Talk:Chlordiazepoxide

This page has not been fully approved by the PsychonautWiki administrators. It may contain incorrect information, particularly with respect to dosage, duration, subjective effects, toxicity and other risks. It may also not meet PW style and grammar standards. |

Fatal overdose may occur when benzodiazepines are combined with other depressants such as opiates, barbiturates, gabapentinoids, thienodiazepines, alcohol or other GABAergic substances.[1]

It is strongly discouraged to combine these substances, particularly in common to heavy doses.

| Summary sheet: Chlordiazepoxide |

| Chlordiazepoxide | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Nomenclature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common names | Librium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Substitutive name | Chlordiazepoxide | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systematic name | 7-chloro-2-methylamino-5-phenyl-3H-1,4-benzodiazepin-4-oxide | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Class Membership | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Psychoactive class | Depressant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chemical class | Benzodiazepine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Routes of Administration | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chlordiazepoxide (also known as Librium) is a depressant substance of the benzodiazepine class. Its mechanism of action is to increase the effects of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA.

Chlordiazepoxide is notable among benzodiazepines for having a relatively long duration of action, compounded by the even longer half-life of its active metabolites, primarily nordiazepam (up to 300 hours). It is indicated for the short-term treatment of debilitating anxiety and alcohol withdrawal. Compared to other benzodiazepines, chlordiazepoxide is not particularly potent and has a long onset. Hence, it is seldom used as a PRN anxiolytic (given its prolonged onset) or for its other indications (given its low efficacy compared to other benzodiazepines).

Subjective effects include anxiety suppression, sedation, and muscle relaxation.[2] Its usage is rare, and limited mostly to managing symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. Given its particularly strong hypnotic and amnesic effects, infrequent prescription, and prolonged onset, it is not commonly used recreationally.

Chlordiazepoxide is considered to have low toxicity.[citation needed] It has moderate abuse potential, given its long duration of action. Recreational use is uncommon, as it is not often prescribed outside the context of detoxification and withdrawal management. It still however produces physical and psychological symptoms of dependence with extended use. Additionally, it can contribute to death by respiratory depression if combined with alcohol, opiates, and other depressants. It is highly advised to use harm reduction practices if using this substance.

It should be noted that the sudden discontinuation of benzodiazepines can be potentially dangerous or life-threatening for individuals using regularly for extended periods of time, sometimes resulting in seizures or death.[3] It is highly recommended to taper one's dose by gradually lowering the amount taken each day for a prolonged period of time instead of stopping abruptly.[4]

History and culture

This History and culture section is a stub. As a result, it may contain incomplete or wrong information. You can help by expanding it. |

Chlordiazepoxide was accidentally discovered in 1957. and was found to have sedative and hypnotic effects. This discovery led to its marketing in 1960 and the development of the benzodiazepine class of drugs. Six years later, in 1963, diazepam (which is much more widely used than chlordiazepoxide), was created, kicking off a cascade of benzodiazepines. Initially met with widespread approval due to their efficacy, benzodiazepines were later restricted in light of evidence of their potential for recreational usage and liability to cause dependence and addiction.[5]

Chemistry

This chemistry section is incomplete. You can help by adding to it. |

Pharmacology

|

This pharmacology section is incomplete. You can help by adding to it. |

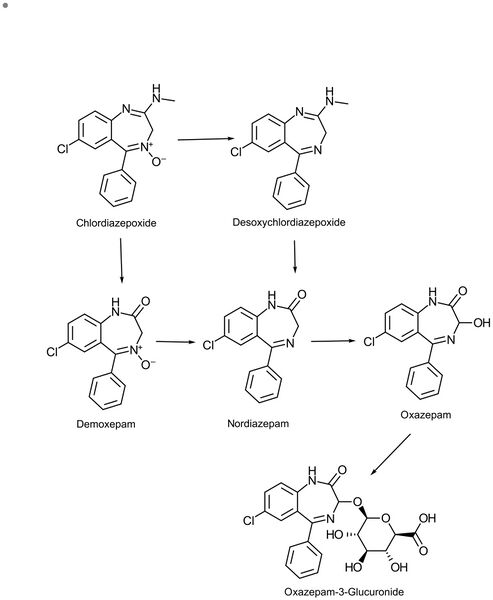

Chlordiazepoxide is a prodrug to Nordiazepam which functions as a partial agonist at ω1 and ω2 Benzodiazepine Receptors which is an allosteric site of the GABAa receptor. The conformational change as a result of van der waals Forces allows for roughly a 300% increase in GABAa receptor activation. Nordiazepam is a metabolite of many Benzodiazepines which is slowly metabolized to Oxazepam (full agonist activity) and subsequently conjugated.

Subjective effects

|

This subjective effects section is a stub. As such, it is still in progress and may contain incomplete or wrong information. You can help by expanding or correcting it. |

Disclaimer: The effects listed below cite the Subjective Effect Index (SEI), an open research literature based on anecdotal user reports and the personal analyses of PsychonautWiki contributors. As a result, they should be viewed with a healthy degree of skepticism.

It is also worth noting that these effects will not necessarily occur in a predictable or reliable manner, although higher doses are more liable to induce the full spectrum of effects. Likewise, adverse effects become increasingly likely with higher doses and may include addiction, severe injury, or death ☠.

Physical effects

-

- Sedation

- Muscle relaxation

- Motor control loss

- Respiratory depression

- Dizziness

- Seizure suppression

- Physical euphoria - This effect is often only present in individuals who are naturally anxious, and, when it presents itself, is tame in comparison to more commonly used euphoriants.

Visual effects

Paradoxical effects

-

Paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines such as increased seizures (in epileptics), aggression, increased anxiety, violent behavior, loss of impulse control, irritability and suicidal behavior sometimes occur (although they are rare in the general population, with an incidence rate below 1%).[6][7]

These paradoxical effects occur with greater frequency in recreational abusers, individuals with mental disorders, children, and patients on high-dosage regimes.[8][9]

Cognitive effects

-

The most prominent of these cognitive effects generally include:

- Anxiety suppression

- Disinhibition

- Delusions of sobriety - This is the false belief that one is perfectly sober despite obvious evidence to the contrary such as severe cognitive impairment and an inability to fully communicate with others. It most commonly occurs at heavy dosages.

- Thought deceleration

- Analysis suppression

- Amnesia

- Memory suppression

- Compulsive redosing

- Emotion suppression - Although this compound primarily suppresses anxiety, it also dulls other emotions in a manner which is distinct but less intensive than with that of antipsychotics.

- Motivation suppression

- Language suppression - Chlordiazepoxide & most benzodiazepines are known to cause slurred speech and difficulty communicating words in a clear fashion.

After effects

-

- Rebound anxiety - Rebound anxiety is a commonly observed effect with anxiety relieving substances like benzodiazepines. It typically corresponds to the total duration spent under the substance's influence along with the total amount consumed in a given period, an effect which can easily lend itself to cycles of dependence and addiction.

- Dream potentiation[10] or Dream suppression

- Residual sleepiness - While benzodiazepines can be used as an effective sleep-inducing aid, their effects may persist into the morning afterward, which may lead users to feeling "groggy" or "dull" for up to a few hours.

- Thought deceleration

- Thought disorganization

- Irritability

Experience reports

There are currently 0 experience reports which describe the effects of this substance in our experience index.

Additional experience reports can be found here:

Toxicity and harm potential

|

This toxicity and harm potential section is a stub. As a result, it may contain incomplete or even dangerously wrong information! You can help by expanding upon or correcting it. |

Chlordiazepoxide has a low toxicity relative to dose.[2] However, it is potentially lethal when mixed with depressants like alcohol or opioids.

It is strongly recommended that one use harm reduction practices, such as volumetric dosing, when using this substance to ensure the administration of the intended dose.

Lethal dosage

Chlordiazepoxide has a high LD50. Alone, fatal benzodiazepine overdoses occur only with extraordinarily high dosages, but when combined with other depressants, this threshold is lowered significantly.

Tolerance and addiction potential

Like other benzodiazepines, chlordiazepoxide is liable to cause physical dependence and addiction in a manner directly correlated to how long the substance is used for and the dosage at which the substance is used. Long-term treatment with benzodiazepines is not suggested, as it often results in a physical dependence that presents uncomfortable, if not life-threatening, withdrawal symptoms.

Dangerous interactions

|

This dangerous interactions section is a stub. As such, it may contain incomplete or invalid information. You can help by expanding upon or correcting it. |

Warning: Many psychoactive substances that are reasonably safe to use on their own can suddenly become dangerous and even life-threatening when combined with certain other substances. The following list provides some known dangerous interactions (although it is not guaranteed to include all of them).

Always conduct independent research (e.g. Google, DuckDuckGo, PubMed) to ensure that a combination of two or more substances is safe to consume. Some of the listed interactions have been sourced from TripSit.

- Depressants (1,4-Butanediol, 2-methyl-2-butanol, alcohol, barbiturates, GHB/GBL, methaqualone, opioids) - This combination can result in dangerous or even fatal levels of respiratory depression. These substances potentiate the muscle relaxation, sedation and amnesia caused by one another and can lead to unexpected loss of consciousness at high doses. There is also an increased risk of vomiting during unconsciousness and death from the resulting suffocation. If this occurs, users should attempt to fall asleep in the recovery position or have a friend move them into it.

- Dissociatives - This combination can result in an increased risk of vomiting during unconsciousness and death from the resulting suffocation. If this occurs, users should attempt to fall asleep in the recovery position or have a friend move them into it.

- Stimulants - It is dangerous to combine benzodiazepines with stimulants due to the risk of excessive intoxication. Stimulants decrease the sedative effect of benzodiazepines, which is the main factor most people consider when determining their level of intoxication. Once the stimulant wears off, the effects of benzodiazepines will be significantly increased, leading to intensified disinhibition as well as other effects. If combined, one should strictly limit themselves to only dosing a certain amount of benzodiazepines per hour. This combination can also potentially result in severe dehydration if hydration is not monitored.

Legal status

|

This legality section is a stub. As such, it may contain incomplete or wrong information. You can help by expanding it. |

Internationally, chlordiazepoxide is a Schedule IV controlled drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[12] Chlordiazepoxide is regulated in most countries as a prescription drug.

See also

External links

(List along order below)

- SUBSTANCE (Wikipedia)

- SUBSTANCE (Erowid Vault)

- SUBSTANCE ([PiHKAL or TiHKAL] / Isomer Design)

Literature

- APA formatted reference

Please see the citation formatting guide if you need assistance properly formatting citations.

References

- ↑ Risks of Combining Depressants - TripSit

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mandrioli, R., Mercolini, L., Raggi, M. A. (October 2008). "Benzodiazepine metabolism: an analytical perspective". Current Drug Metabolism. 9 (8): 827–844. doi:10.2174/138920008786049258. ISSN 1389-2002.

- ↑ Lann, M. A., Molina, D. K. (June 2009). "A fatal case of benzodiazepine withdrawal". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 30 (2): 177–179. doi:10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181875aa0. ISSN 1533-404X.

- ↑ Kahan, M., Wilson, L., Mailis-Gagnon, A., Srivastava, A. (November 2011). "Canadian guideline for safe and effective use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain. Appendix B-6: Benzodiazepine Tapering". Canadian Family Physician. 57 (11): 1269–1276. ISSN 0008-350X.

- ↑ Cooper JR, Bloom FE, Roth RH (January 15, 1996). The Complete Story of the Benzodiazepines (seventh ed.). USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510399-8. Archived from the original on 2008-03-15. Retrieved 7 Apr 2008. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Saïas, T., Gallarda, T. (September 2008). "[Paradoxical aggressive reactions to benzodiazepine use: a review]". L’Encephale. 34 (4): 330–336. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2007.05.005. ISSN 0013-7006.

- ↑ Paton, C. (December 2002). "Benzodiazepines and disinhibition: a review". Psychiatric Bulletin. 26 (12): 460–462. doi:10.1192/pb.26.12.460. ISSN 0955-6036.

- ↑ Bond, A. J. (1 January 1998). "Drug- Induced Behavioural Disinhibition". CNS Drugs. 9 (1): 41–57. doi:10.2165/00023210-199809010-00005. ISSN 1179-1934.

- ↑ Drummer, O. H. (February 2002). "Benzodiazepines - Effects on Human Performance and Behavior". Forensic Science Review. 14 (1–2): 1–14. ISSN 1042-7201.

- ↑ Goyal, S. (14 March 1970). "Drugs and dreams". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 102 (5): 524. ISSN 0008-4409.

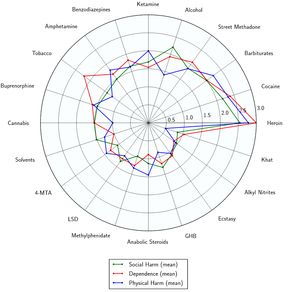

- ↑ Nutt, D., King, L. A., Saulsbury, W., Blakemore, C. (24 March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. ISSN 0140-6736.

- ↑ International Narcotics Control Board (2003) | http://infoespai.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/green.pdf