin, D., Baldwin, R. M., Lee, M. G., Taff, A., Plopper, C., Buckpitt, A., Rohde, A. (16 June 2009). "Toxicity and metabolism of methylnaphthalenes: comparison with naphthalene and 1-nitronaphthalene". Toxicology. 260 (1–3): 16–27. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2009.03.002. ISSN 1879-3185.

- ↑ Synthetic cannabinoids in herbal products (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime) | https://www.unodc.org/documents/scientific/Synthetic_Cannabinoids.pdf

- ↑ Morris, H. (2010), HAMILTON MORRIS?: NAPTHALENE IS SO OVER

- ↑ Zimmermann, U. S., Winkelmann, P. R., Pilhatsch, M., Nees, J. A., Spanagel, R., Schulz, K. (July 2009). "Withdrawal Phenomena and Dependence Syndrome After the Consumption of "Spice Gold"". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 106 (27): 464–467. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0464. ISSN 1866-0452.