Pyrazolam

Fatal overdose may occur when benzodiazepines are combined with other depressants such as opiates, barbiturates, gabapentinoids, thienodiazepines, alcohol or other GABAergic substances.[1]

It is strongly discouraged to combine these substances, particularly in common to heavy doses.

| Summary sheet: Pyrazolam |

| Pyrazolam | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Nomenclature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common names | Pyrazolam | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systematic name | 8-bromo-1-methyl-6-(pyridin-2-yl)-4H-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]benzodiazepine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Class Membership | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Psychoactive class | Depressant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chemical class | Benzodiazepine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Routes of Administration | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interactions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pyrazolam is a novel depressant substance of the benzodiazepine class.

Pyrazolam was originally developed at Hoffman-La Roche in the 1970s[2] and subsequently "rediscovered" and sold as a research chemical starting in 2012.[3]

Subjective effects include sedation, anxiety suppression, muscle relaxation, disinhibition, and euphoria. Pyrazolam is reported to produce comparably greater amounts of sedation and less euphoria than other benzodiazepines, limiting its recreational use.

It should be noted that the sudden discontinuation of benzodiazepines can be potentially dangerous or life-threatening for individuals using regularly for extended periods of time, sometimes resulting in seizures or death.[4] It is highly recommended to taper one's dose by gradually lowering the amount taken each day for a prolonged period of time instead of stopping abruptly.[5]

Benzodiazepines are habit-forming and can produce mental and physical dependence with continued use. It is strongly advised to use harm reduction practices if using this substance.

History and culture

This History and culture section is a stub. As a result, it may contain incomplete or wrong information. You can help by expanding it. |

Pyrazolam was originally developed by a team led by Leo Sternbach at Hoffman-La Roche in the 1970s[2] and subsequently "rediscovered" and sold as a research chemical starting in 2012.[3] The first official report of the drug came out of Finland in 2011 and another came from the UK in 2012.[6]

Chemistry

Pyrazolam is a drug of the benzodiazepine class. Benzodiazepine drugs contain a benzene ring fused to a diazepine ring, which is a seven membered ring with the two nitrogen constituents located at R1 and R4. Bromine is bound to this bicyclic structure at R7. Additionally, at R6 the bicylic core is substitued with a 2-pyridine ring. Pyrazolam also contains a 1-methylated triazole ring fused to and incorporating R1 and R2 of its diazepine ring. Pyrazolam belongs to a class of benzodiazepines containing this fused triazole ring, called triazolobenzodiazepines, distinguished by the suffix "-zolam".

Pharmacology

Benzodiazepines produce a variety of effects by binding to the benzodiazepine receptor site and magnifying the efficiency and effects of the neurotransmitter gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) by acting on its receptors.[7] As this site is the most prolific inhibitory receptor set within the brain, its modulation results in the sedating (or calming effects) of pyrazolam on the nervous system.

The anticonvulsant properties of benzodiazepines may be, in part or entirely, due to binding to voltage-dependent sodium channels rather than benzodiazepine receptors.[8]

Pyrazolam is most selective for the α2 and α3 receptor subtypes.[9] It is excreted by the body unchanged thus not interacting with liver enzymes like other benzodiazepines,[3] meaning that its use in people with reduced liver function may be safer.

Pyrazolam has structural similarities to alprazolam and bromazepam.[10] Unlike other benzodiazepines, pyrazolam does not appear to undergo metabolism, instead being excreted unchanged in the urine.[3] It is most selective for the α2 and α3 subtypes of the GABAA receptor.[11]

Subjective effects

Disclaimer: The effects listed below cite the Subjective Effect Index (SEI), an open research literature based on anecdotal user reports and the personal analyses of PsychonautWiki contributors. As a result, they should be viewed with a healthy degree of skepticism.

It is also worth noting that these effects will not necessarily occur in a predictable or reliable manner, although higher doses are more liable to induce the full spectrum of effects. Likewise, adverse effects become increasingly likely with higher doses and may include addiction, severe injury, or death ☠.

Physical effects

-

- Sedation - In terms of energy level alterations, pyrazolam is considerably less sedating than other substances of the same class unless it is taken at heavy doses.

- Dizziness

- Motor control loss

- Muscle relaxation

- Respiratory depression

Paradoxical effects

- Paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines such as increased seizures (in epileptics), aggression, increased anxiety, violent behavior, loss of impulse control, irritability and suicidal behavior sometimes occur (although they are rare in the general population, with an incidence rate below 1%).[12][13] These paradoxical effects occur with greater frequency in recreational abusers, individuals with mental disorders, children, and patients on high-dosage regimes.[14][15]

Cognitive effects

-

The cognitive effects of pyrazolam can be broken down into several components which progressively intensify proportional to dosage. The general head space of pyrazolam is described by many as one of mild sedation and proportionally intense anxiety suppression. It contains a large number of typical depressants cognitive effects.

The most prominent of these cognitive effects generally include:

- Amnesia

- Anxiety suppression

- Thought deceleration

- Analysis suppression

- Disinhibition

- Compulsive redosing

- Delusions of sobriety - This is the false belief that one is perfectly sober despite obvious evidence to the contrary such as severe cognitive impairment and an inability to fully communicate with others.

- Dream potentiation

Experience reports

There are currently no anecdotal reports which describe the effects of this compound within our experience index. Additional experience reports can be found here:

Toxicity and harm potential

|

This toxicity and harm potential section is a stub. As a result, it may contain incomplete or even dangerously wrong information! You can help by expanding upon or correcting it. |

Pyrazolam likely has a low toxicity relative to dose.[17] However, it is potentially lethal when mixed with depressants like alcohol or opioids.

It is strongly recommended that one use harm reduction practices when using this substance.

Tolerance and addiction potential

Pyrazolam is extremely physically and psychologically addictive.

Tolerance will develop to the sedative-hypnotic effects within a couple of days of continuous use. After cessation, the tolerance returns to baseline in 7 - 14 days. However, in certain cases this may take significantly longer in a manner which is proportional to the duration and intensity of one's long-term usage.

Withdrawal symptoms or rebound symptoms may occur after ceasing usage abruptly following a few weeks or longer of steady dosing, and may necessitate a gradual dose reduction. For more information on tapering from benzodiazepines in a controlled manner, please see this guide.

Benzodiazepine discontinuation is notoriously difficult; it is potentially life-threatening for individuals using regularly to discontinue use without tapering their dose over a period of weeks. There is an increased risk of hypertension, seizures, and death.[4] Drugs which lower the seizure threshold such as tramadol should be avoided during withdrawal.

Pyrazolam presents cross-tolerance with all benzodiazepines, meaning that after its consumption all benzodiazepines will have a reduced effect.

Overdose

Benzodiazepine overdose may occur when a benzodiazepine is taken in extremely heavy quantities or concurrently with other depressants. This is particularly dangerous with other GABAergic depressants such as barbiturates and alcohol since they work in a similar fashion, but bind to distinct allosteric sites on the GABAA receptor, thus their effects potentiate one another. Benzodiazepines increase the frequency in which the chlorine ion pore opens on the GABAA receptor while barbiturates increase the duration in which they are open, meaning when both are consumed, the ion pore will open more frequently and stay open longer[18]. Benzodiazepine overdose is a medical emergency that may lead to a coma, permanent brain injury or death if not treated promptly and properly.

Symptoms of a benzodiazepine overdose may include severe thought deceleration, slurred speech, confusion, delusions, respiratory depression, coma or death. Benzodiazepine overdoses may be treated effectively in a hospital environment, with generally favorable outcomes. Benzodiazepine overdoses are sometimes treated with flumazenil, a GABAA antagonist[19], however care is primarily supportive in nature.

Dangerous interactions

Although many drugs are safe on their own, they can become dangerous and even life-threatening when combined with other substances. The list below contains some common potentially dangerous combinations, but may not include all of them. Certain combinations may be safe in low doses of each but still increase the potential risk of death. Independent research should always be done to ensure that a combination of two or more substances is safe before consumption.

- Depressants (1,4-Butanediol, 2-methyl-2-butanol, alcohol, barbiturates, GHB/GBL, methaqualone, opioids) - This combination can result in dangerous or even fatal levels of respiratory depression. These substances potentiate the muscle relaxation, sedation and amnesia caused by one another and can lead to unexpected loss of consciousness at high doses. There is also an increased risk of vomiting during unconsciousness and death from the resulting suffocation. If this occurs, users should attempt to fall asleep in the recovery position or have a friend move them into it.

- Dissociatives - This combination can result in an increased risk of vomiting during unconsciousness and death from the resulting suffocation. If this occurs, users should attempt to fall asleep in the recovery position or have a friend move them into it.

- Stimulants - It is dangerous to combine benzodiazepines with stimulants due to the risk of excessive intoxication. Stimulants decrease the sedative effect of benzodiazepines, which is the main factor most people consider when determining their level of intoxication. Once the stimulant wears off, the effects of benzodiazepines will be significantly increased, leading to intensified disinhibition as well as other effects. If combined, one should strictly limit themselves to only dosing a certain amount of benzodiazepines per hour. This combination can also potentially result in severe dehydration if hydration is not monitored.

Legal status

Pyrazolam is not explicitly prohibited in most parts of the world, meaning it exists in a legal grey area. This means that it is not known to be specifically illegal, people may still be charged for its possession under certain circumstances such as under analogue laws and with intent to sell or consume.

- Canada: All benzodiazepines are listed in Schedule IV.[20]

- Germany: Pyrazolam is controlled under the NpSG (New Psychoactive Substances Act)[21] as of July 18, 2019.[22] Production and import with the aim to place it on the market, administration to another person and trading is punishable. Possession is illegal but not penalized.[23]

- Russia: Pyrazolam is a Schedule III controlled substance since 2017.[24]

- Sweden: Pyrazolam is a controlled substance.[25]

- Switzerland: Pyrazolam is a controlled substance specifically named under Verzeichnis E.[26]

- Turkey: Pyrazolam is a classed as drug and is illegal to possess, produce, supply, or import.[27]

- United Kingdom: Pyrazolam is a Class C controlled substance as of May 31, 2017. It is illegal to possess, produce or supply.[28]

See also

External links

References

- ↑ Risks of Combining Depressants - TripSit

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Sternbach, L. H., Walser, A., Preparation of triazolo benzodiazepines and novel compounds

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Moosmann, B., Hutter, M., Huppertz, L. M., Ferlaino, S., Redlingshöfer, L., Auwärter, V. (1 July 2013). "Characterization of the designer benzodiazepine pyrazolam and its detectability in human serum and urine". Forensic Toxicology. 31 (2): 263–271. doi:10.1007/s11419-013-0187-4. ISSN 1860-8973.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lann, M. A., Molina, D. K. (June 2009). "A fatal case of benzodiazepine withdrawal". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 30 (2): 177–179. doi:10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181875aa0. ISSN 1533-404X.

- ↑ Kahan, M., Wilson, L., Mailis-Gagnon, A., Srivastava, A. (November 2011). "Canadian guideline for safe and effective use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain. Appendix B-6: Benzodiazepine Tapering". Canadian Family Physician. 57 (11): 1269–1276. ISSN 0008-350X.

- ↑ O’Connor, L. C., Torrance, H. J., McKeown, D. A. (March 2016). "ELISA Detection of Phenazepam, Etizolam, Pyrazolam, Flubromazepam, Diclazepam and Delorazepam in Blood Using Immunalysis ® Benzodiazepine Kit". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 40 (2): 159–161. doi:10.1093/jat/bkv122. ISSN 0146-4760.

- ↑ Haefely, W. (29 June 1984). "Benzodiazepine interactions with GABA receptors". Neuroscience Letters. 47 (3): 201–206. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(84)90514-7. ISSN 0304-3940.

- ↑ McLean, M. J., Macdonald, R. L. (February 1988). "Benzodiazepines, but not beta carbolines, limit high frequency repetitive firing of action potentials of spinal cord neurons in cell culture". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 244 (2): 789–795. ISSN 0022-3565.

- ↑ Hester, J. B., Von Voigtlander, P. (November 1979). "6-Aryl-4H-s-triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]benzodiazepines. Influence of 1-substitution on pharmacological activity". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 22 (11): 1390–1398. doi:10.1021/jm00197a021. ISSN 0022-2623.

- ↑ Hester, J. B., Rudzik, A. D., Kamdar, B. V. (November 1971). "6-phenyl-4H-s-triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]benzodiazepines which have central nervous system depressant activity". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 14 (11): 1078–1081. doi:10.1021/jm00293a015. ISSN 0022-2623.

- ↑ Hester, J. B., Von Voigtlander, P. (November 1979). "6-Aryl-4H-s-triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]benzodiazepines. Influence of 1-substitution on pharmacological activity". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 22 (11): 1390–1398. doi:10.1021/jm00197a021. ISSN 0022-2623.

- ↑ Saïas, T., Gallarda, T. (September 2008). "[Paradoxical aggressive reactions to benzodiazepine use: a review]". L’Encephale. 34 (4): 330–336. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2007.05.005. ISSN 0013-7006.

- ↑ Paton, C. (December 2002). "Benzodiazepines and disinhibition: a review". Psychiatric Bulletin. 26 (12): 460–462. doi:10.1192/pb.26.12.460. ISSN 0955-6036.

- ↑ Bond, A. J. (1 January 1998). "Drug- Induced Behavioural Disinhibition". CNS Drugs. 9 (1): 41–57. doi:10.2165/00023210-199809010-00005. ISSN 1179-1934.

- ↑ Drummer, O. H. (February 2002). "Benzodiazepines - Effects on Human Performance and Behavior". Forensic Science Review. 14 (1–2): 1–14. ISSN 1042-7201.

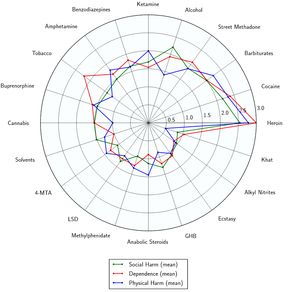

- ↑ Nutt, D., King, L. A., Saulsbury, W., Blakemore, C. (24 March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. ISSN 0140-6736.

- ↑ Mandrioli, R., Mercolini, L., Raggi, M. A. (October 2008). "Benzodiazepine metabolism: an analytical perspective". Current Drug Metabolism. 9 (8): 827–844. doi:10.2174/138920008786049258. ISSN 1389-2002.

- ↑ Twyman, R. E., Rogers, C. J., Macdonald, R. L. (March 1989). "Differential regulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor channels by diazepam and phenobarbital". Annals of Neurology. 25 (3): 213–220. doi:10.1002/ana.410250302. ISSN 0364-5134.

- ↑ Hoffman, E. J., Warren, E. W. (September 1993). "Flumazenil: a benzodiazepine antagonist". Clinical Pharmacy. 12 (9): 641–656; quiz 699–701. ISSN 0278-2677.

- ↑ New item… Branch, L. S. (2022), Consolidated federal laws of Canada, Controlled Drugs and Substances Act

- ↑ "Anlage NpSG" (in German). Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ↑ "Verordnung zur Änderung der Anlage des Neue-psychoaktive-Stoffe-Gesetzes und von Anlagen des Betäubungsmittelgesetzes" (PDF). Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2019 Teil I Nr. 27 (in German). Bundesanzeiger Verlag. July 17, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ↑ "§ 4 NpSG" (in German). Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ↑ Постановление Правительства РФ от 12.07.2017 N 827 “О внесении изменений в некоторые акты Правительства Российской Федерации в связи с совершенствованием контроля за оборотом наркотических средств и психотропных веществ” - КонсультантПлюс

- ↑ Regeringskansliets rättsdatabaser

- ↑ "Verordnung des EDI über die Verzeichnisse der Betäubungsmittel, psychotropen Stoffe, Vorläuferstoffe und Hilfschemikalien" (in German). Bundeskanzlei [Federal Chancellery of Switzerland]. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ↑ https://resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2017/01/20170112-8.pdf

- ↑ The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order 2017